The Power of State Constitutions

In 2019, in Rucho v. Common Cause, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it didn’t have the authority nor the ability to resolve partisan gerrymandering claims when redistricting maps are drawn to favor one political party over another. Instead, the five justices in the majority sent this question back to the states to decide. Now, the Supreme Court will hear a case next term that threatens to remove that authority from state courts, just three years later.

In Moore v. Harper, the Supreme Court will review the independent state legislature (ISL) theory, a radical interpretation of the U.S. Constitution that would allow state legislatures to set federal election rules and draw congressional maps without oversight from state courts and their application of state constitutions. In today’s piece, we review the history of state constitutions, exploring how they sometimes confer additional rights not outlined in the U.S. Constitution — a layer of protection that is threatened by Moore.

Every state has its own constitution. These documents often grant rights beyond the federal Constitution.

Between 1787 and 1790, the 13 original states ratified the U.S. Constitution. The remaining 37 states joined the Union later under the authority of the Constitution’s Admissions Clause, which permits new states to be admitted by an act of Congress. In some instances, California for example, Congress simply passed a bill declaring a new state. More often, Congress passed an enabling act that authorized the population of a territory to convene a constitutional convention. If the adopted state constitution satisfied the enabling act, the state would be admitted to the Union. Congress sometimes imposed specific requirements for those new state constitutions, such as bans on slavery or polygamy. The Constitution’s Guarantee Clause additionally requires all states to have a “Republican Form of Government” where the people govern through elections.

While state constitutions cannot conflict with the national document, states are able to outline or clarify rights that go further than those in the federal Constitution. The average length of a state constitution is about 39,000 words, compared to the U.S. Constitution with less than 8,000.

In the sphere of voting rights, surprisingly, the Constitution does not explicitly grant a right to vote. Instead, the right is implied through various amendments on how the government cannot deny that right to different groups of citizens. In contrast, state constitutions are strikingly uniform in explicitly granting the right to vote; 49 states include who “shall be qualified to vote,” is “entitled to vote” or is a “qualified elector.” Only in the Arizona Constitution is the language flipped, stating who does not have the right to vote.

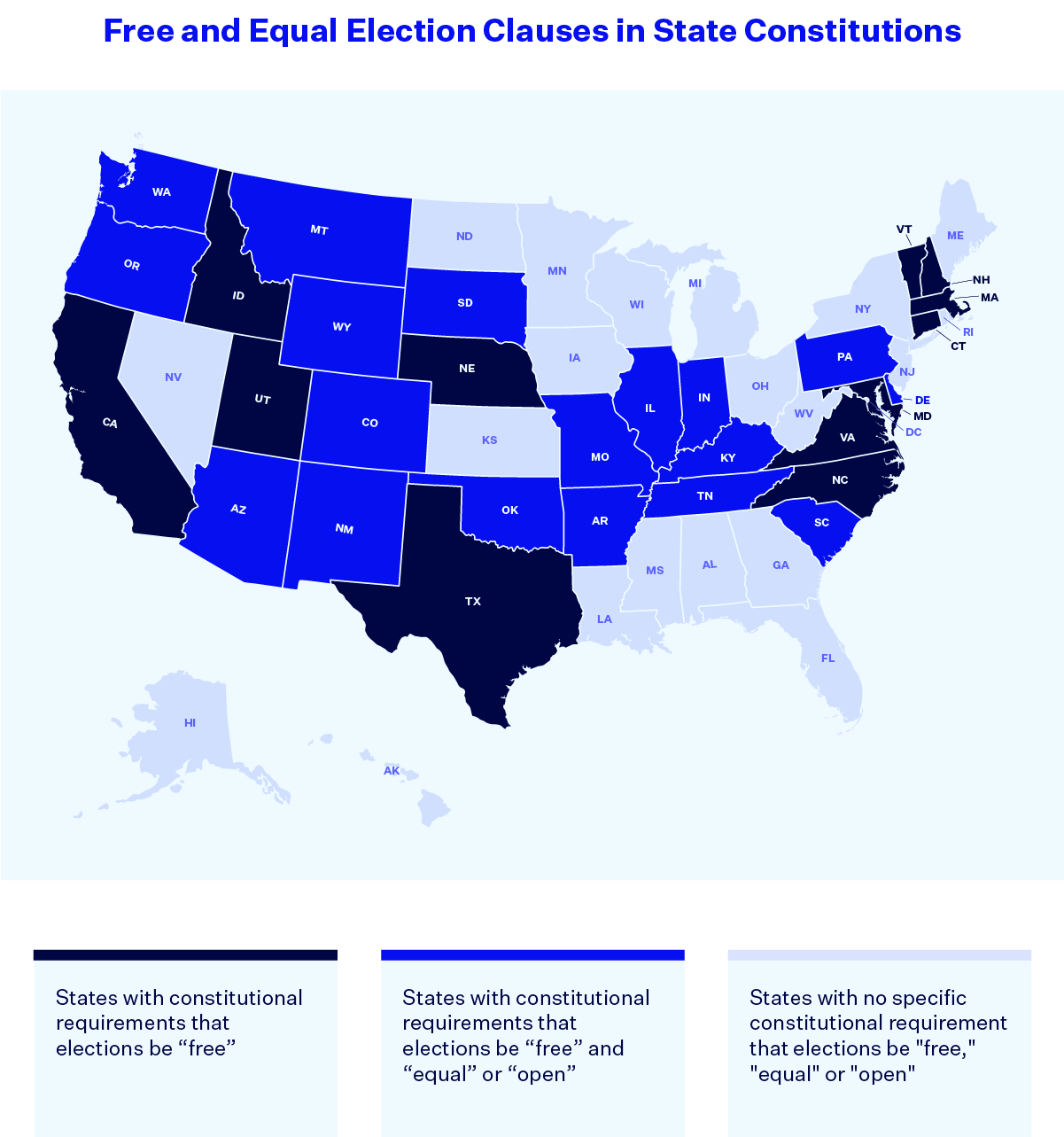

Thirty state constitutions require elections to be “free.”

Thirty state constitutions contain additional voting protections — 12 states have some form of constitutional requirement that elections be “free” and 18 states go even further, requiring that elections be “free” and “equal” or “open.”

State courts have interpreted state constitutions to protect against unfair districts.

“Our conclusion does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering. Nor does our conclusion condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in his majority opinion in Rucho v. Common Cause in 2019. “Provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply.”

When Rucho closed the door on federal review of partisan gerrymandering, there remained optimism that state constitutions could provide important protections in this area. The free elections clauses in state constitutions were successfully used to strike down gerrymandered maps in Pennsylvania in 2018 before Rucho and North Carolina immediately after the case. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court concluded that its state’s free and equal elections clause “mandates that all voters have an equal opportunity to translate their votes into representation.”

In the post-2020 redistricting cycle, litigants once again struck down North Carolina’s partisan gerrymanders under the state constitution. Lawsuits claiming relief under free elections clauses were also filed against new maps in Arkansas, Kentucky, Maryland and Utah. Additionally, lawsuits were filed in Florida, New York and Ohio under even more specific anti-gerrymandering state constitutional provisions. (In all three states, these provisions were added to their state constitutions within the past decade via citizen-initiated constitutional amendments.)

In contrast to the federal Constitution, state constitutions are significantly more explicit in conferring the right to vote and include additional protections for free, equal and open elections. These provisions have been particularly effective in the sphere of redistricting and partisan gerrymandering.

For years, state judges have played an important role in defending democracy by interpreting their constitutions within a state-specific context and sometimes extending protections beyond federal jurisprudence. With Moore and the ISL theory before the U.S. Supreme Court, this is now all at risk.