North Carolina Wants People To Pay to Vote

On April 28, 2023, the North Carolina Supreme Court upheld the state’s felony disenfranchisement law, originally enacted in 1877. The goal at the time was to “accomplish what the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited North Carolina from doing directly”: to disenfranchise Black men who had recently gained the right to vote.

Updated in the 1970s, the Tar Heel State’s policy strips voting rights from individuals with felony convictions up until the completion of their entire sentence, including probation, post-release or community supervision. One of the most egregious parts of the law requires individuals to pay all fees, fines or other debts related to convictions before they are released from probation.

In 2019, various civil rights and community groups challenged North Carolina’s felony disenfranchisement statute and in March 2022, a trial court permanently struck down the entire law. The court specifically found that the “pay-to-vote” scheme violated a state constitutional guarantee that “no property qualification shall affect the right to vote or hold office.” Late last month, the North Carolina Supreme Court, with its newly elected GOP majority, reversed the trial court’s decision, finding no issue with conditioning voting rights upon one’s ability to pay.

Daryl Atkinson, co-director of Forward Justice and a lead attorney in the North Carolina lawsuit, told Democracy Docket: “In no democracy, should the amount of money you have in your pocket be a determiner of whether you have a civic voice.” But it does, and not just in North Carolina. Modern day poll taxes exemplify how laws protecting the right to vote too often fail to apply to people with past felony convictions.

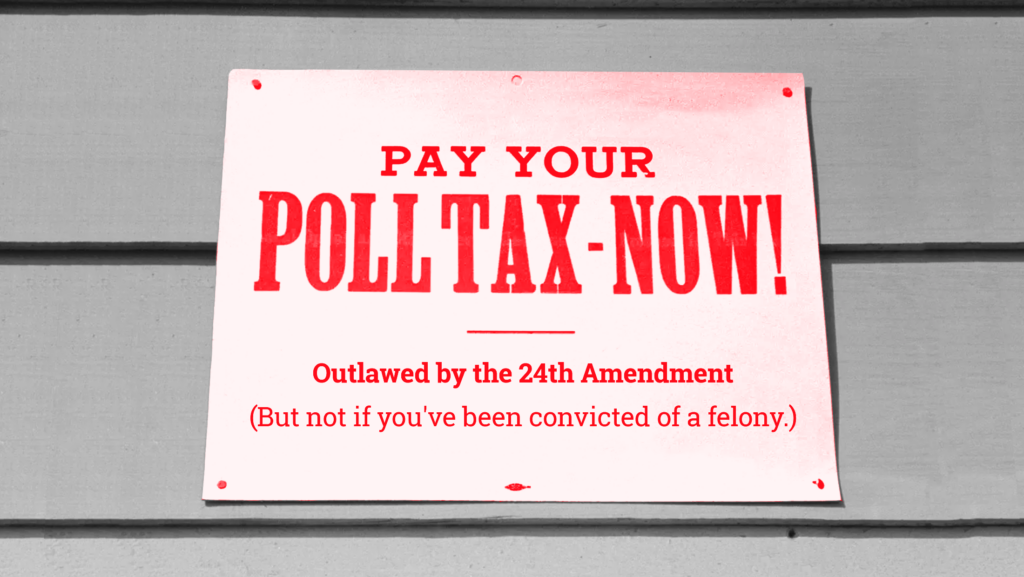

The United States has a dark history of wealth-based disenfranchisement until it was outlawed in the 1960s.

After the end of Reconstruction in 1877, southern states were laser focused on preventing newly enfranchised Black men from voting. Among the laws specifically designed with this goal in mind, poll taxes — flat taxes levied per person, regardless of income — are one of the most well known. It wasn’t until the post-Reconstruction period that lawmakers started to implement poll taxes as a prerequisite for voting. Eventually, 11 southern states would do so. For years, courts largely looked the other way from, or actively endorsed, these disenfranchising schemes.

That was until the adoption of the 24th Amendment in 1964, which prohibited poll taxes in federal elections. A resident in Virginia, one of five states that continued to impose poll taxes to vote in state elections, challenged Virginia’s law under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, leading the U.S. Supreme Court to overrule its own 1937 decision and deem Virginia’s poll tax for state elections unconstitutional.

“For, to repeat, wealth or fee paying has, in our view, no relation to voting qualifications; the right to vote is too precious, too fundamental to be so burdened or conditioned,” reads Justice William Douglas’ majority opinion in the case, Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections (1966).

Today, a handful of states still condition voting rights on payment for people with past felony convictions.

If there’s a constitutional amendment, the federal Voting Rights Act and a Supreme Court case to protect against wealth-based voting qualifications, how is it possible that in 2023 some states still condition rights restoration on money? People caught up in the carceral system — a population that skews poor and nonwhite — are treated uniquely in the voting sphere. Several states have explicit or implicit requirements to pay all fees and fines after a felony conviction before their rights can be restored.

Florida has the most startling and well-known example of a wealth-based disenfranchisement scheme. In 2018, Floridians overwhelmingly supported a constitutional amendment restoring voting rights to most people upon release from incarceration. Despite over 64% of voters in favor of expanding rights restoration, the Florida Legislature and Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) pushed back. Senate Bill 7066, signed less than a year later, required formerly incarcerated individuals to pay all fees and fines related to their felony convictions before they could register to vote, effectively disqualifying over 750,000 otherwise eligible Florida voters, according to the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition.

Legal debts can range from a few hundred to tens of thousands of dollars, burdening those trying to reestablish their lives post-incarceration. “I have no idea what I have to pay,” one formerly incarcerated Florida resident told the New York Times. “I just know every time I reach out, it’s a different number, and it’s increasing.”

This new “pay-to-vote” requirement was immediately challenged in court: In May 2020, a district court ruled that the Florida law violated the 24th Amendment, among others. However, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed that ruling and reinstated the modern day poll tax.

Florida is not alone: Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, South Dakota and Tennessee explicitly require the repayment of court fines and fees before re-enfranchisement. Several other states mandate some form of payment of legal debt before release from probation, including North Carolina.

Laws protecting the right to vote too often fail to apply to formerly incarcerated individuals.

In 1974, the Supreme Court determined that felony disenfranchisement, as an overarching concept, was constitutional. The Court pointed to Section 2 of the 14th Amendment, which forbids the abridgment of voting rights “except for participation in rebellion, or other crime,” effectively placing people convicted of crimes in a separate category in regards to an otherwise fundamental right. (The decision left open the possibility for certain laws to be challenged on the basis of unequal enforcement or racially discriminatory intent.)

The recent ruling in North Carolina leaned into this sentiment that people convicted of crimes can be treated differently: “[I]t is not unconstitutional merely to deny the vote to individuals who have no legal right to vote,” North Carolina Supreme Court Justice Trey Allen summarized. In a catch-22 of disenfranchisement, the court decided that because people with felony convictions “have no state constitutional right to vote,” they can’t be impacted by the imposition of property qualifications on the right to vote.

Additionally, the North Carolina Supreme Court heavily relied on the 11th Circuit’s ruling in the Florida case that found that “Florida’s felon re-enfranchisement laws were reasonably related to legitimate government interests.” In the North Carolina context, the court’s majority suggested that maybe the North Carolina Legislature believed that “felons who pay their court costs, fines, or restitution are more likely than other felons to vote responsibly” or that the rule was a useful incentive for the state to recuperate court costs.

“We are not attacking the fee and fine regime that states levy against people; that’s a lawsuit for another day,” Atkinson explained on a recent podcast with Democracy Docket discussing the North Carolina felony disenfranchisement challenge. “What we are attacking is tethering the right to vote to the payment of those fees, fines and cost. That’s what we need to be able to decouple…We may decide that as a society, that’s an appropriate, additional punitive sanction, but tethering civic rights to that has no rational meaning. It makes no sense because you are simply premising the right on wealth, plain and simple.”