Where Are the Judges Who Know How To Fight for Workers?

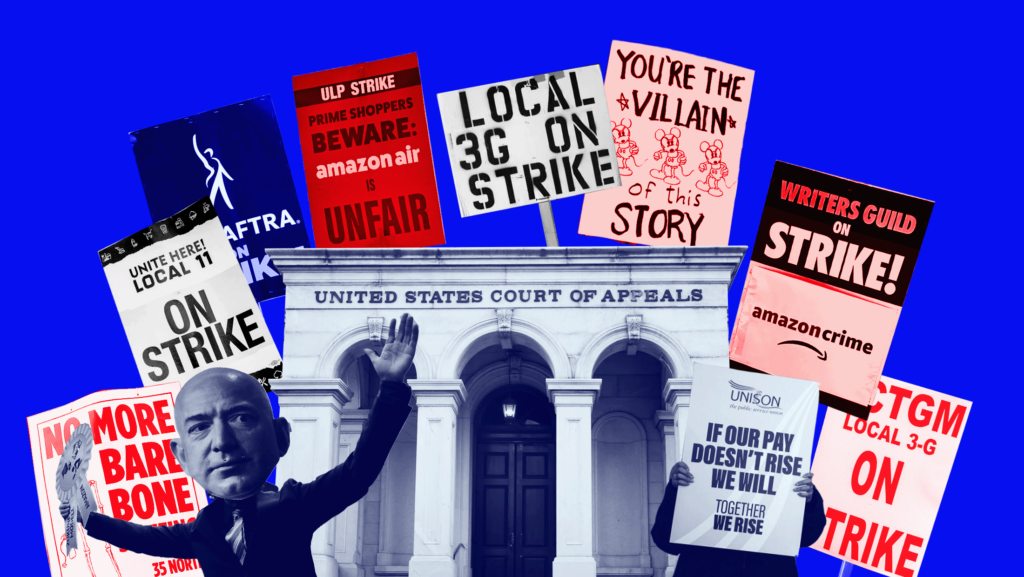

It’s a boom time for unions. Last year alone, we witnessed incredible bravery from auto workers, hotel workers, writers and actors and Amazon employees. More and more workers are organizing and taking to the picket line to demand better from their employers. It’s awe-inspiring.

Yet, workers deserve more than public support for their struggle for just wages and working conditions; they also deserve the confirmation of judges who will hear (and truly understand) their claims.

This year, the Senate has the chance to put exactly that kind of attorney on the bench in Nicole Berner. Berner has spent nearly two decades at SEIU, one of the nation’s largest unions, including serving as its general counsel since 2017. She has been the epitome of an advocate for workers, litigating cases under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, and the Fair Labor Standards Act, as well as constitutional claims, to fight for fair workplace protections. In sum, she’s a champion for the middle class. What could be more crucial when the chasm between rich and poor is growing and the life prospects of working people are declining?

Sadly, nominees like Berner are few and far between. An Alliance for Justice report from 2022 examining the nation’s circuit courts found that 68% of appellate judges were former corporate attorneys and 28% were former prosecutors. By contrast, just 6% of the federal judiciary was made up of what we called “economic justice” judges. This broad category included judges who dedicated their careers to union-side labor law, employee-side wage and hour law, consumer protections and civil legal aid. Union-side lawyers like Berner are especially rare.

When our judges are more familiar with our experiences — whether through advocating for us or through their own similar experiences — that wisdom transforms the justice they dispense.

In the year and a half since that report came out, very little has changed. The Senate has confirmed only one new circuit court judge with notable economic justice experience, Rachel Bloomekatz (confirmed to the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals last July) — not enough to shift the percentage. There have also only been a few district court nominees with this legal background, such as Casey Pitts, confirmed to the Northern District of California last June, and Mustafa Kasubhai, whose nomination to the District of Oregon is still pending before the Senate.

The consequences of not having economic justice judges are plainly disastrous for the American public. Judicial decisions undermining COVID safety protections and eviction protections have harmed tens of millions.

Then of course there are the decisions that harm the ability of unions to recruit workers and resist intransigent managers. Consider that since former President Donald Trump started appointing judges and justices, there have been three major anti-union Supreme Court decisions. Janus v. AFSCME, decided just after Justice Neil Gorsuch joined the Court in 2018, made it harder for unions to collect fees from the non-members they nevertheless represent. Then in 2021, Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid severely restricted union organizing, particularly for farm works.

In last year’s Glacier Northwest v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the Supreme Court further weakened union protections by subjecting union organizers to liability for alleged destruction of property — undermining the authority of the agency created under the NLRA to govern such decisions. Only Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, the Court’s lone public defender, declared how noxious the decision was to working people. “Workers are not indentured servants, bound to continue laboring until any planned work stoppage would be as painless as possible for their master,” she wrote. “They are employees whose collective and peaceful decision to withhold their labor is protected by the NLRA even if economic injury results.”

We need more. When our judges are more familiar with our experiences — whether through advocating for us or through their own similar experiences — that wisdom transforms the justice they dispense.

The right understands very well how past experience informs future performance. Consider that, last month, the law firm Jones Day boasted that it had hired eight clerks from the previous Supreme Court term. Every one of them had clerked for one of the conservative justices — three for Barrett, two for Alito, one for Thomas, one for Kavanaugh and one for Gorsuch. And Jones Day has a strong reputation for union busting. Those associates are the right’s future judicial nominees.

Our future is standing right in front of us. Nicole Berner should be swiftly confirmed — and many more like her in the year ahead.

Rakim Brooks is a public interest appellate lawyer and the president of Alliance for Justice. As a contributor to Democracy Docket, Brooks writes about issues relating to our state and federal courts as well as reforms to our judicial systems.