Black Voters Fight To Be Seen in Three Lawsuits That Could Impact State Judicial Selection

UPDATE: On July 25, 2023, a federal judge dismissed the Arkansas lawsuit challenging the methods used to elect Arkansas Supreme Court justices and appellate court judges.

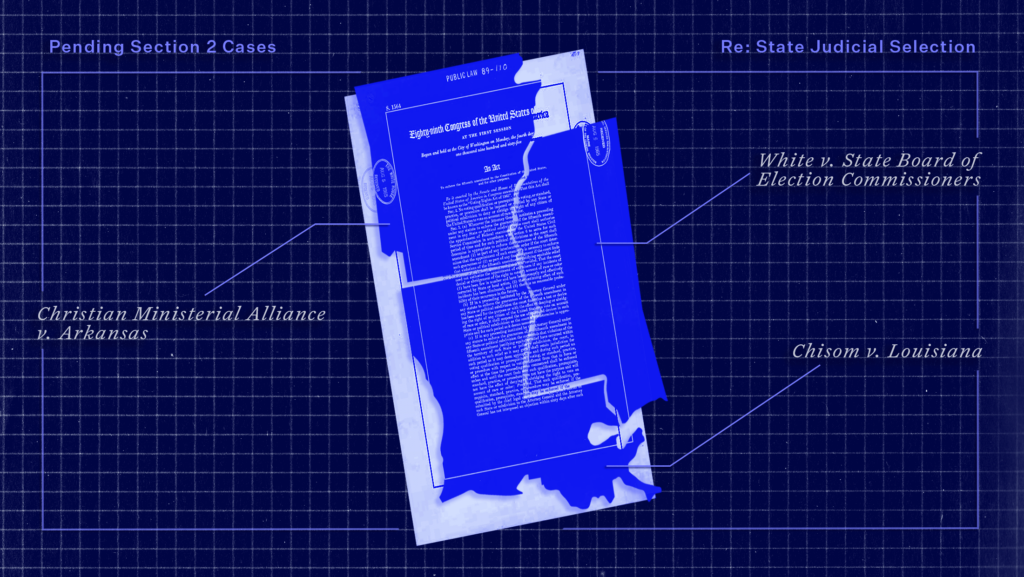

On June 8, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Allen v. Milligan, which upheld Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). In light of this decision, over 30 ongoing lawsuits with pending Section 2 claims will proceed in due course. There are three particular cases with Section 2 claims that focus on the way people can elect their judicial representatives in Louisiana, Arkansas and Mississippi.

Only 24 states elect justices to their respective state Supreme Courts. Of those 24, eight hold partisan elections, Louisiana included, while the majority of states with supreme court elections, including Arkansas and Mississippi, hold nonpartisan elections. However, as was this case this past spring in Wisconsin, even the nonpartisan elections have become contentious with judicial candidates signaling their stances on issues ahead of Election Day.

As state legislatures grow more extreme in their efforts to flip the democratic process on its head and remove the power of their constituents, state Supreme Courts are critical in holding lawmakers accountable.

These three state Supreme Court cases will proceed following the Allen decision that challenge the methods in which judges are elected to the state supreme courts and could have consequential outcomes for state judicial selection.

Chisom v. Louisiana

Filed: Sept. 19, 1986

Background: In 1986, Black voters filed a lawsuit in federal court against the state of Louisiana alleging that the method used to elect the seven justices of the Louisiana Supreme Court violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). The district court sided with the state and ruled that the election system did not violate the VRA. The Black voters appealed, and the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals also sided with the state, holding that the Section 2 of the VRA did not apply to judicial elections.

Eventually, the case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 1991 that state judicial elections are, in fact, protected under Section 2. After the Court sent the case back down to the 5th Circuit, the parties entered into a consent decree (an agreement) to ensure that Louisiana’s state Supreme Court elections did not violate Section 2 and created a temporary eighth seat, known as the Chisom seat. In 1997, the Chisom seat was dissolved after legislation created a majority-minority Supreme Court district in Orleans Parish, but the consent decree still remained in effect.

Status: In 2012, the case reopened over chief justice disagreements. The most senior justice, Justice Bernette Johnson, first held the Chisom seat as the court’s second Black justice prior to being elected to the Orleans Parish district. Johnson’s colleagues did not want her time in the Chisom seat to count toward her tenure, so she asked the federal district court to enforce the consent decree. The district court granted Johnson’s request to enforce the consent decree and she served as chief justice until her retirement in 2020.

In 2021, the state moved to dissolve the 1992 consent decree. In May 2022, the district court declined to grant this request after finding that the consent decree was still necessary “to ensure compliance with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.” The state appealed this decision to the 5th Circuit where litigation is ongoing.

Importance: The Chisom case — particularly its reopening — highlights the need to keep tools that protect minorities, like the consent decree, in place and how voters are still fighting to have their voices heard 40 years later.

Critically, this consent decree led to Louisiana electing its first Black Supreme Court justice, Revius Ortique Jr., in 1992. But this case extends beyond Louisiana as it is the reason why judicial elections are covered under Section 2, thus paving the way for future challenges of state Supreme Court districts under Section 2.

This consent decree has been working, but there’s a risk that without it, we will return to the landscape that we had in the late 1980s and 1990s where it was an all white judiciary and that’s unacceptable…In short, have circumstances materially changed…since the consent decree went into effect? The sad reality is, the answer is no, because the situation on the ground is largely the same for Black Louisianians.

Christian Ministerial Alliance v. Arkansas

Filed: June 10, 2019 | Dismissed: July 25, 2023

Background: In 2019, the Christian Ministerial Alliance, Arkansas Community Institute and Black voters filed a lawsuit against the state of Arkansas, Gov. Asa Hutchinson (R), Secretary of State John Thurston (R), Attorney General Leslie Rutledge (R), the Arkansas Board of Apportionment and the Arkansas Board of Election Commissioners. The plaintiffs argue that the at-large districts used to elect state Supreme Court justices and the combined single-member and multi-member districts used to elect judges to the Arkansas Court of Appeals violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) by diluting the voting strength of Black voters in Arkansas. The plaintiffs request the adoption of new election methods.

Status: In February 2021, the court dismissed the claims against the state of Arkansas, the Board of Election Commissioners and the Board of Apportionment, holding that the claims against these entities are barred by sovereign immunity — a legal doctrine that largely bars government officials from being sued. The plaintiffs’ claims against the remaining defendants — the governor, the secretary of state and the attorney general — moved forward to trial, which was held on April 25, 2022. We are waiting on a decision from a federal district court.

Importance: This case is critical in the fight to ensure that Black Arkansans have their voices heard and have the opportunity to be represented by their preferred candidate in their state Supreme Court. Although 15% of the population is Black, as the complaint states, no Black candidate has ever won a statewide race, despite Black Arkansans voting as a bloc and being geographically compact, in part due to racially polarized voting.

Arkansas’ Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals render consequential decisions that deeply and directly affect the lives of all Arkansans, including Black voters whose power to elect judges on these courts is stifled by the courts’ current electoral structures.

White v. State Board of Election Commissioners (Mississippi)

Filed: April 25, 2022

Background: In 2022, Black Mississippians filed a lawsuit against the State Board of Election Commissioners, Gov. Tate Reeves (R), Attorney General Lynn Fitch (R) and Secretary of State Michael Watson (R) challenging the districts used for electing justices to the Mississippi Supreme Court. The plaintiffs allege that the system used for electing justices to Mississippi’s nine-member state Supreme Court dilutes the voting strength of Black Mississippians in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA).

“Mississippi’s population is almost 40 percent Black — a greater proportion than any other State in the nation. Yet in the 100 years that Mississippi has elected its Supreme Court by popular vote, there have been a total of only four Black justices ever to sit on that body,” the complaint notes. According to the complaint, since 1987, Mississippi has utilized the same three at-large districts — which “were drawn by the Legislature over the objections of Black lawmakers” — to elect its nine state Supreme Court justices.

Status: Litigation is ongoing and a trial is scheduled for May 13, 2024.

Importance: This case is critical in the fight against racial vote dilution in Mississippi, which prevents Black voters from being able to elect their candidate of choice. As the complaint states, “Voting is heavily polarized on the basis of race across Mississippi—indeed, no Black candidate has won statewide office in Mississippi in the 140 years since Reconstruction.” This lawsuit provides an avenue to remedying that injustice.

Black voting strength is diluted—submerged across white-majority districts—and Black voters are denied an equal opportunity to elect candidates of choice to the Mississippi Supreme Court, in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

There are a number of reasons to pay attention to these three cases and what is happening in state Supreme Courts across the country.

First, experts argue that the decision in Moore v. Harper increases the stakes of state Supreme Court races. As a consequence of the decision, we can expect Democrats and Republicans alike to pay more attention to the election of values-aligned judges, meaning it is likely we will see more expensive judicial races like the one in Wisconsin this past April.

The role of state Supreme Courts was also reaffirmed in Moore when the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the independent state legislature theory and maintained that state Supreme Courts could intervene when necessary.

As state legislatures grow increasingly extreme and polarized in their policies with opportunities for accountability removed via gerrymanders, a state Supreme Court is one of the only ways to pursue justice when legislators abuse that power. State legislatures are already working to remove remaining entry points for citizens, like ballot measures, so state Supreme Courts play an integral role in ensuring that democracy is maintained at the local level.

Finally, and most simply, these cases are striving to meet the long-unfulfilled democratic ideals of the United States. Every voter — no matter their skin color, zip code or party affiliation — is deserving of the opportunity to fairly elect the candidate of their choice.

As the plaintiffs in Mississippi assert, all voters should be “afforded the opportunity to participate in politics with equal dignity and equal opportunity to elect representatives of their choice.”