Alaska’s Supreme Court Prohibited Partisan Gerrymandering. These States Have Too

On Friday, April 21, the Alaska Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling: Partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional under the Alaska Constitution. The decision, which emerged out of a consolidated lawsuit challenging the Last Frontier’s legislative maps drawn with 2020 census data, makes Alaska the latest state to offer constitutional protections against unfair maps.

Nearly four years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019) that federal courts don’t have the authority nor the ability to resolve questions of partisan gerrymandering, the outcome when redistricting maps are drawn to favor one political party over another. “Our conclusion does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering. Nor does our conclusion condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the Rucho majority opinion. “Provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply.”

In the aftermath of Rucho, state courts and state constitutions have been put to the test: Can they protect voters from politicians who warp lines to their partisan advantage? For some time, we could only point to Florida, North Carolina and Pennsylvania as states where courts have ruled against partisan gerrymandering. Now, after the 2020 redistricting cycle, there are more maps, more lawsuits and slowly but surely, more rulings.

In at least six states, the state’s highest courts have confirmed that they have the authority to address partisan gerrymandering. At least one other state, Kansas, has rejected partisan gerrymandering as a nonjusticiable issue under the state constitution, meaning it falls outside the scope of a court to decide. Several other cases are creeping up through the state court system and will likely see final rulings within the year. The rulings are rooted within a range of different provisions, from general constitutional protections to specific prohibitions against unfair map drawing.

In at least six states, state Supreme Courts have ruled that partisan gerrymandering is justiciable and violates their state constitutions.

In 2018, a year before Rucho, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court concluded that its state’s Free and Equal Elections Clause “mandates that all voters have an equal opportunity to translate their votes into representation.” The decision struck down the Keystone State’s 2011 congressional map that drew 13 solid Republican districts of the total 18 districts, despite a near evenly split statewide vote.

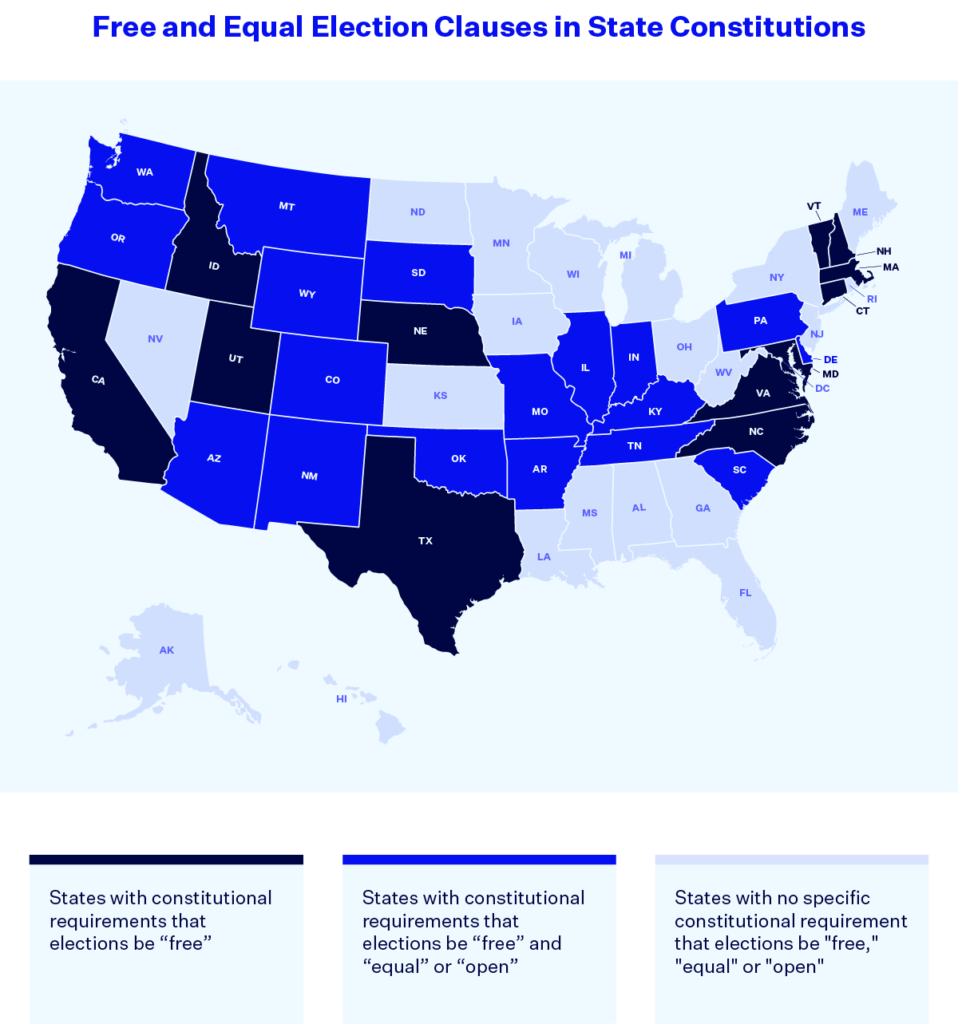

The Pennsylvania ruling leaned into the state’s guarantee of an equal opportunity to vote. In 30 states, including Pennsylvania, the state constitution contains some form of requirement that elections be “free,” “equal” or “open,” an additional protection that has no federal counterpart in the U.S. Constitution.

The Rucho case emerged from North Carolina, but just months after the U.S. Supreme Court shut the door on federal review in June 2019, a state court in Wake County struck down the North Carolina state House and Senate maps as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders under several different clauses in the North Carolina Constitution. The judge noted that “North Carolina’s Equal Protection Clause provides greater protection for voting rights than federal equal protection provisions.”

After the release of 2020 census data and subsequent line drawing, a partisan gerrymandering lawsuit wound up before the North Carolina Supreme Court. In February 2022, the state’s highest court ruled that partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable under the North Carolina Constitution. “Our dissenting colleagues have overlooked the fundamental reality of this case,” the majority wrote in an extensive opinion. “Rather than stepping outside of our role as judicial officers and into the policymaking realm, here we are carrying out the most fundamental of our sacred duties: protecting the constitutional rights of the people of North Carolina from overreach by the General Assembly.” (This decision is now at risk due to the court rehearing the case after party control of the court shifted from Democrat to Republican in the 2022 midterm elections.)

Now, Alaska joins the list as the third state Supreme Court to find that a broad state constitutional provision bars partisan gerrymandering. In contrast to North Carolina and Pennsylvania, which rely at least partly on free election clauses, Alaska’s ruling was rooted within the state’s Equal Protection Clause. “Considering the Constitutional Convention minutes, the 1999 amendments’ legislative history, and our case law, we expressly recognize that partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional under the Alaska Constitution,” the Alaska Supreme Court ruled last week.

“Both of these decisions [Pennsylvania in 2018 and Alaska in 2023] emphasized noncompliance with nonpartisan requirements and didn’t fixate on empirical evidence of partisanship,” law professor and redistricting expert Nicholas Stephanopoulos wrote in reaction to the recent ruling. “This approach is appealing because it demands less empirical sophistication on the part of courts, it builds on precedent (especially in Alaska), and it doesn’t force courts to accuse other institutional actors of partisanship.” However, Stephanopoulos tempered expectations: “On the other hand, adept gerrymanderers may be able to achieve their partisan aims while still designing maps that reasonably satisfy criteria.”

The other bucket of states that have outlawed partisan gerrymandering rely on explicit bans on unfair map drawing. Over the past decade, several states have adopted redistricting reforms, often via citizen-initiated constitutional amendments, which include prohibitions on partisan gerrymandering.

So far, at least three state Supreme Courts have ruled on these specific constitutional provisions: Florida, New York and Ohio. The provisions outline that districts “may not be drawn to favor or disfavor an incumbent or political party” or another variation. Notably, before the explicit anti-gerrymandering provisions were added, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that its constitution did not “mandate political neutrality” in legislative redistricting.

In May 2022, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering is nonjusticiable under its state constitution.

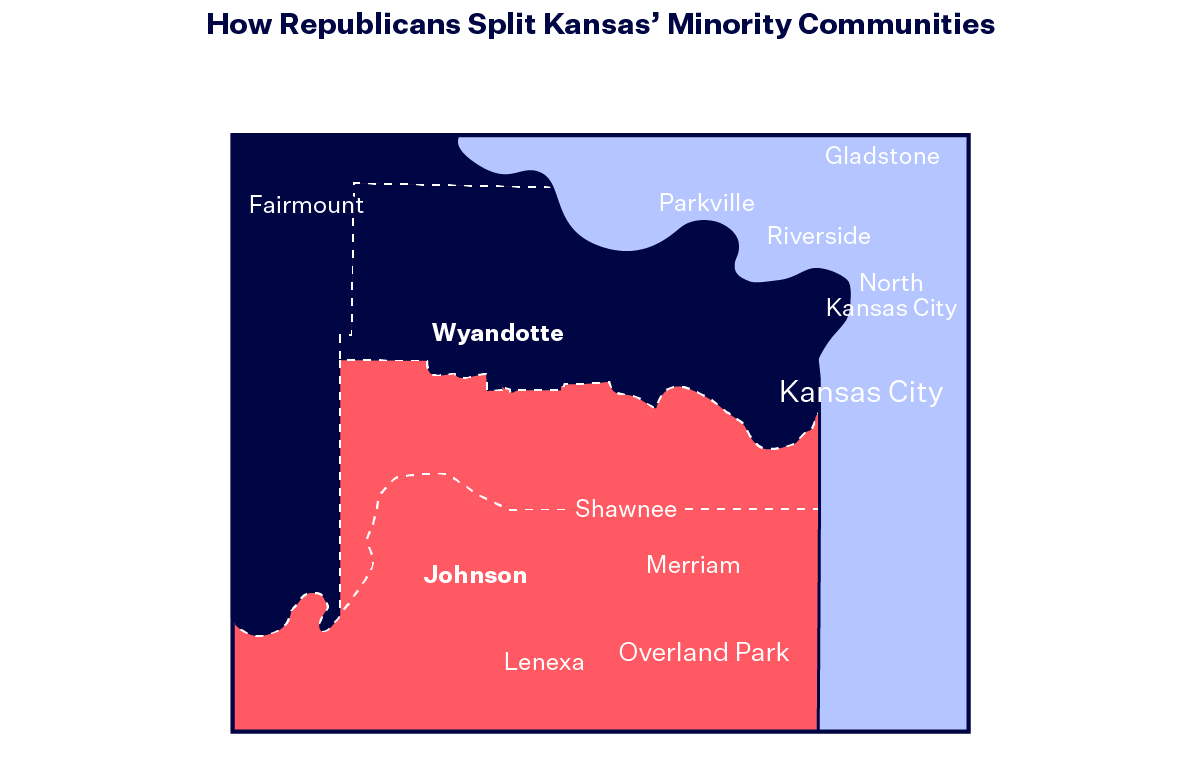

Overriding the veto of Gov. Laura Kelly (D), the Republican-controlled Kansas Legislature enacted a congressional map in early 2022 that split Wyandotte and Douglas counties, the state’s two Democratic strongholds and heavily minority counties. The resulting map was expected to maximize GOP advantage with three Republican districts and one highly competitive district. (The state’s lone Democratic representative, Sharice Davids, exceeded expectations in her reelection on Election Day 2022.)

In May 2022, the Kansas Supreme Court reversed a lower court order that struck down the congressional map. In its opinion, a majority of the court found that the partisan gerrymandering is a nonjusticiable political question that’s unsuitable for Kansas courts to rule on.

Since the Kansas Constitution does not contain a clear ban on partisanship in redistricting, the court held that it cannot decide such claims “at least until such a time as the Legislature or the people of Kansas choose to codify such a standard into law.”

“We find the reasoning of Rucho persuasive and expressly adopt it here. But that does not end the inquiry at the state level,” the court held. In addition to the potential to adopt clear redistricting standards, the Kansas court distinguished itself from states like North Carolina, where courts have “discerned clear standards in their case precedent” despite no constitutional anti-gerrymandering mandate.

The Kansas Supreme Court then went on to address, and reject, race-based claims in the same lawsuit.

Trial courts in Maryland, Kentucky and New Hampshire have weighed in and several other lawsuits remain ongoing.

In the most recent redistricting cycle, there have been nearly 30 lawsuits across 13 states challenging maps for partisan gerrymandering. In four states — Florida, New York, Ohio and Oregon — the lawsuits referred to specific anti-gerrymandering provisions outlined in state laws or state constitutions. In eight states — Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Utah — the lawsuits invoked broader protections within state constitutions. (One lawsuit in Michigan alleged that partisan gerrymandering violated both specific and broad provisions.)

While some lawsuits have been resolved, others remain open and ongoing. In 2022, district courts in three states ruled on partisan gerrymandering using broad constitutional provisions.

A Maryland judge concluded that the “jurisprudence in Maryland indicates that the Free Elections Clause has been broadly interpreted to apply to legislation that infringes upon the right of political participation by citizens of the State.” While that judge found that Maryland’s newly enacted congressional map violated several provisions of the Maryland Constitution, including the Equal Protection Clause and Free Speech Article, appeals of the decision were dismissed before any higher state court could weigh in.

Unlike Mayland, in finding that Kentucky’s state House and congressional maps were constitutional, a judge noted that “the Kentucky Constitution does not explicitly prohibit the General Assembly from making partisan considerations during the apportionment process.” The plaintiffs sought relief under a Free and Equal Election Clause, among others. On March 29, 2023, the Kentucky Supreme Court took over the appeal and litigation is ongoing.

In granting a motion to dismiss, a New Hampshire judge rejected claims in a lawsuit that partisan gerrymandering violated the New Hampshire constitution’s requirement that “[a]ll elections are to be free, and every inhabitant of the state of 18 years and upwards shall have an equal right to vote in any election.” Citing both Rucho and the Kansas Supreme Court’s order, the judge held that political gerrymandering was nonjusticiable under the New Hampshire Constitution unless it included additional criteria “explicitly provid[ing] those requirements.” The New Hampshire Supreme Court will hear oral argument on the plaintiffs’ appeal on May 11, 2023.

In addition to the appeals in Kentucky and New Hampshire, we are expecting rulings in several other partisan gerrymandering cases. Notably, New Mexico and Utah await decisions where no court has yet touched upon the justiciability of the issue under their state constitutions.

In New Mexico, the state’s highest court heard oral argument in January and then requested additional briefing on the one particular question. It’s the same question that almost all state courts will likely ask themselves: “Does [our state constitution] provide greater protection than the United States Constitution against partisan gerrymandering?”