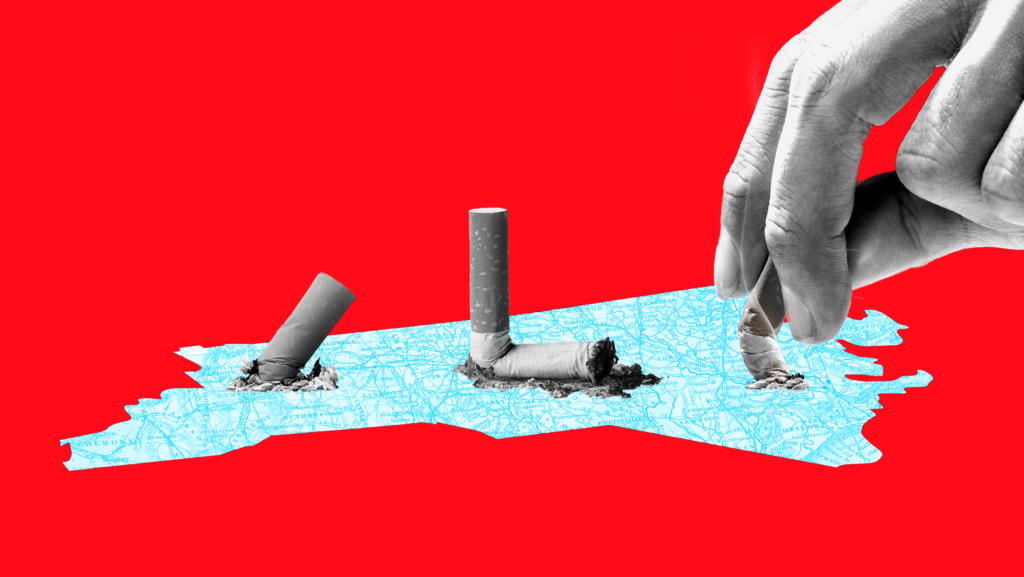

The North Carolina Supreme Court’s Three-Part Attack on Democracy

On a single day, Friday, April 28, 2023, the North Carolina Supreme Court wreaked havoc on voting rights. The court dropped three major decisions, all harmful outcomes for voters and democracy.

Two of the decisions — Harper v. Hall and Holmes v. Moore — were from cases that were decided just a few months ago by the same court. To be clear: There has been no change in the facts or law since last year. The only change has been the composition of the court, since Republicans gained a 5-2 majority on the court in the 2022 midterm elections. (North Carolina Supreme Court justices are elected in partisan match-ups.)

In a simple but cynical gambit, Republican lawmakers asked for a redo after the court flipped red. They did not like the pro-voter outcomes with the previously Democratic-led court, so they requested and were granted rehearing.

In one fell swoop last Friday, the court’s new Republican majority permitted extreme partisan gerrymanders, reinstated a restrictive photo ID law and upheld the state’s felony disenfranchisement law. While the felony disenfranchisement case followed a typical journey through the state court system, the other two opinions emerged from rehearings that represent Republicans’ disregard for judicial norms. In all three decisions, five white Republican justices ruled against North Carolina voters and in favor of conservative politicians. The two Black justices on the court, Justices Anita Earls and Michael Morgan, dissented in all three cases.

Harper v. Hall: The North Carolina Supreme Court greenlit partisan gerrymandering.

In Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that federal courts don’t have the authority nor the ability to resolve questions of partisan gerrymandering, when politicians draw maps to favor one political party over another. It was a major loss for fair maps, but in the years since, voters have turned to state courts and state constitutions to provide additional protections.

For decades, North Carolina was the poster child for partisan gerrymandering. After the release of 2020 census data and subsequent line drawing, a redistricting lawsuit ultimately wound up before the North Carolina Supreme Court, then with a 4-3 Democratic majority. In February 2022, the state’s highest court ruled that partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable under the North Carolina Constitution, meaning that the question falls within the scope of a court to decide. At that time, the Tar Heel State’s highest court struck down the new congressional, state House and state Senate maps for being Republican partisan gerrymanders. In December 2022, the court once again utilized the same reasoning to strike down one redrawn map.

Pro-democracy groups celebrated this as a huge win for voters. The state’s highest court ruled that certain provisions in the North Carolina Constitution — namely the Free Elections and Equal Protection clauses — contained protections that went further than the federal U.S. Constitution and did in fact protect voters from unfair political gerrymandering.

By Marc Elias, founder of Democracy Docket and a voting rights lawyer.

After an unprecedented rehearing in March 2023, the new Republican majority overturned that decision last Friday. In a decision authored by Chief Justice Paul Newby, the court ruled that the North Carolina Supreme Court got it wrong last year and instead held that partisan gerrymandering claims are actually not justiciable under the state constitution. “[C]reating partisan redistricting standards is rife with policy decisions. Policy decisions belong to the legislative branch, not the judiciary,” Newby wrote, citing Rucho as “insightful and persuasive.”

Newby chronicled the historical context of the state’s Free Elections Clause to conclude that “free elections” only refers to “elections free from interference and intimidation,” before explaining why other state constitutional provisions also do not apply to redistricting.

“Recently, this Court has strayed from this historic method of interpretation to one where the majority of justices insert their own opinions and effectively rewrite the constitution,” Newby concluded, justifying his decision to overrule a prior decision.

As a result of the ruling, the state Legislature will have full authority to redraw all of the state’s electoral maps this summer. The Republican-controlled North Carolina Legislature has shown a repeated desire to draw extreme partisan gerrymanders and the state Supreme Court just gave it the green light to do so without any constraints.

To further complicate matters, this state-level redistricting case ultimately morphed into Moore v. Harper, the U.S. Supreme Court case seeking review of the radical independent state legislature theory. Friday’s ruling renders that case before the Supreme Court effectively moot, though there are several ways the nation’s highest court could still rule.

Find all the court documents for Harper v. Hall — and its related case Moore v. Harper — here.

Holmes v. Moore: The North Carolina Supreme Court reinstated a strict photo ID law.

In the second decision overruling itself, the North Carolina Supreme Court reversed a decision from December 2022, less than five months ago.

Last December, the court blocked Senate Bill 824, a suppressive voting law that narrowed the list of qualifying photo IDs acceptable for voting in the state. In (what we thought was) the final decision, the then-Democratic-controlled court ruled that the voter ID law violated the Equal Protection Clause of the state constitution because it was enacted with racially discriminatory intent. After extensive fact-finding, the court relied on the strong evidence of a disparate impact on Black North Carolinians and the legislative history to show that the Legislature intended to target Black voters.

In Friday’s decision reinstating S.B. 824, the court’s Republican majority held that the plaintiffs “failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that S.B. 824 was enacted with discriminatory intent or that the law actually produces a meaningful disparate impact along racial lines.” This ruling stands in stark contrast to the December ruling that leaned into the evidence considered by the trial court.

Justice Phil Berger Jr. wrote on behalf of the conservative majority, calling the claim that the voter ID law discriminates on the basis of race in the violation of North Carolina’s Equal Protection Clause “speculation and innuendo.” Berger instead relied on several federal cases for guidance.

“The people of North Carolina overwhelmingly support voter identification and other efforts to promote greater integrity and confidence in our elections,” Berger stated, before suggesting that his ruling was exemplary of judicial restraint, an ironic pontification given that he just overturned recent precedent set by the very court on which he sits.

Find all the court documents for Holmes v. Moore here.

Community Success Initiative v. Moore: The North Carolina Supreme Court upheld the state’s felony disenfranchisement law.

Overturning its own decisions when it comes to unfair maps and restrictive voting laws wasn’t enough. The North Carolina Supreme Court decided to revoke voting rights from over 56,000 North Carolinians, upholding the state’s felony disenfranchisement law.

North Carolina originally enacted felony disenfranchisement in an 1877 constitutional amendment. The goal was to “accomplish what the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited North Carolina from doing directly,” to disenfranchise Black men who had recently gained the right to vote. The law implementing this constitutional amendment, as updated in the 1970s, strips voting rights from individuals with felony convictions until the completion of their entire sentence, including probation, post-release supervision or community supervision. Release from probation requires individuals to pay various legal and court fees, so re-enfranchisement is contingent on an individual’s ability to pay.

In March 2022, a trial court permanently struck down the felony disenfranchisement rule for violating the Equal Protection, Free Elections and Property Qualifications clauses of the North Carolina Constitution. The trial court noted that the law “interferes with the exercise of the fundamental right of voting and operates to disadvantage a suspect class.” The “pay-to-vote” scheme — which conditions voting eligibility upon repayment of court fees — was found to violate the Property Qualification Clause that states that “no property qualification shall affect the right to vote or hold office.” The immediate impact of that decision restored voting rights to over 56,000 North Carolinians.

Now, the North Carolina Supreme Court reversed that decision. The Republican majority pointed to the updates made to the felony disenfranchisement statute in the early 1970s and determined that “the available evidence does not show that racial discrimination inspired the General Assembly” at that time and that the trial court failed to “apply the presumption of legislative good faith to the General Assembly’s 1971 enactment of a new section.” In contrast, the trial court had ruled that “[t]he legislature cannot purge through the mere passage of time an impermissibly racially discriminatory intent.”

The Supreme Court also rejected the trial court’s evidence of disparate racial impact of the law, adding that there was no reason to believe that disenfranchisement occurs for “African American felons at a rate that differs from the re-enfranchisement rate for white felons.” The court ignored the disparate impact of the criminal legal system in North Carolina that leads to felony convictions in the first place.

Additionally, the North Carolina Supreme Court found no issue with the requirement that all fees, fines or other debts related to convictions be paid before release from probation. The court cited an 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruling that upheld Florida’s payment-based re-enfranchisement laws. In justifying possible government interests, the court suggested that maybe the North Carolina Legislature believed that “felons who pay their court costs, fines, or restitution are more likely than other felons to vote responsibly.” In regards to the Property Qualifications and Free Elections clauses, the court summarized its reasoning: “[I]t is not unconstitutional merely to deny the vote to individuals who have no legal right to vote.”

Although Black people comprise 21% of North Carolina’s voting-age population, they represent over 42% of those stripped of the right to vote under current statute. For Black men specifically, they constitute only 9.2% of the voting age population, but 36.6% of those disenfranchised. Additionally, North Carolina remains one of only a few states that conditions voting rights on the ability to pay, in what many consider a “modern day poll tax.”

Find all the court documents for Community Success Initiative v. Moore here.

In powerful dissents, Justices Anita Earls and Michael Morgan called out their colleagues for the brazen reversal of recent decisions.

“The five justices which constitute the majority here have emboldened themselves to infuse partisan politics brazenly into the outcome of the present case,” Morgan wrote in the Holmes dissent. “This majority’s extraordinarily rare allowance of a petition for rehearing in this case, mere weeks after this newly minted majority was positioned on this Court and mere months after this case was already decided by a previous composition of members of this Court, spoke volumes.”

Earls wrote the dissenting opinions in both Harper and Community Success Initiative. She cited her previous writing to summarize the impact of these rulings and the unprecedented nature of overturning two recent cases: “[O]ur decisions are fleeting, and our precedent is only as enduring as the terms of the justices who sit on the bench.”