Three Things To Watch During the Supreme Court’s Argument on Trump’s Immunity

The U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments this week on whether former President Donald Trump is absolutely immune from criminal prosecution over acts that allegedly happened when he was president, in a case that could have grave implications both for the presidency and Trump’s legal fights.

At issue is a federal criminal indictment against Trump in connection with he and his allies’ alleged efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election, a scheme that culminated in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol by a mob of Trump supporters.

As Trump battles this case and several others, his lawyers have asked the high court to determine whether presidential immunity will shield Trump from criminal liability now that he’s no longer in office. Trump has repeatedly claimed, both through his lawyers and himself, that a president must have full immunity in order to avoid politically-motivated prosecutions — an assertion that may energize his supporters, but has been roundly rejected by the courts.

In December, the federal judge overseeing the case denied Trump’s immunity claims, stating in her opinion that former presidents “enjoy no special conditions on their federal criminal liability.” In upholding that opinion, a federal appeals court held that “any executive immunity that may have protected him while he served as President no longer protects him against this prosecution.”

Now, the nation’s high court is poised to rule on a question it has yet to definitively answer. Here are three things to watch for as oral argument gets underway.

Should Trump be immune from criminal prosecution?

At the hearing, Trump’s lawyers will likely expound on the arguments in their petition submitted to the Court. Among their core arguments is that the U.S. Constitution only gives Congress — not the courts — the authority to sit in judgment over his official acts.

In other words, Trump argues that only Congress is legally able to convict him through the impeachment process, which Trump has undergone two times and in both instances was impeached by the House but not the Senate, meaning he was not convicted by the full Congress.

Trump’s lawyers have cited the Impeachment Judgment Clause as the foundation for their claims, according to their brief, which states that the Constitution confirms that “current and former Presidents are immune from criminal prosecution for official acts.”

Their case also relies heavily on Nixon v. Fitzgerald, the Supreme Court decision that held that the president is entitled to immunity from civil liability, so that the presidency would not be hampered by the threat of legal action after a president’s tenure. Establishing criminal immunity as part of that protection, the Trump brief states, would align with the 1982 ruling.

“[U.S. District] Judge [Tanya] Chutkan said it best in her order,” said former U.S. Attorney in Alabama Joyce Vance, paraphrasing Chutkan’s opinion. “She said, it may not be such a terrible thing – when a sitting president is making a decision – to have him thinking, ‘I shouldn’t violate the criminal laws of the United States because I might get prosecuted.’ That’s one of the primary reasons that we have criminal laws, to engage in deterrence.”

While Trump’s critics have disputed the former president’s claims of sweeping immunity from potentially criminal conduct, some Republicans have expressed their support.

U.S. Sen. Steve Daines, a Montana Republican, and the National Republican Senatorial Committee argued in an amicus brief that the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, in rejecting Trump’s claims, “has now shielded Presidents from the lesser danger” of civil liability, “while exposing them to the greater,” threat of criminal prosecution.

In a separate brief supporting Trump, Alabama’s attorney general and over a dozen other Republican states questioned whether the prosecution of Trump is politically-driven, and further argued that the D.C. Circuit did not sufficiently consider the risk of partisan prosecution into its analysis of Trump’s immunity claims.

“Our criminal justice system does not depend on the whims of prosecutors,” Vance told Democracy Docket in a phone interview. “And the risk that a president or anyone else would be prosecuted purely out of spite on the part of prosecutors is belied by all of the procedural protections that are in place,” she said.

How will the outcome of this argument impact Trump’s broader legal fights?

One fact on which Republicans and Democrats seem to agree: the stakes of this case are considerably high.

A ruling that affirms Trump’s claims “would upset the separation of powers and usher in a regime that would have been anathema to the Framers,” Jack Smith, special counsel for the U.S. Department of Justice, who’s leading the federal case, asserted in his response to Trump’s petition.

“No case supports former President Trump’s dangerous argument for federal criminal immunity,” states an opposing brief co-authored by J. Michael Luttig, a former appeals court judge who made headlines for his searing 2022 testimony at the Jan. 6 House committee hearings.

A decision against Trump doesn’t guarantee that he would stand trial before the 2024 presidential election — and it might not matter much if Trump wins the presidency in November.

“It seems almost definitely the case that Trump couldn’t be tried, convicted and sentenced [before the election],” Thomas Keck, a political science professor at Syracuse University, told Democracy Docket in a phone interview, noting that the Court could take months to rule. “If he wins, and is inaugurated in January, then he can make the whole thing go away,” he said, referring to a president’s authority to pardon himself and others of crimes.

Trump is facing four indictments, including a New York state case charging him with falsifying business records that went to trial this week. On the first day of trial, the judge presiding over the case denied a request from Trump to be excused from next week’s proceedings so that he can attend oral arguments in the immunity case, news outlets covering the trial reported.

While Trump faces allegations of election interference in the Georgia case against him, Smith’s indictment took direct aim at Trump’s alleged role in “exploiting the violence and chaos that transpired at the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021,” per Smith’s brief.

“Were [Trump] to not be held responsible for that, it leaves him free to try again,” Keck said. “And it’s a signal to anybody else who might be inclined to try it.”

How will the Court respond to the parties’ arguments?

The question both sides will argue — “whether and if so to what extent does a former President enjoy presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for conduct alleged to involve official acts during his tenure in office” — was constructed by the Court, not either party.

Former New York prosecutor Bennett Gershman told Salon that the Court would need to take the “narrowest possible approach” to that question. A broad approach, he said, would require the Court to render a decision that could have “terrifying implications.”

Vance noted that the Court could determine whether a limited scope of immunity applies to a former president, “but you don’t need to define that to decide this case,” she told Democracy Docket, “because whether there is immunity in some other areas, there is not immunity for a president who tries to steal an election.”

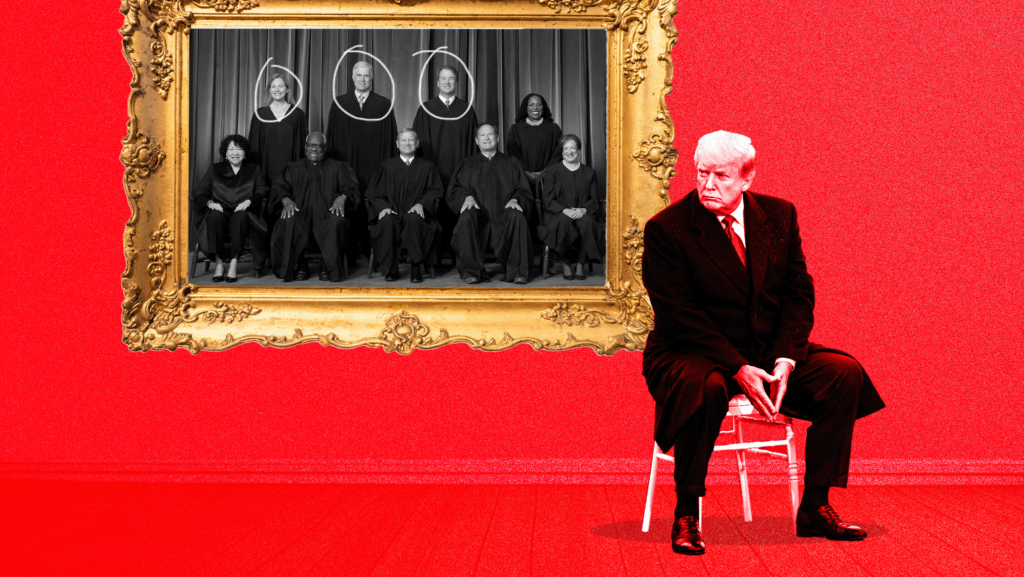

Though conservatives dominate the Supreme Court, that doesn’t mean they’re certain or likely to side with Trump, as demonstrated by previous rulings that clashed with Trump’s interests.

A 2020 ruling in Trump v. Vance, for example, rejected Trump’s attempt to quash a grand jury subpoena from then-Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. (D) as part of a probe into Trump’s finances while he was in office.

The 7-2 ruling was backed by Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch, both Trump appointees, with fellow conservative Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito dissenting.

Notably, Alito in his dissenting opinion seemed skeptical of the notion that a sitting president can be subpoenaed in a criminal case. How his thinking might apply to the current case, which focuses less on what can happen to a president while in office and more on what can happen to him afterward, remains to be seen.

“It is not enough to recite sayings like ‘no man is above the law’ and ‘the public has a right to every man’s evidence,’” Alito wrote. “The law applies equally to all persons, including a person who happens for a period of time to occupy the Presidency. But there is no question that the nature of the office demands in some in-stances that the application of laws be adjusted at least until the person’s term in office ends.”