How SCOTUS Might Determine the Future of the Voting Rights Act

In October 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in Merrill v. Milligan, a case that will determine the future of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). The case centers on whether Alabama violated Section 2 of the VRA when it enacted a congressional map that created one rather than two majority-Black districts.

Section 2 prohibits any voting law or redistricting map that results in a “denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” In November 2021, pro-voting groups sued the state of Alabama under Section 2 after the Legislature redrew political districts with 2020 census data. In January 2022, a federal three-judge panel determined that Alabama’s congressional map likely violated Section 2 of the VRA, but the Supreme Court paused the panel’s order. At that time, Chief Justice John Roberts dissented alongside the liberals: “[I]n my view, the District Court properly applied existing law in an extensive opinion with no apparent errors for our correction.”

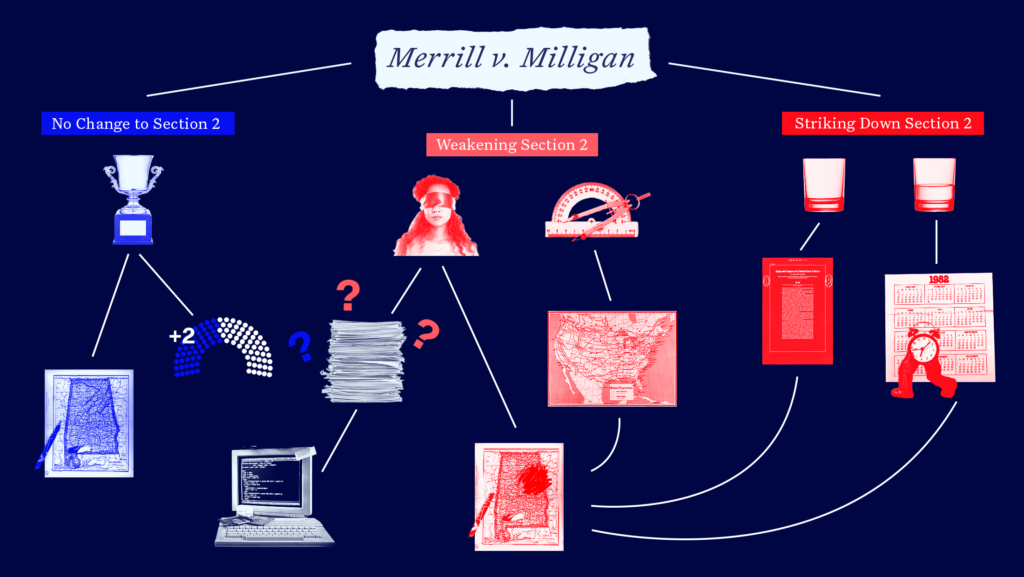

The fact that the Supreme Court decided to hear this lawsuit, which Justice Elena Kagan called an “easy case” during oral argument, suggests that the justices want to review the jurisprudence around Section 2. If the Court rules in favor of the pro-voting groups who brought the initial lawsuit and affirms the three-judge panel’s prior decision, it would be the best case scenario: maintaining the current use of Section 2 and increasing representation for Black voters in Alabama and other districts across the country.

While we don’t know how the nine justices will ultimately rule, there are a number of ways the Court could severely undermine the landmark voting rights protection. Below we outline a few of those potential outcomes.

The Supreme Court could radically upend Section 2 of the VRA.

If the Court sides with Alabama and reverses the lower panel’s decision, it could take direct aim at the most litigated portion of the VRA.

A decision ruling that Section 2 of the VRA is unconstitutional.

The Court could rule that Section 2 of the VRA is unconstitutional by requiring an impermissible use of race in violation of the 14th Amendment. This would have widespread implications for both redistricting and voting law cases. It would also be counter to the long-standing history and 58-year legacy of the VRA, though the Court could assert that it has always assumed, without deciding, the constitutionality of Section 2. (In contrast, it has explicitly endorsed the constitutionality of Section 5 before gutting it in 2013.) During oral argument, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson rejected the idea that Section 2 is unconstitutional because it references race: “When I read Section 2, I don’t see that Congress is requiring race neutrality…It seems as though Congress is authorizing the consideration of race.” Jackson also utilized the conservative’s favorite tool, originalism, to argue that the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments were enacted purposely with race in mind.

A decision ruling that the 1982 amendments to Section 2 are unconstitutional.

In City of Mobile v. Bolden (1980), the Supreme Court held that Section 2 does not afford any additional protections beyond the 15th Amendment, which ensures that the right to vote is not denied on “account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” In response to this ruling, Congress amended the VRA just two years later to make its protections more robust, adding that it is unlawful for the “results” of a voting process to abridge the right to vote. These 1982 amendments, known as the results or effects test, created the possibility to challenge laws that had a discriminatory impact, even without proving a discriminatory intent.

Forty years later, the Supreme Court could rule in Merrill that the 1982 amendments results test are unconstitutional because they go beyond the scope of the 15th Amendment. If SCOTUS reverts us to the pre-1982 version of the VRA, voting protections would be severely weakened: In general, lawmakers don’t go on the record announcing their racist intentions so almost all cases prevail on the results test.

Short of declaring the law unconstitutional, there are numerous ways the Court could severely undermine the efficacy of Section 2.

A decision ruling narrowly that the proposed second majority-Black district in Alabama is not “compact,” “reasonably configured” or fails to fulfill other criteria.

At the argument in October, Justice Brett Kavanaugh seemed fixated on the concept of compactness and other elements of how a district is configured. Law professor Rick Pildes asserted that an opinion focused on the factual issues of “whether a proposed VRA district is reasonably configured” would likely be “the narrowest grounds” on which the Court might overturn the lower court decision. But, the effects could still be devastating, providing a roadmap for states to challenge and overturn VRA-protected districts.

A decision focusing on computer simulations to weaken the Gingles test.

For decades, courts have relied on a test established in the 1986 case Thornburg v. Gingles to determine whether a map dilutes the votes of a racial minority. In a similar vein to overturning the 1982 amendments, the Court could weaken this method of determining discriminatory results. The Gingles test contains three factors that must be met to prove racial vote dilution: (1) The minority group in question must be “sufficiently large and geographically compact” to constitute a political district; (2) the minority group must be “politically cohesive,” meaning the group generally votes for similar candidates and (3) the majority group must also be “politically cohesive” by voting to defeat the preferred candidates of the minority group.

The Supreme Court might weaken the first prong of this test by pointing to testimony that emerged during a hearing prior to the lower court’s decision in January 2022. According to the state of Alabama, the testimony from one expert witness demonstrated that without considering race, none of the two million computer simulated maps that she generated in her research created a second majority-Black district. This evidence was not raised for the Section 2 claims at issue now, but the justices nevertheless latched onto this point in oral argument.

It’s unclear how computer simulations will ultimately play into the Court’s decision, as the justices may be hesitant to incorporate new technology into legal tests. However, a majority of justices could say that Section 2 does not permit the creation of a district that would never have been created by a neutral map drawer — in this case, a computer algorithm. Thus, the Court could require a randomly drawn race-blind plan (instead of a “reasonably configured” plan) to satisfy the first Gingles factor. Since the first Gingles factor is expressly not race blind, such a ruling would mean that Alabama could not draw a second majority-Black district and numerous other redistricting cases would be implicated. This outcome would likely spur more litigation and pull the use of computer algorithms into more cases.

Voters will suffer if the Supreme Court overturns the lower court’s decision.

There’s no good way for the Court to overturn the lower court’s decision: It will either undermine Section 2 of the VRA in an explicit and clear way or it will do so in a more nebulous but no less devastating manner.

If the Court overturns the lower court’s decision, Black voters in Alabama will suffer the real-life and decades-long consequences of inadequate representation. Then, the state most immediately implicated by a decision is Louisiana, where a parallel case challenging the state’s congressional map for diluting the voting strength of Black Louisanians in violation of Section 2 remains open. Just like in the Alabama case, a federal court blocked the Louisiana map for likely violating the VRA, but the Supreme Court reinstated the map and paused the case pending a decision in Merrill.

Meanwhile, there are 21 other Section 2 redistricting cases, largely challenging maps drawn by Southern states, awaiting decisions. The trajectory of these cases will be determined by the Court’s decision about Alabama’s congressional map. We can expect a consequential ruling in late spring or early summer 2023, likely right before the Supreme Court recesses for the summer.