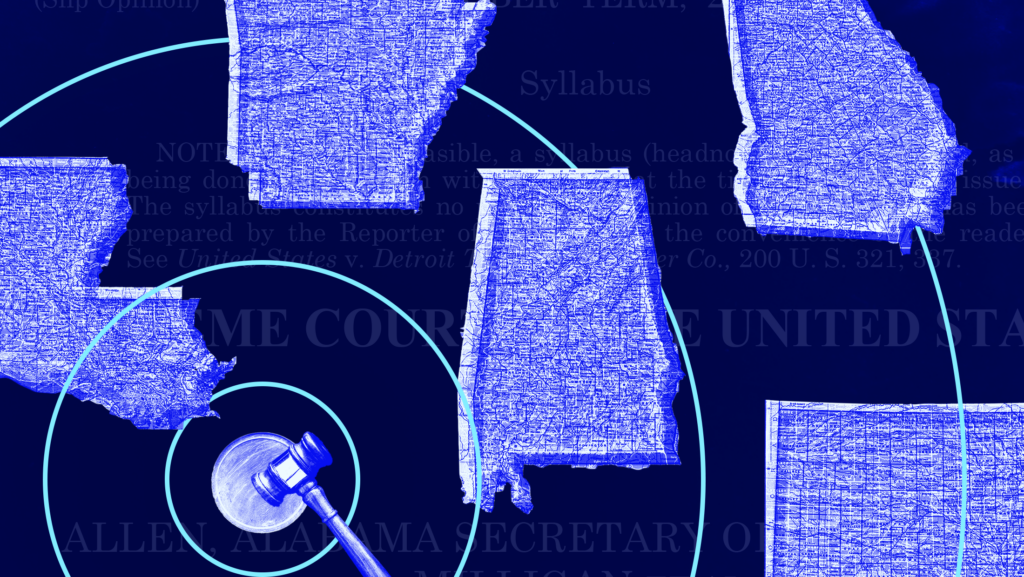

Two Weeks Later, Allen v. Milligan Has Impacted These States

Two weeks ago today, the U.S. Supreme Court dropped a major voting rights win. In Allen v. Milligan, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote a majority opinion striking down Alabama’s congressional map for violating Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). In doing so, the Court affirmed the current application of Section 2, a portion of the landmark law that bans voting rules or electoral schemes that dilute the voting strength of minority voters.

While voting rights advocates braced for the worst — a weakening of a crucial, highly litigated section of the VRA — that blow never came. The opinion, released on June 8, 2023, sends a powerful signal for the continued application of Section 2 despite cynical attempts by the state of Alabama to have the court “rewrite the law.”

The consequences were immediate: Within hours and days, previously stalled cases across the country started moving again. Here’s what has happened in the two weeks since the decision.

This summer, the Alabama Legislature will redraw a new congressional map with a second district where Black voters can elect a candidate of their choice.

The Allen case emerged out of Alabama following the enactment of new redistricting maps drawn with 2020 census data. In January 2022, a panel of three federal judges determined that Alabama’s congressional map likely violated Section 2 of the VRA. The court ordered the Legislature to redraw a map that has two, rather than one, majority-Black districts.

Instead of following the court order, the state of Alabama accelerated the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which paused the lower court’s order via its shadow docket. This meant that Alabama’s likely illegal map was used during the 2022 midterm elections.

A year and a half later, the Supreme Court released its full opinion in the case, with the Court agreeing with the three-judge panel’s decision from January 2022. Roberts emphasized: “We see no reason to disturb the District Court’s careful factual findings.”

Just days later, on June 12, the Court unpaused its shadow docket order, allowing the lower court’s order to go back into effect. The Alabama Legislature is once again ordered to redraw a map with fairer districts.

Alabama officials then filed paperwork indicating their intention to enact a new congressional map by July 21. The lower court agreed upon the timeline, giving the Legislature until that date to pass a new map that incorporates a second majority-Black district. As part of this timeline, the court ordered Alabama lawmakers to provide status updates on July 7 and 14. Since the Legislature is not currently in session, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey (R) will have to call a special session for lawmakers to draw the new map.

In addition to the state’s congressional map, Alabama’s state House and state Senate districts will likely be improved. Just over 24 hours after the Allen opinion dropped, a federal court unpaused a lawsuit challenging Alabama’s state legislative maps for discriminating against Black voters. The case was previously paused until there was a decision in Allen.

The most immediate impact will be felt in Louisiana, where a case was paused pending Allen given the similar facts.

The case most closely tied to Allen is Ardoin v. Robinson, a Section 2 lawsuit that challenges Louisiana’s congressional map, also drawn with 2020 census data. If Alabama must redraw a map with another district giving electoral opportunity to Black voters, Louisiana will have to do the same.

Last June, the Supreme Court paused the Louisiana case pending a decision in Allen. A lower court had similarly found that Louisania likely violated Section 2 of the VRA but because the Supreme Court paused the decision, Louisianans voted under that map in 2022.

Litigation over Louisiana’s congressional map should now resume. Just hours after Allen was issued, the state of Louisiana sent a letter to the Supreme Court in an attempt to distinguish the case from Allen and have the Court hear the case separately.

Lawyers representing the pro-voting groups and Black voters in Ardoin called out Louisiana officials for their attempt to separate their case from a decision they disliked. In “an immediate about-face” and “transparent bait-and-switch,” Louisiana is now trying to assert that its case is meaningfully different from the Alabama case.

After receiving Louisiana’s latest attempt to keep an unfair map in place, the Court should soon issue its order unpausing the case. It is expected that the Louisiana Legislature will then have to draw a fairer congressional map for Black voters.

Like Alabama, the Louisiana Legislature is not in session at the moment, but Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) seems eager for his state to pass an improved map. “As I said when I vetoed it, Louisiana’s current congressional map violates the Voting Rights Act,” Edwards, a Democrat whose veto was overridden by the Legislature, wrote when Allen came down. “Louisiana can and should have a congressional map where two of our six districts are majority Black. Today’s decision reaffirms that.”

“[The Allen ruling] will undoubtedly have the same effect in Louisiana. But this decision will likely reverberate even further down the political spectrum,” Louisiana Progress Executive Director Peter Robins-Brown recently wrote for Democracy Docket, citing a lawsuit challenging Louisiana’s state legislative maps that was also paused. “But lawyers in that case have already filed to have that pause lifted. Even local maps, like those adopted for school boards in East Baton Rouge and Jefferson parishes, could end up being redrawn.”

Georgia was directly impacted by the Supreme Court’s 2022 shadow docket decisions, and several Section 2 cases are gearing up again.

The Peach State is the third Southern state most directly impacted by Allen. Ahead of the 2022 midterms, a judge in Georgia noted that the state’s congressional and legislative maps likely violated Section 2 of the VRA. However, the judge allowed Georgians to vote under those maps, citing the Supreme Court’s shadow docket order involving the Alabama map, which suggested that it was too close to an election to alter the map.

On the same day that the Supreme Court released Allen, Georgia court activity immediately picked up again. The federal judge in the case challenging Georgia’s redistricting maps requested additional briefings from parties in light of the Allen decision.

Additionally, in a separate lawsuit challenging Georgia’s election system for public service commissioners, plaintiffs filed a notice that the Supreme Court’s decision bolsters their argument that Georgia’s public service commission elections are unfair.

The Allen opinion undercuts a nefarious right-wing legal argument.

Over the past few months, a legal argument has gained traction in conservative circles: a theory that key voting rights protections are not privately enforceable, meaning that individuals and organizations do not have the ability to bring lawsuits under a given provision. This long-standing legal concept is known as a private right of action.

Without a private right of action, only the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) could file a lawsuit under a federal statute, making it largely unenforceable. The vast majority of cases safeguarding the right to vote today come from individuals, civil rights organizations or political parties and affiliated groups — and not the DOJ.

The most outlandish application of this no-private-right-of-action argument involves Section 2 of the VRA in a legislative redistricting case in Arkansas. In February 2022, a federal district court judge rejected decades of precedent to rule that there is no private right of action under Section 2, a decision that is now on appeal before the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

While Roberts did not explicitly address the private right of action under Section 2 in his opinion, the mere fact that he decided Allen — a case brought by private litigants — appeared to reaffirm it. The DOJ already agrees: On June 9, the DOJ submitted a brief to the 8th Circuit arguing that the decision in Allen “supports the conclusion that Section 2…contains an implied private right of action.”

In a city-level lawsuit in Kansas, plaintiffs similarly submitted a notice to the court asserting that the Allen ruling further exemplified the fact that private litigants can file lawsuits under Section 2 of the VRA. While far-right lawyers might continue to make this unfounded argument — and cite a footnote from Justice Clarence Thomas’ dissent — Allen should help put it to rest.

The impacts of Allen will continue to cascade across the country.

Currently, there are 32 active Section 2 lawsuits across 10 states. This includes Arkansas, where a group of voters are attempting to revive a challenge to the state’s congressional map that was dismissed in May. Last week, the voters asked the Supreme Court to review the lawsuit, the first case with Section 2 claims to be appealed to the Court since its Allen ruling.

In Texas, litigation is stalled because of discovery issues, but numerous U.S. House and state legislative districts will be implicated.

“Maybe most importantly,” Robins-Brown emphasized, “the Allen decision maintains a sense that the people still have an outlet in this country to challenge injustice. That outlet is messy and imperfect and aggravating and long and winding and it often doesn’t even lead to a just outcome. But it can work sometimes.”

As the flurry of activity within the first two weeks since the Supreme Court’s major ruling indicates, that outlet is once again open: The Allen decision will take a central role in ensuring voters can continue to fight for fair maps.