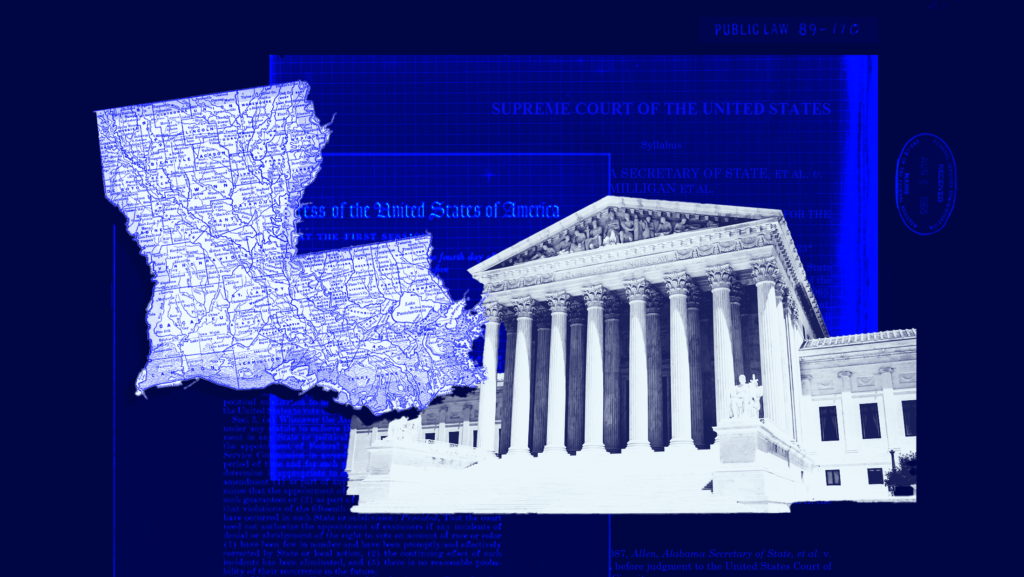

Louisiana Gets a Shot at Fair Maps After Supreme Court Ruling in Allen v. Milligan

Most people who work on, or follow, civil rights issues in the U.S. woke up on Thursday, June 8, 2023, with a feeling of impending doom. That morning, the U.S. Supreme Court was expected to announce its ruling in the Allen v. Milligan case, which derived from a lawsuit challenging Alabama’s congressional map for diluting the voting power of Black voters in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), the law’s most critical remaining provision. The Court’s decision would determine whether the VRA, one of the most important laws in U.S. history, remained in place in any meaningful form. Few, if any, thought it would survive.

Chief Justice John Roberts has spent much of his career stripping the VRA piece by piece, including authoring the decade-old ruling in the Shelby County v. Holder case that gutted Section 5 of the VRA. Section 5 had required certain states, counties and cities with a history of racist gerrymandering and political disenfranchisement to get “preclearance” from the Department of Justice before enacting new political maps.

Given Roberts’ history with the VRA, the conservative makeup of the Court and the Court’s “shadow docket” ruling in the Allen case 11 months prior that paused a lower court’s opinion that blocked the map for likely violating the VRA, it seemed inevitable that a majority of the justices would use this opportunity to fully dismantle the VRA. That type of ruling would leave voters from racial minority groups with essentially no legal recourse to challenge racially discriminatory political maps. As I previously described on Democracy Docket, this case was an opportunity that conservative lawyers, activists and elected officials across the country, including many in my home state of Louisiana, have been working toward for years.

Maybe most importantly, the Allen decision maintains a sense that the people still have an outlet in this country to challenge injustice.

Then something nearly unimaginable happened. In a 5-4 decision, with Roberts writing for the majority, the Court ruled in favor of Milligan and against the state of Alabama, upholding Section 2 of the VRA. That decision will likely have major implications for other states, including Georgia and Texas, but most immediately it will impact Louisiana, where a similar case, Robinson v. Ardoin, was on hold at the Supreme Court, awaiting the ruling in Allen.

Going by the math, Louisiana’s case is even stronger than Alabama’s, so Thursday’s ruling, which will require the creation of another majority-minority congressional district in Alabama, will undoubtedly have the same effect in Louisiana. But this decision will likely reverberate even further down the political spectrum.

A lawsuit alleging that Louisiana’s state legislative maps also violate Section 2, Nairne v. Ardoin, has been paused for months. But lawyers in that case have already filed to have that pause lifted. Even local maps, like those adopted for school boards in East Baton Rouge and Jefferson parishes, could end up being redrawn.

While those legal battles will play out in the weeks and months to come, and it’s impossible to predict their outcomes, it appears likely that some of the historical wrongs that are embedded in Louisiana’s current maps and long history of racially motivated political disenfranchisement will be redressed to some degree through those upcoming legal proceedings. Those proceedings will also, hopefully, provide some amount of validation to those of us — citizens, advocates and legal experts — who went to special redistricting sessions and meetings at the state capitol and in local councils to argue that what Republican elected officials were doing was unconstitutional.

Maybe most importantly, the Allen decision maintains a sense that the people still have an outlet in this country to challenge injustice. That outlet is messy and imperfect and aggravating and long and winding and it often doesn’t even lead to a just outcome. But it can work sometimes. And we all need to be reassured that there are still norms in this country, that the rule of law can still be applied in an even-handed manner and that outright oppression and suppression can be successfully challenged.

At the same time, this ruling didn’t address some deep, persistent systemic problems with our democracy. As Roberts noted in his opinion, even under the current law that he and his colleagues protected, Section 2 lawsuits have “rarely been successful.” Section 5, the old preclearance standard, is still extinct. State and local governments across the country, but especially in the South, continue to pass laws and enact policies and procedures that directly or indirectly limit racial minority groups from fully participating in the political process.

The Allen decision will probably go down as one of the more historic rulings of Roberts’ tenure as chief justice. Its impact will reshape political maps in several states and, very likely, the entire country, since redrawing the relevant congressional maps could lead to a change in which party holds the majority in Congress. It also offers an incalculable sense of relief to the many millions of Americans who have lost, or were starting to lose, their faith in the country’s legal system.

There is still a long way to go on the road to true justice in this country. Thankfully, we took one major step along that road with this ruling. That favorable outcome was the result of exceptional advocacy by everyday citizens, hard-working organizers and talented attorneys. Every other major step toward justice will take that same type of partnership and effort. But the Allen decision shows us that if we fight, and if we work together, we can win.

Peter Robins-Brown is the executive director of Louisiana Progress.