The Conservative Legal Movement’s Latest Target

On Monday, March 6, a voting rights case out of Texas will head to court in the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Vote.org, the nation’s largest voter registration nonprofit, brought the lawsuit but won’t be the only group in the courtroom — the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) will participate as well.

“The United States has a strong interest in the resolution of this appeal and believes that its participation in oral argument will be helpful to the Court,” the Civil Rights Division of the DOJ recently wrote. But why is the U.S. government so invested in the outcome of a case challenging a technical element of Texas’ voter registration policy? It has to do with what Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R) is arguing before the court: a key voting rights protection is not privately enforceable, meaning that individuals and organizations, like Vote.org, do not have the ability to bring lawsuits under this provision.

This legal concept is known as a private right of action or a private cause of action. Without it, only the DOJ — as opposed to individuals or groups, too — can file a lawsuit under a statute, making the given statute largely unenforceable. The vast majority of cases safeguarding the right to vote today come from individuals, political parties and their affiliated groups or civil rights organizations.

Paxton is not the only actor in the conservative legal movement making this argument, which, if adopted by courts, would severely undercut the efficacy of numerous federal laws. In the Vote.org case and elsewhere, the latest target is a little known section of the Civil Rights Act of 1964: the Materiality Provision, which protects voters from disenfranchisement on the basis of “an error or omission…if such error or omission is not material in determining whether such individual is qualified.” In other words, federal law ensures that voters aren’t disqualified because of trivial mistakes.

There are multiple ongoing efforts to undermine the Materiality Provision, but simmering under the surface is an attempt to push this no-private-right-of-action argument onto other federal voting rights statutes, including a central tenet of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA). If courts embrace this theory — one largely unmoored from history and precedent — then the power of voting protections would be greatly diminished.

“Voting rights laws could become a dead letter:” The importance of private enforcement.

The DOJ has limited time and resources; lawsuits by private parties have long been essential in advancing civil and voting rights. Daniel Tokaji, dean of the University of Wisconsin Law School, told Democracy Docket that he was glad that the DOJ was supporting a private right of action: “If there’s no private right of action, then the only means of enforcement is for DOJ to sue,” he continued. “That means that civil and voting rights laws could become a dead letter under an administration that is unfriendly to their aims.”

During the four years under former President Donald Trump, the DOJ only brought a single case under Section 2 of the VRA, a suit dealing with the election methods in a South Dakota school district. But even in an administration predisposed to supporting voting rights, the DOJ is far from the most litigious actor around. Under current U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland, the DOJ has filed two VRA redistricting lawsuits since the release of 2020 census data. In contrast, there have been 31 VRA redistricting lawsuits brought by private litigants.

A Trump-appointed federal judge might put the landmark VRA at risk.

The most outlandish place where the legal theory over private enforcement has emerged is in a redistricting case in Arkansas. In February 2022, a federal district court judge rejected decades of precedent to rule that there is no private right of action under Section 2 of the VRA, a decision that is now on appeal before the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Section 2 prohibits any voting law that intends or results in a “denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

Instead of considering the substance of the lawsuit brought by the Arkansas NAACP, Trump-appointed Judge Lee Rudofsky ruled that nobody except the U.S. attorney general can bring such a lawsuit. (The DOJ unequivocally disagreed with this interpretation while declining to join the case.)

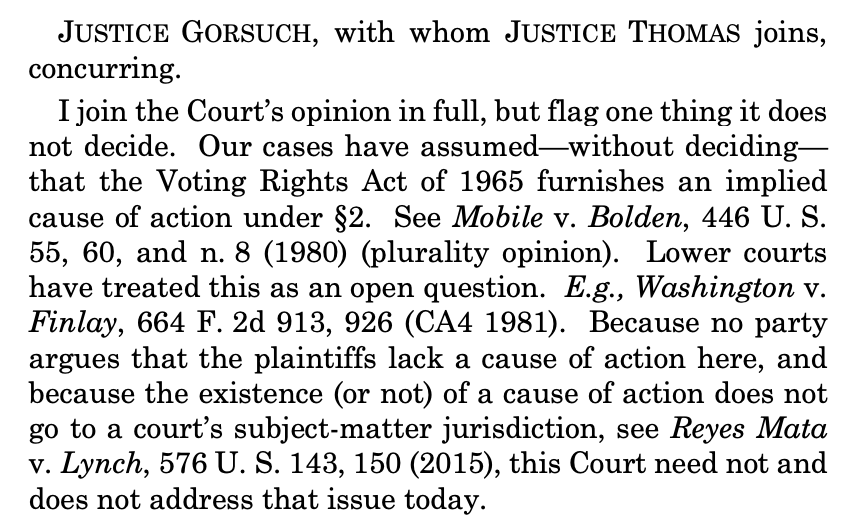

Although Rudofsky’s assertion seems counter to legal history, we know he may have at least two supporters on the nation’s highest court. Rudofsky based the central portion of his order on a single concurring paragraph in the 2021 U.S. Supreme Court case Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee. Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, wrote a concurrence to highlight the fact that the case “assumed—without deciding” that the VRA has an implied private right of action.

Though Gorsuch asserted that the private right of action under Section 2 is an “open question,” it was answered years ago. In the 1969 case Allen v. State Board of Elections, the Supreme Court confirmed that private litigants can bring suits under Section 5 of the VRA: “The achievement of the Act’s laudable goal could be severely hampered, however, if each citizen were required to depend solely on litigation instituted at the discretion of the Attorney General.”

Three decades later in Morse v. Republican Party of Virginia (1996), the Supreme Court extended that logic to another section of the VRA, and in doing so, specifically noted the existence of a private right of action under Section 2. “Although [Section] 2, like [Section] 5, provides no right to sue on its face, ‘the existence of the private right of action under Section 2…has been clearly intended by Congress since 1965,’” the majority opinion wrote. Thomas is the only justice who weighed in on this 1996 case and remains on the bench today; he dissented.

In disregarding this precedent, Rudofsky asserted in the Arkansas redistricting lawsuit that “Allen has been relegated to the dustbin of history” and noted that Allen and Morse deal with other sections of the VRA and thus “cannot be stretched any further.” Rudofsky instead relied on a 2001 case where the Court held that there was no private right of action under a specific civil rights statute. In general, the Supreme Court has moved towards stricter interpretation for determining whether federal statutes authorize a private right of action since the turn of the century, though all outside of the election context.

Nonetheless, in an amicus brief, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law explained how Rudofsky incorrectly applied the 2001 case. The brief emphasized: “In the fifty-seven years since the passage of the Voting Rights Act, hundreds of courts around the country—including the United States Supreme Court and [the 8th Circuit]—have presided over Section 2 cases brought by private litigants without a whisper that there was no private right of action.”

The Materiality Provision remains the most likely vessel for undermining the private right of action.

If the 8th Circuit affirms Rudofsky’s decision regarding the VRA, it would radically upend the landmark law. However, the Materiality Provision of the Civil Rights Act remains even more vulnerable to the private enforcement argument than Section 2.

In the Civil Rights Act, the law explicitly authorizes the U.S. attorney general to bring litigation to enforce its voting rights provisions, but it is silent on whether an individual or organization may do so as well. The Supreme Court has never ruled on this question under the Materiality Provision.

There is also a circuit court split: The 3rd and 11th U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals agree that there is a private right of action under this provision, while the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has held several times that the Materiality Provision does not allow private individuals or groups to bring lawsuits. (In the absence of a definitive Supreme Court stance, federal circuit courts help establish the prevailing legal understanding.) Given the differing circuit court rulings, it would not be surprising if the Supreme Court takes up this issue in the near future to resolve the disagreement, though the Court declined to do so just a few years ago.

A general increase in election-related litigation over the past decade, including cases invoking the Materiality Provision, has made resolving this question even more pressing. In a 2010 law review article, Tokaji noted that the “problem is that existing private-right-of-action doctrine fails to account for the vital role that federal courts play in overseeing elections in the United States, especially through pre-election litigation,” which has swelled in recent years.

In addition to the Texas voter registration case before the 5th Circuit, Pennsylvania provides the next most fertile ground for the conservative argument. Last year, there were a series of interconnected lawsuits in the Keystone State centering on whether election officials should count mail-in ballots that are missing a date on the outside envelope but are otherwise valid. Democratic Party-affiliated groups and civil rights organizations argued that discarding these ballots would violate the Materiality Provision.

In May 2022, the 3rd Circuit ruled that officials must count undated mail-in ballots and, in doing so, affirmed a private right of action under the Materiality Provision. One month before the 2022 midterms, the Supreme Court voided this decision, meaning that it is no longer binding, though it may remain highly persuasive. This triggered a fresh wave of lawsuits in federal court.

The Republican National Committee, National Republican Congressional Committee and Republican Party of Pennsylvania intervened in the lawsuits and pushed the argument, among others, that the claims should be dismissed because the statute does not grant the groups challenging the practice “a right to sue.” The DOJ, once again, submitted a statement refuting this argument.

Instead of winning cases on the merits, right-wing election lawyers are trying to ensure that pro-voting organizations and voters themselves can’t bring lawsuits in the first place. It’s unclear whether a majority of the current Supreme Court justices would be receptive to such an argument — nonetheless, the conservative legal movement seems to be counting on it.