How One Local Republican Is Trying To Invalidate Washington State’s Voting Rights Act

On May 9, 2022, voting rights advocates rejoiced after Latino voters reached a historic settlement agreement with Franklin County, Washington that would pave the way for long overdue Latino representation in the county’s local government. Under the agreement, the county’s Latino population — which accounts for over 50% of Franklin County’s total population — would be able to elect a candidate of their choice to the three-member Franklin County Commission for the first time in over two decades beginning in the 2024 election cycle. As Franklin County’s primary governing body, the Franklin County Commission sets the county’s budget and oversees programs and services pertaining to public health, environmental protection, housing, public services and more.

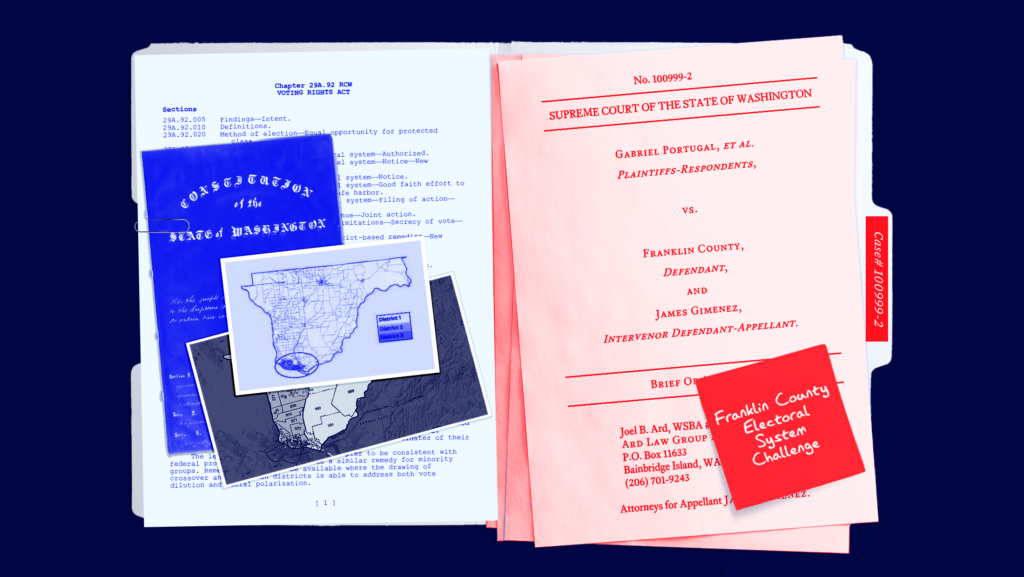

Importantly, this successful settlement arose from the second-ever lawsuit, Portugal v. Franklin County, brought under the Washington Voting Rights Act (WVRA). Enacted in 2018, the WVRA is state law modeled after certain aspects of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965, that was established to ensure “minority groups have an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice or influence the outcome of an election.” The first lawsuit brought under the WVRA in Yakima County, Washington culminated in a successful settlement in 2021 that similarly benefited Latino voters. Just last month, the Washington Legislature enacted an amended version of the WVRA that provides even more robust protections to the state’s electorate.

On Thursday, May 11, 2023 — nearly one year after the Franklin County settlement in Portugal v. Franklin County — the Washington Supreme Court will hear a direct constitutional challenge to the WVRA stemming from the very same lawsuit. Curiously, neither of the original parties to the lawsuit is behind this head-on challenge to the WVRA; rather, it comes from an outside Republican intervenor who became involved in the lawsuit nearly six months after it was filed.

How did a previously resolved case out of Franklin County morph into the vehicle through which a Republican intervenor is attempting to strike down the WVRA in its entirety?

In April 2021, Latino voters in Franklin County filed the second ever lawsuit under the WVRA.

Over two years ago, the League of United Latin American Citizens and three Latino voters filed a complaint challenging Franklin County’s hybrid electoral scheme for allegedly diluting Latino voting power. Under this regime for electing members to the Franklin County Commission, the county utilized an at-large electoral system in general elections whereby commissioners were elected by voters across the entire county. In contrast, the county employed a separate, district-based system in primary elections.

The Latino voters claimed that Franklin County’s district-based election method for primary elections “dilutes the votes of Latino/a voters in Franklin County” since it “break[s] up the cohesive and compact Latino community by splitting voters across three districts” despite the fact that the “Latino community is large enough and sufficiently geographically compact to comprise a majority-minority district.” According to the complaint, Latino voters constitute over 33% of Franklin County’s citizen voting-age population. Concurrently, the plaintiffs contended that the at-large election method that the county used for general elections, “further dilutes Latino voting power, because there is racially polarized voting during county elections which operates to block Latino voters from electing candidates of their choice.”

The lawsuit argued that this bifurcated electoral system, combined with Franklin County’s history of discrimination, rendered the county’s Latino voters unable to elect candidates of their choice in violation of the WVRA. In turn, the plaintiffs asked a state trial court to implement a new electoral system that complies with the WVRA.

Prior to the settlement, a trial court ruled in favor of the Latino voters and against a local GOP official who intervened in the midst of litigation.

On Sept. 13, 2021, a Washington trial court judge granted the Latino plaintiffs’ requested relief and ordered the parties to work cooperatively “to implement a single member district-based voting system for the primary and general elections for Franklin County Commissioner Elections” before the November 2022 elections. However, before the order was implemented, the court voided this ruling at the request of the Franklin County Commission, which argued that its attorneys agreed to the order without the commission’s consent. Consequently, there was no remedy in place for the 2022 elections, but the plaintiffs subsequently filed a renewed request for relief from the court.

Meanwhile in September 2021 — nearly six months after the lawsuit commenced — a Franklin County GOP precinct committee officer, James Gimenez, intervened in the lawsuit and asked the court to declare the WVRA in violation of the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Washington Constitution and the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution. The Latino plaintiffs later claimed that Gimenez “was in cahoots” with Franklin County Commissioner Clint Didier (R), one of the named defendants in the lawsuit. According to the plaintiffs, Didier facilitated Gimenez’s intervention in the lawsuit and “privately worked with Gimenez and his counsel to subvert the settlement.” “Commission Didier not only encouraged, but explicitly directed…Gimenez’s action designed to torpedo the WVRA settlement,” they alleged.

Upon receiving permission from the court to intervene, Gimenez argued that the WVRA “explicitly…makes race the predominant factor” in redistricting wherever it is invoked and that the plaintiffs “lack standing” (meaning capacity to sue) since they are not “members of a protected [minority] class” under the WVRA. The trial court rejected Gimenez’s challenge on Jan. 3, 2022, and held that the WVRA is indeed constitutional under both the federal and state constitutions.

Then, in what was ostensibly the resolution of the lawsuit on May 9, 2022, the trial court entered a settlement agreement to implement single-member districts, including one majority-Latino district, by 2024. In the same order, the court also dismissed the lawsuit, thereby concluding litigation.

“We are truly pleased about the settlement. The Franklin County Commissioners have admitted that they are in violation of the [WVRA]. Now the County’s election system will be changed,” stated Gabriel Portugal, one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit. “Many voters including Latinos in Franklin County now have the right to elect a candidate within their district. This right is an essential part of our democracy. We believe this is a win for everyone in Franklin County,” he continued.

Despite a successful settlement resolving the case, the GOP intervenor is continuing his quest to nullify the WVRA.

In June 2022, the GOP intervenor appealed the trial court’s decision denying his request to strike down the WVRA to the Washington Supreme Court. On appeal, Gimenez asks the Washington Supreme Court to void the May 9, 2022 settlement and declare the WVRA unconstitutional on its face, largely reiterating his arguments that were previously rejected by the trial court.

In addition to re-asserting that the Latino voters behind the lawsuit lack standing, Gimenez once again suggests that the WVRA amounts to a “racial gerrymander” since it “makes race the predominant factor in districting, and grants elections and voting privileges to certain groups over others” in contravention of both the U.S. and Washington Constitutions.

Conversely, Latino voters rebut the GOP intervenor’s arguments and urge the state Supreme Court to uphold the WVRA.

On the other side, the Latino voters ask the Washington Supreme Court to reject Giminez’s allegedly specious claims, arguing that he wholly misinterprets the WVRA and rests his claims on shaky legal ground. The Latino voters, in addition to maintaining that they have standing to sue under the WVRA, argue that the WVRA complies with both the United States and Washington Constitutions.

In refuting Giminez’s contention that the WVRA uses race as a predominant factor in redistricting, the Latino voters assert that the “WVRA does not permit political subdivisions to use race however they may see fit in remedying vote dilution.” Rather, “[w]ith the WVRA, like the [federal Voting Rights Act], race conscious redistricting is permitted in the limited context of remedying past and current [racial] discrimination in voting with[in] the challenged jurisdiction,” they explain in their brief submitted to the Washington Supreme Court.

Accordingly, the Latino voters underscore Franklin County’s history of discrimination towards its Latino residents “in a variety of areas such as education, housing, and employment” that has been further exacerbated by the county’s election system, which prevents Latino voters from electing candidates of their choice.

Finally, the Latino plaintiffs, joined by numerous amici curiae (“friends of the court”), point to a preponderance of legal precedent to support the constitutionality of the WVRA. In California for instance, both a federal and state court upheld the 2002 California Voting Rights Act under both the U.S. and California Constitutions.

“[T]his case could have resonance outside of Washington State,” Ruth Greenwood, the director of Harvard Law School’s Election Law Clinic, told Democracy Docket. Greenwood, who submitted an amicus brief in support of the Latino voters, explained how if the intervenor is unsuccessful before the Washington Supreme Court, he could file a petition in the U.S. Supreme Court asking that it strike down the WVRA for violating the federal constitution. “A finding along those lines could put other [state-level VRAs] in jeopardy,” she added.

As the Washington Supreme Court is poised to rule on the constitutionality of the WVRA, the Washington Legislature recently amended the Act to further enhance its protections.

In April 2023, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee (D) signed House Bill 1048, which will augment and improve the enforcement mechanisms of the WVRA starting on Jan. 1, 2024. The law — which enhances the WVRA’s existing protections — instructs courts to construe all election laws and administrative orders “liberally in favor of [p]rotecting the right to cast an effective ballot” and ensuring that all voters have equal access to the ballot box. In adjusting the remedy process under the WVRA, the amended Act notes that courts “may not give deference to a proposed remedy only because it is proposed by the political subdivision.”

Additionally, H.B. 1048 expands upon who has the right to sue to include indigenous tribes and coalitions of multiple racial or language groups, allows those who successfully challenge an election system under the WVRA to recoup incurred costs, revises certain definitions in the WVRA and more.

H.B. 1048 “makes the Washington Voting Rights Act more accessible and practical for communities to use,” stated Washington State Sen. Sharlett Mena (D), the law’s lead sponsor. “We created the WVRA to ensure that every vote matters” and H.B. 1048 guarantees that “every Washington voter can unlock its promise.”

State-level VRAs serve as a crucial tool in protecting voting rights at the local level.

In addition to Washington, states including California, Oregon, Virginia and New York have also adopted state-level VRAs, while others including Connecticut, Maryland and New Jersey are looking to enact them. As protections for minority communities under the federal VRA have eroded over the past decade, state-level VRAs are becoming increasingly salient in protecting voting rights at the local level. “[State-level VRAs] are one of our best hopes, short of federal legislation, to fight back against the U.S. Supreme Court’s hostility to federal voting rights’ claims,” Greenwood said.

Although a Republican intervenor is attempting to throw out the WVRA via the courts, the Legislature’s recent amendments to the Act suggest that it is largely popular and here to stay. While it is up to the Washington Supreme Court to decide the fate of the WRVA at tomorrow’s oral argument, lawmakers and advocates alike are hopeful that this pro-voting law will remain on the books.

According to Greenwood, tomorrow’s oral argument represents the first time that Washington’s highest court will consider whether the WVRA is constitutional: “[I]ts decision, if it upholds the WVRA (as I fully expect it will), could usher in a period of transition away from discriminatory practices in local elections, through the mechanisms provided for in the WVRA.”

You can listen to a live stream of tomorrow’s oral argument here.