Voter Registration Should be Simple. Red States Are Making It Harder.

It was a shockingly fast turnaround, even by politicians’ standards. When asked this past January about ERIC — a multi state collaboration that helps election officials improve the accuracy of their voter rolls and increase access to voter registration — Iowa Secretary of State Paul Pate (R) called the effort “a godsend.” Come March, Pate announced on Twitter that he intends to withdraw Iowa’s membership from ERIC entirely.

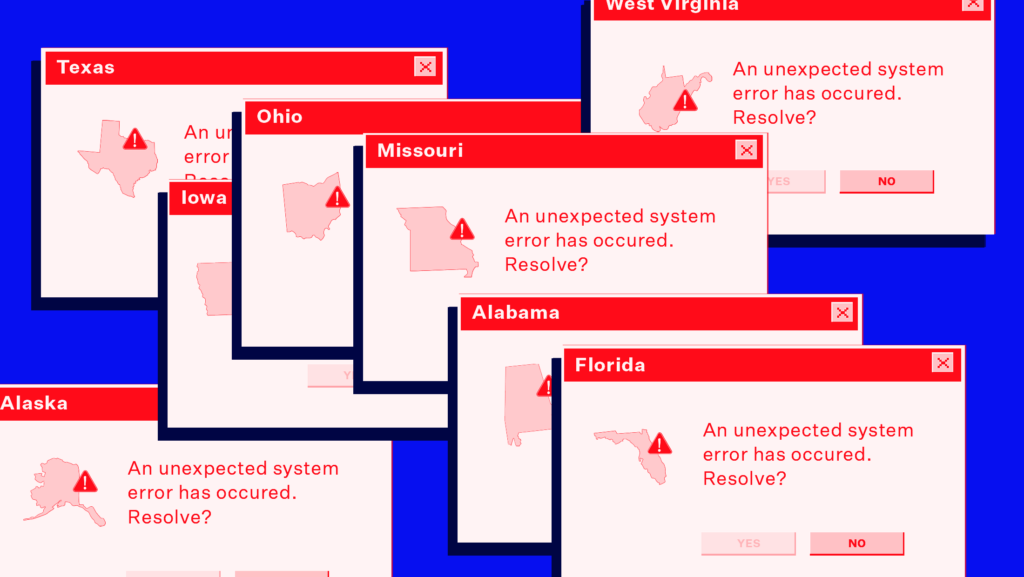

Pate is not alone. ERIC is experiencing a veritable exodus of Republican-led states. Alabama and Louisiana left in 2022. Missouri, Florida and West Virginia withdrew last month. Ohio and Iowa are now following suit, and Alaska and Texas are reportedly considering leaving, too. The states that remain in ERIC are overwhelmingly Democratic — a striking change from a year ago, when the consortium was still one of few remaining bipartisan election institutions in the country.

Why are the Republicans jumping ship? They commonly cite two issues. The first is ERIC’s refusal to remove its founder, David Becker, from its board of directors. Republican officials claim Becker, a nonvoting member, is a Democratic operative. Frankly, this is nonsense. Becker has a long history of working with both Democratic and Republican leaders to improve and safeguard election administration. A recent letter signed by 24 current and former Republican state and local officials, including Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R), highlights Becker’s bipartisan credentials and dismisses the claims levied against him as “disinformation” pushed by “extremists.”

The second issue Republicans cite is particularly telling: they want ERIC to stop requiring them to conduct voter outreach. Under the current bylaws, member states must offer unregistered, eligible residents the chance to register at least once every two years, unless those individuals have already been contacted at their current address or have opted out of registration-related outreach. In a recent interview, Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft (R) described this voter outreach as “harassing people.”

When states simplify the voter registration process, everyone benefits.

Let’s be clear: offering people the opportunity to register to vote is not harassment, and calling it such is a cynical messaging strategy. Red-state politicians know what scholars have repeatedly found across dozens, if not hundreds, of studies: voter outreach dramatically benefits groups who have been systematically excluded from the political process — poor people, young adults and people of color.

In other words, the issue with reaching out to potential new registrants is that it sweeps up the exact individuals Republicans are loath to mobilize: left-leaning voters. Former President Donald Trump said as much when he took to social media in early March to call ERIC “the terrible Voter Registration System that ‘pumps the rolls’ for Democrats.”

It is not a coincidence that unregistered voters are disproportionately from socially disadvantaged groups. America’s unique approach to voter registration — one that puts the onus of registering on individuals, and not on the government — is now broadly understood as a means of increasing election security. But the original registration laws adopted in the late 1800s and early 1900s often served a second purpose, as described in detail by political historian Alexander Keyssar in his book The Right to Vote: preventing “undesirable” people from voting. Registration laws surely prevented at least some voter fraud, especially during an era dominated by political machines. But they also, in Keyssar’s words, “kept large numbers (probably millions) of eligible voters from the polls.”

Most other advanced democracies have taken a different approach to voter registration. In countries such as Canada, Australia and many European nations, the onus of voter registration is on the government, not the individual voter. In these countries, eligible citizens are automatically added to the voter rolls and can update their information easily online or through other means. This approach has been shown to increase voter turnout and reduce the administrative burden on individual voters. By contrast, the U.S. system places a significant burden on individual voters to navigate complex and often discriminatory voter registration policies.

When states simplify the voter registration process, everyone benefits. My research with Dr. Jake Grumbach has found that when states adopt same-day voter registration, allowing people to register and vote at the same time (rather than requiring people to register by an arbitrary deadline), turnout goes up for everyone, and especially for young people. In another analysis, we found that people who live in states with automatic voter registration laws — which proactively register eligible voters when they interact with certain government agencies — have meaningfully higher turnout than their counterparts in states without automatic registration. Again, the turnout boosts are largest for youth and low-income people.

These registration reforms generate a positive feedback loop. Once people register to vote, they become more likely to be contacted by political candidates and organizations — groups that often rely on “registered voters” lists to identify which people are most likely to vote. This contact makes these new registrants more likely to vote. It gets better: once they cast their ballots, first-time voters are more likely to participate in the future. The new voters no longer find the voting process so opaque or intimidating, their preferred candidates are more likely to win office and their elected leaders have a greater incentive to prioritize voters’ top issues. Government starts looking more familiar, responsive and relevant — and this makes people even more likely to vote next time.

This is what elections should look like: a virtuous cycle of political engagement and government responsiveness. But red-state leaders are not championing the registration reforms that would move our elections closer to this vision. They are doing the opposite — not only by withdrawing from ERIC, but also by publicly opposing reform and, even more concerningly, introducing new bills that make registration even more complicated and restrictive.

Since 2021, Arizona legislators have passed bills that prohibit same-day voter registration and automatic voter registration, as well as a bill asking the U.S. Election Assistance Commission to change the federal voter registration form to require documentary proof of citizenship. Florida has made it harder for voters to update their registration forms, now requiring a driver’s license or Social Security number in certain instances. Montana has stopped allowing voters to register on Election Day itself, only allowing same-day registration during the early voting period. In 2023 alone, 24 states have introduced 64 registration-focused bills that restrict voter access, according to the Voting Rights Lab.

As other developed nations with government-managed registration systems have demonstrated, we can retain the security benefits of registration while making the process far less cumbersome for individuals. As is so often the case in the field of election policy, the problem is not a lack of solutions; it is a lack of political will on the political right. State legislators should follow the lead of Colorado and Oregon by adopting robust automatic voter registration programs. They should learn from our allies abroad and develop an American approach to universal, government-driven voter registration. They should try to register every eligible voter — because in a just society, no one should be deprived of their vote due to red tape.

Instead, GOP leaders are intentionally imposing new barriers to the voter registration process. What a shame.

Charlotte Hill is the interim director of the Democracy Policy Initiative at UC Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy. As a contributor to Democracy Docket, Hill writes about how structural reforms impact American democracy.