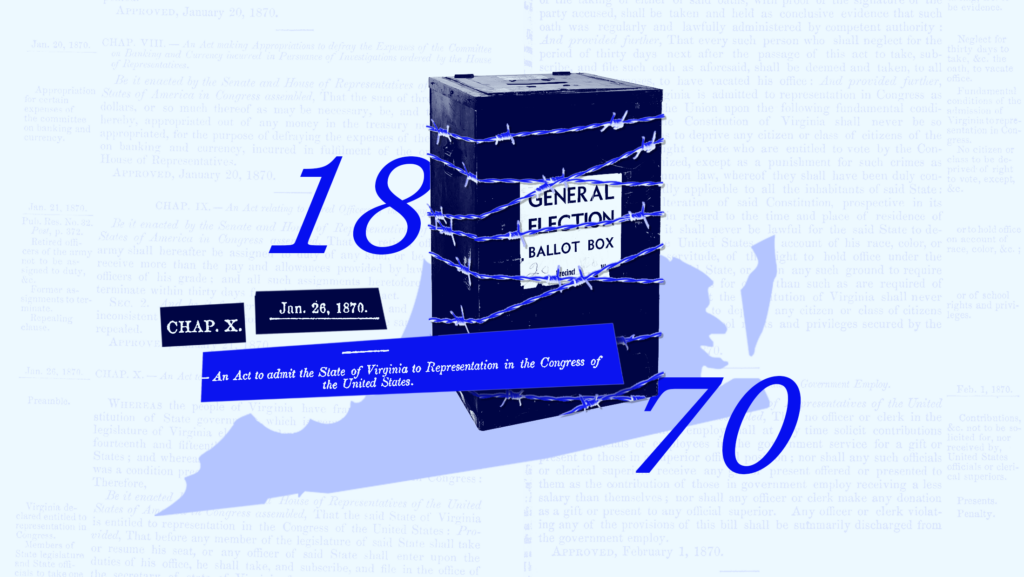

Virginia’s Felony Disenfranchisement Provision Faces a New Legal Challenge Under This 150-Year-Old Law

Over 150 years ago, in the midst of the Reconstruction era, Congress enacted the Virginia Readmission Act, a federal statute that enabled the Commonwealth of Virginia to gain federal representation in Congress following the Civil War.

As a former Confederate state, Virginia’s entitlement to congressional representation was contingent on its ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution — which guaranteed citizenship, equal protection, due process and voting rights to formerly enslaved Black citizens — as well as its enactment of a state constitution that guaranteed universal male suffrage. In addition to these prerequisites for readmission, the Act imposed express prohibitions on the commonwealth’s ability to disenfranchise its citizens going forward, except in a limited set of circumstances.

Despite this federal mandate, the Virginia Constitution, as it stands today, contains one of the strictest felony disenfranchisement provisions in the country, and accordingly, maintains one of the highest rates of felony disenfranchisement in the United States.

At the end of June, voting rights groups resurrected the 150-year-old Virginia Readmission Act as the basis for a novel legal challenge to the commonwealth’s lifetime ban on voting for individuals with any felony conviction. By arguing that the Virginia Constitution’s felony disenfranchisement provision violates a Reconstruction-era law, the new lawsuit demonstrates the ingenuity of leveraging a seemingly antiquated statute to attain justice in contemporary times.

The new lawsuit relies on the text of the 1870 Virginia Readmission Act, which states that Virginians can only be disenfranchised for a narrow set of crimes.

Under the 1870 Virginia Readmission Act, which remains in effect today, the commonwealth is required to adhere to certain ongoing conditions in order to maintain its representation in Congress. One such condition stipulates that the Virginia Constitution should “never be amended or changed as to deprive any citizen or class of citizens of the right to vote…except as a punishment” for an exhaustive list of crimes that were considered “felonies at common law” in 1870. Common law is a body of law derived from England upon which the United States’ then-nascent 19th century legal system was based.

King v. Youngkin, the federal lawsuit filed in June that challenges Virginia’s felony disenfranchisement provision, specifically focuses on this aspect of Virginia’s Readmission Act. The case was brought on behalf of Bridging The Gap In Virginia — a nonprofit organization that focuses on empowering formerly incarcerated individuals and re-integrating them into society — along with three Virginia residents who are disenfranchised due to former felony convictions.

According to the lawsuit, the Virginia Readmission Act only permits Virginia to deny voting rights to those who were convicted of crimes that were considered “common law” felonies in 1870. These crimes include murder, manslaughter, arson, burglary, robbery, rape, sodomy, mayhem and larceny.

Relying on the text of the 1870 statute, the plaintiffs contend that “the Virginia Readmission Act explicitly prohibits the Commonwealth of Virginia from adopting constitutional provisions that disenfranchise citizens other than those convicted of crimes that were felonies at common law in 1870.” The lawsuit posits that as a result of Virginia’s far-reaching felony disenfranchisement provision, “an estimated 312,540 Virginians are disenfranchised, rendering Virginia the state with the fifth highest number of citizens disenfranchised for felony convictions, and the sixth highest rate of disenfranchisement.”

Richard Walker, the founder and CEO of Bridging The Gap In Virginia, who is himself a formerly incarcerated Virginia resident, explained the significance of the case to Democracy Docket: “Virginia has been violating [federal] law for over 150 years, stripping people, particularly Black people, of their voting rights…It’s high time that Virginia started following the law…that is the main impetus of the lawsuit.”

Walker has helped restore voting rights to over 10,000 formerly incarcerated individuals since being released from prison in 2005. He elaborated on how the lawsuit relates to his organization’s core mission of helping formerly incarcerated individuals re-enter mainstream society. “I’ve devoted much of my time since coming out of prison to helping other folks re-enter back into society…I know firsthand that having the right to vote is of critical importance to making people feel they have a voice…[Virginia’s felony disenfranchisement provision] amounts to a lifetime of sentencing…when you come out of prison and still face barriers because of the [state constitution], it is just not fair.”

According to the lawsuit, the Virginia Constitution’s felony disenfranchisement provision clearly violates the Virginia Readmission Act.

Although the Virginia Readmission Act specifically bars the commonwealth from disenfranchising its citizens for crimes that were not classified as felonies during 1870, Virginia’s Jim Crow-era Legislature flouted this rule by amending subsequent iterations of its state constitution to broaden the scope of disenfranchising crimes. Today, the Virginia Constitution retains a 1902 provision that automatically disenfranchises individuals who are convicted of “any felony, regardless of whether the crime was a felony at common law in 1870.” Steeped in white supremacy, the 1902 provision was enacted with the “express goal of suppressing the voting rights of Black citizens,” the lawsuit states.

In turn, the new lawsuit alleges that the Virginia Constitution directly contravenes the Virginia Readmission Act, since it disenfranchises citizens for a much more expansive set of crimes than those that were considered felonies in 1870. Ultimately, the plaintiffs ask a federal court to declare the Virginia Constitution’s felony disenfranchisement provision in violation of the Virginia Readmission Act and to block its enforcement.

The commonwealth’s stringent felony disenfranchisement provision disproportionately harms Black Virginians.

The lawsuit, in addition to asserting that the Virginia Constitution violates the 1870 law, underscores how Virginia’s Black citizens are disparately harmed by the commonwealth’s lifetime ban on voting for those with any felony conviction. “Although Black Virginians comprise less than 20% of Virginia’s voting age population, they account for nearly half of all Virginians disenfranchised due to a felony conviction. Felony disenfranchisement among Black voting-age Virginians is nearly two-and-a-half times as high as the rest of Virginia’s voting-age population,” the lawsuit notes.

In addition to the staggering rate of felony disenfranchisement among the commonwealth’s Black citizens, the lawsuit highlights how relative to the United States’ population at large, Black Virginians fare a lot worse: “The rate of felony disenfranchisement among Black voting-age Virginians [12.6%] is more than twice as high as the rate of felony disenfranchisement among the entire United States Black voting-age population [5.28%].”

The case also points to the fact that the Virginia Constitution’s wholesale disenfranchisement of individuals convicted of “any felony” — as opposed to the narrow list of 1870 “common law” felonies — has especially pernicious effects on Black citizens. Over the past century, Virginia has veritably expanded the scope of crimes that it classifies as felonies, many of which did not even exist at the time of the 1870 Virginia Readmission Act.

“Among the numerous crimes currently defined as ‘felonies’ by Virginia that were not felonies at common law in 1870 are controlled substance offenses,” the lawsuit states, adding that “[i]n 2020, 72% of all drug-related arrests in Virginia were of Black citizens.” Indeed, two of the lawsuits’ individual plaintiffs, Tati King and Toni Johnson, are both disenfranchised due to former drug-related offenses despite having been released from incarceration.

In March 2023, “the dire impact of Virginia’s sweeping disenfranchisement provision” was compounded by Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s termination of automatic rights restoration.

Although Virginia’s constitution disenfranchises people for life after a felony conviction, the commonwealth’s previous three governors streamlined voting rights restoration. In 2013, Gov. Robert McDonnell (R) automatically restored rights to people convicted of nonviolent felonies after the completion of their entire sentence. Democratic Govs. Terry McAuliffe and Ralph Northam built upon that policy: In 2016, McAuliffe expanded rights restoration to all individuals after the completion of their sentences and in 2021, Northam moved forward the restoration timeline from after the completion of a sentence, which includes probation and parole, to after release from incarceration. Over 300,000 individuals regained voting rights during this period.

However, back in March — in a notable departure from his predecessors — Gov. Glenn Youngkin (R) terminated the commonwealth’s previously automatic rights restoration scheme and replaced it with a policy that only allows for rights restoration on a case-by-case basis at the governor’s discretion. Consequently, Virginia is now the only state in the country that permanently disenfranchises individuals with former felony convictions, unless they receive individual approval to be re-enfranchised by the governor. In response to this rollback, pro-voting litigants filed a separate federal lawsuit challenging Virginia’s newly restrictive voting rights restoration process for violating the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

According to Walker, whose voting rights were restored under McDonnell’s administration in 2012, Youngkin is not merely undoing the progress made by his predecessors. “It’s beyond undoing, it is sabotaging…going back to Jim Crow. We thought we had an open door for change, but now Youngkin has just completely shut that door.”

Nevertheless, Walker remains hopeful that the new legal challenges against Youngkin will prevail: “We are hoping and believing…that these lawsuits will be able to correct the wrongs that have been going on for over 150 years. It’s time for [Youngkin] to wake up and realize we’re not going to allow him to just come in here and dictate things to us that…take us backwards and not forwards.”

In light of Youngkin’s hampered rights restoration process, the legal challenge to Virginia’s felony disenfranchisement provision comes at a critical time.

As other states, including Minnesota and New Mexico, are implementing progressive measures to restore voting rights to thousands of individuals with former felony convictions, Virginia is reverting back to an early 1900s-era policy that was enacted with the explicit intent to disenfranchise Black citizens.

Earlier this week, the Virginia NAACP held a press conference urging the Youngkin administration to adopt its proposed platform that establishes non-arbitrary and publicly available criteria for rights restoration. By maintaining one of the strictest felony disenfranchisement schemes in the country, while simultaneously foreclosing opportunities for rights restoration, “Gov. Youngkin has taken us back to 1902,” stated Ryan Snow, counsel for the Lawyer’s Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

Bridging The Gap In Virginia’s new legal challenge to the commonwealth’s sweeping felony disenfranchisement provision presents a crucial opportunity for a federal court to weigh in on a unique set of arguments brought under a 150-year-old Reconstruction-era statute. Even more importantly, this case offers the court a chance to redress past wrongs and potentially re-enfranchise tens of thousands of Virginians.