A Strong Democracy Requires True Representation

In the preview for the forthcoming biopic about Shirley Chisholm’s trailblazing 1972 presidential run, an audience member interrupts Chisolm’s address by calling out cynically, “You sound just like every other politician.” Chisolm shoots back: “Do I look like every other politician?”

Implicit in Chisholm’s response is a concept this country is only beginning to understand: representation matters.

As Chisolm’s sharp retort illustrates, change often comes from those who bring descriptive, but, most importantly, substantive representation to the proverbial seat at the table. And while it matters in all contexts, there is perhaps no area more important for representation than voting rights and access to political representation, specifically.

Nearly 60 years after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) and other seminal civil rights laws, communities most impacted by violations of the VRA are often, by virtue of those very violations, not part of the processes that determine their political power. Instead, the same people who have shaped American institutions from positions of power and authority throughout our history wield their power to entrench it for their own benefit.

As a Black woman who has spent most of my decadeslong career as a voting rights lawyer, I have also observed a palpable lack of diversity when sitting on panels, arguing in federal and state courts, teaching in classrooms and collaborating with other organizations on matters of election law and voting rights. I also know Black people continue to be underrepresented in law school admissions — particularly the descendants of enslaved people whose history undergirded civil rights laws like the VRA, as laid bare in a groundbreaking 2022 study.

Black people’s fate and futures are largely being decided by those who lack the expertise and lived experience of anti-Black racism. It is essential for Black people to be centered not merely as the subjects of the law, but also as the agents of change. As the saying goes, “the people closest to the problem are closest to the solution.”

This is not a call to exclude needed allies in our shared commitment to advance racial justice. It is a challenge to bring that commitment to the decision-making processes that must include those most impacted by our laws. It is out of recognition that defending and advancing the rights of Black Americans has shown to have had derivative advancements for all people.

I say this as we confront a moment of real peril for our multiracial and multiethnic democracy, one whose outcome is by no means predetermined. The current political climate is an existential threat to people of all races, ethnicities, genders, sexual orientations or gender identities. The attempted erasure of Black people from our history books, the suppression of our votes at the ballot box, the inability to have full control and agency of our own bodies are only a few of the consequential issues at stake in the 2024 election. And they are a gateway to broader incursions on the rights and freedoms of all Americans.

Those representing the most marginalized voters have an obligation to ensure that they are not only the beneficiaries of their battles, but that they have a seat at the head of the table.

The courts that are rolling back our rights understand the power of the VRA to shape representation based on nearly six decades demonstrating that statute’s effectiveness. In a radical, unprecedented ruling issued late last year, a panel of three judges in the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a lower court’s decision that Arkansas voters — either as individuals or organizations representing them — may not sue to protect their voting rights under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

According to the ruling, only the U.S. Department of Justice, which brings only 10% of voting rights cases, is able to bring litigation to protect the rights of voters. Shockingly, the full 8th Circuit refused to review the panel’s ruling, which prohibits private enforcement of the VRA in the seven states covered by the Circuit: Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota.

The ability of Black people to prosecute violations against them is at significant risk with actions, like the 8th Circuit’s decision, which suppress rather than expand opportunities for those harmed by racial discrimination to seek redress. Given the impact of Black voters on the outcome of elections, this circumscription on enforcement of the right to vote compromises our democracy.

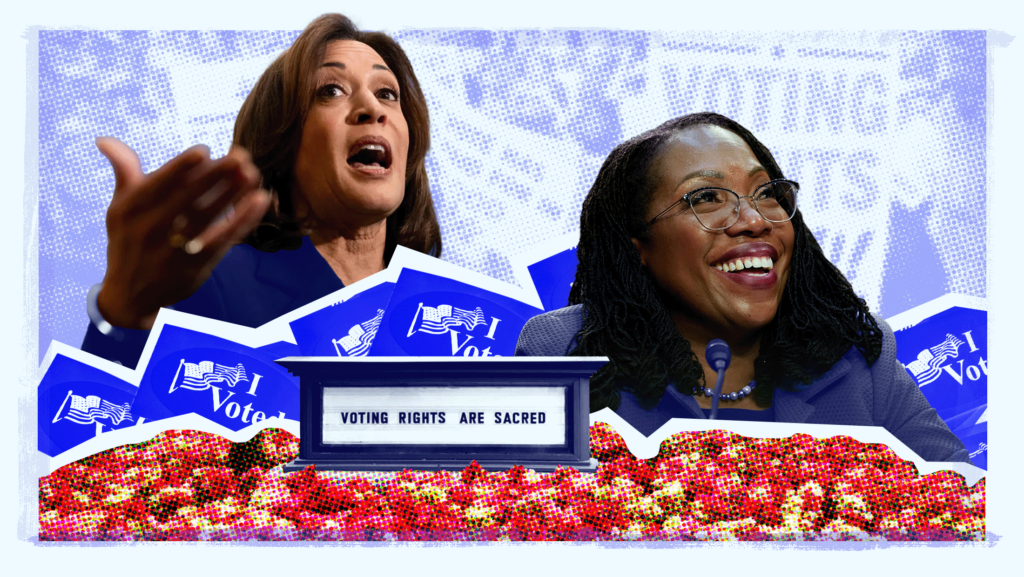

For example, in the 2020 presidential election, 93% of Black female voters cast their ballots for then-candidate Joe Biden, tilting the election in his favor. But the consequences of their votes are much more far-reaching: They helped lead to the confirmation of the nation’s first Black female justice on our highest court and the election of the first Black, the first Asian American and the first female vice president.

Their representation in the electorate was material to the policy consequences of various administrations on issues of importance to our communities. It is, therefore, critical that Black Americans — and all Americans — are able to exercise the most sacred right of citizenship by voting for who will represent them when decisions are made about their futures and daily lives.

The pressing issue of representation, among others, led LDF to launch its Equal Protection Initiative (EPI), in response to the onslaught of attacks by conservative extremists against efforts to increase racial diversity, equity, and inclusion. In the few months of its existence, EPI has issued guidance to colleges and universities, as well as private employers and funders, about the continuing moral and legal responsibility to ensure that opportunities are equal to all.

Racial diversity is not only essential to create the most dynamic learning environment or the most successful economy, but also it is crucial for the integrity and survival of our multiracial democracy. Representation matters, not for the purpose of using diversity to improve outcomes and redress past and present discrimination, but for diverse representation in our colleges and universities, board rooms and halls of government, which helps to equalize opportunities that have been denied to Black people and other marginalized communities for too long.

The same holds true for the representation of women in politics. The laudable work of women’s civic organizations like the Higher Heights Leadership Fund have led to a marked increase in the number of women who run for office. These and like organizations are investing in a long-term strategy to expand and support leadership pipelines for Black women at all levels and strengthen their civic participation throughout the year, beyond just Election Day.

History will judge what we do today to shape tomorrow. The people who represent us impact our success personally and as a community in myriad ways. And those representing the most marginalized voters have an obligation to ensure that they are not only the beneficiaries of their battles, but that they have a seat at the head of the table.

Janai Nelson is the president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.