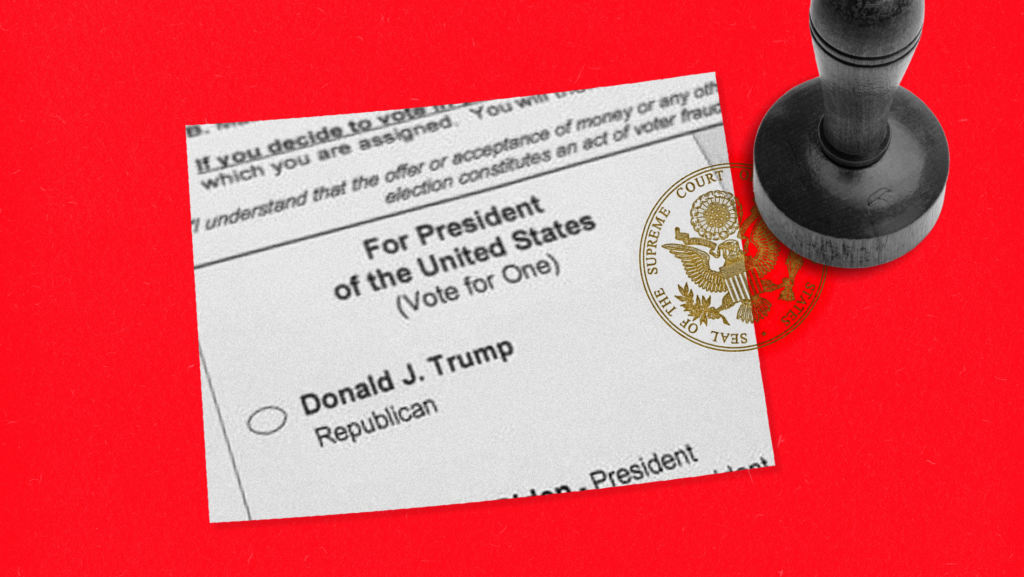

In 9-0 Ruling, Supreme Court Justices Bend Toward Trump

Donald Trump will be on the ballot this November. In a 9-0 decision issued yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Colorado Supreme Court ruling barring him from the ballot under the insurrection clause of the U.S Constitution. While the decision was not a surprise based on the February oral argument, it is still a blow to democracy, the U.S. Constitution and the rule of law. It also reveals some important rifts within the Court.

While the outcome of this case was not in doubt, two questions lingered in the month since oral argument: When would the Court rule and how broad would be its reasoning? We now know the answer to both.

Over the weekend, the Supreme Court posted an updated calendar on its website indicating that an opinion would be handed down on Monday. Clearly one factor in this timing is that the Colorado primary election is today. Another might be the Court’s desire to get some of the big Trump cases off its docket as others come onto it.

Either way, yesterday’s decision told us something about the Court’s ability to decide cases quickly when it wants to. It took the Court only 25 days from the date of oral argument to issue its decision. If the Court applies the same internal schedule, we will have a ruling in the upcoming immunity case by May 17 after it holds oral argument during the week of April 22. This is critical because a mid-May decision would certainly leave enough time for a criminal trial in Washington D.C. to take place before the November 2024 election.

As for the reasoning, I continue to think this was an easy case. Now, I believe it is an easy case the Court got wrong for some good, and some not so good, reasons.

All nine justices essentially agreed that it makes no sense to allow a “patchwork” of state laws and rulings to remove federal officials from the ballot. While they dress up their concern in lofty language, the justices are basically making an argument about practicality.

The Supreme Court docket is long, but for now, at least, it bent toward Trump.

For example, in explaining why states don’t have the power to disqualify under the typically expansive Elections Clause — which allows states to set the time, place and manner of elections — the Court posits that “there is little reason to think that these Clauses implicitly authorize the States to enforce Section 3 against federal officeholders and candidates.”

But of course, there is a reason. At the time the 14th Amendment was enacted, states were charged with administering elections and, indeed, federal elections were more closely tied to their states than even today. Senators were selected by state legislatures and presidential elections were far more focused on the concerns of individual states than national political parties.

In my view, Justice Amy Coney Barrett revealed the Court’s actual motives in her separate concurrence:

In my judgment, this is not the time to amplify disagreement with stridency. The Court has settled a politically charged issue in the volatile season of a Presidential election. Particularly in this circumstance, writings on the Court should turn the national temperature down, not up.

Put simply, the Court allowed Trump to stay on the ballot in order to avoid an outcome that would raise the “national temperature.” My objection is that Judges should not bend to the will of an insurrectionist simply to placate his supporters.

Less obvious in the 13-page unsigned opinion is an important disagreement between the most conservative justices and the three liberals. In somewhat elliptical prose, the conservative majority seemed to slam the door shut on any enforcement of the disqualification provision by federal courts or by Congress other than through specific legislation pursuant to its power under Section 5 of the 14th Amendment.

In practice, this means that federal courts cannot apply disqualification to those convicted of insurrection; nor can Congress do so as part of its certification of election results or in seating members of Congress. As the liberal justices point out, this portion of the opinion was wholly unnecessary to the question at hand. A cynic might say that was intentional.

The silver lining in the Court’s decision is its narrowness. The Court avoided several paths that would have had serious consequences for other, unrelated cases. For example, the Court did not use this case as a vehicle to otherwise limit the 14th Amendment. Nor did it accept the invitation by some to reinvigorate the discredited independent state legislature theory that it rejected last June.

Most importantly, the Court did not absolve Trump of insurrection.

With this case resolved, we now focus our attention on the two other cases before the nation’s highest court. The first, which does not involve Trump directly, is a case by a Jan. 6 defendant challenging the scope of the insurrection statute. That case was argued in January and could impact the legal contours of Trump’s own election interference criminal case in Washington, D.C.

The second is, of course, the immunity case the Court agreed to hear, which is already scheduled for oral argument in late April. If nothing else, the case decided this week demonstrates how fast the Court can decide what it believes are easy legal questions.

Yesterday’s decision may be the first step in resolving the big Trump cases, but it won’t be the last. The Supreme Court docket is long, but for now, at least, it bent toward Trump.