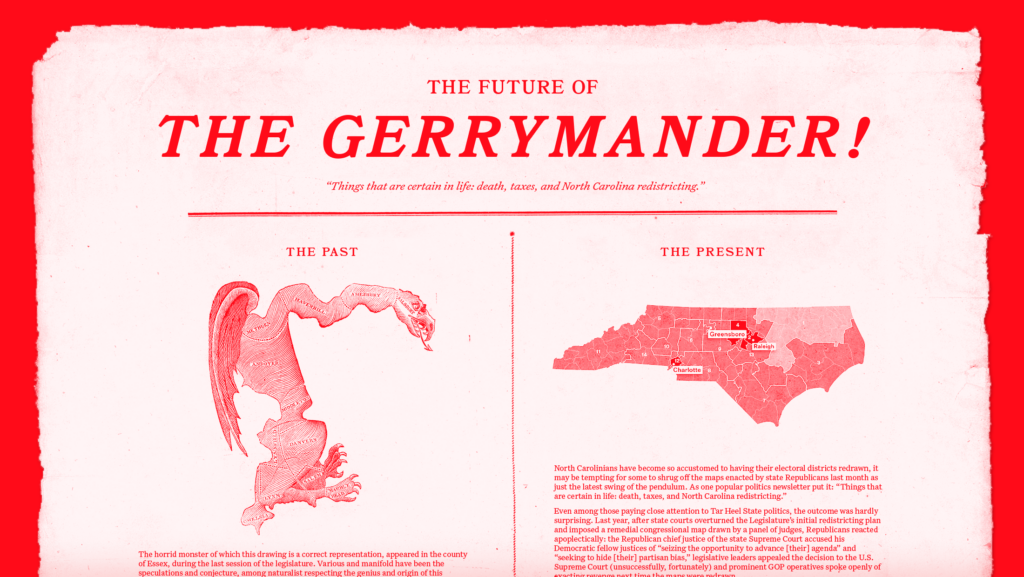

The Future of Partisan Gerrymandering in North Carolina

North Carolinians have become so accustomed to having their electoral districts redrawn, it may be tempting for some to shrug off the maps enacted by state Republicans last month as just the latest swing of the pendulum. As one politics newsletter put it: “Things that are certain in life: death, taxes, and North Carolina redistricting.”

Even among those paying close attention to Tar Heel State politics, the outcome was hardly surprising. Last year, after state courts overturned the legislature’s initial redistricting plan and imposed a remedial congressional map drawn by a panel of judges, Republicans reacted apoplectically: the Republican chief justice of the state Supreme Court accused his Democratic fellow justices of “seizing the opportunity to advance [their] agenda” and “seeking to hide [their] partisan bias,” legislative leaders appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court (unsuccessfully, fortunately) and prominent GOP operatives spoke openly of exacting revenge next time the maps were redrawn.

Then the 2022 election produced a Republican majority on the state Supreme Court, which moved swiftly to overturn the precedent the court had established just months before. No longer was extreme partisan gerrymandering a violation of North Carolinians’ constitutional rights; now it was “a political question that is nonjusticiable under the North Carolina Constitution.” The die was cast; the only question remaining was how far the Legislature would go.

We now know the answer. The new North Carolina maps are even worse than many feared, pursuing partisan advantage with greater audacity and precision than any gerrymander in recent history.

It’s not just that the congressional plan replaces a politically balanced map (7-7 in the current Congress) with one that will produce a Republican advantage of at least 10-4 in 2024, and likely 11-3 within a few years. It’s also the ruthless efficiency with which the plan achieves this feat.

The map packs Democratic and Black voters heavily into three urban districts in the Research Triangle and Charlotte, while spreading Republican voters evenly across the rest of the state. In redistricting terms, it maximizes wasted Democratic votes and minimizes wasted GOP votes.

In practical terms, it consigns Democrats to three “deep blue” seats while offering Republicans 10 seats that are just “red” enough to withstand serious competition — even in a wave election like 2018. The only truly competitive seat in the map — the 1st Congressional District, a sprawling rural district protected historically by the Voting Rights Act — is nominally Democratic but trending rapidly Republican.

The impact of the new maps — on state and national politics and on the lives of North Carolinians — will be profound.

This almost certainly makes North Carolina the most gerrymandered state in the country, at least on the basis of partisan proportionality. The popular Dave’s Redistricting website assigns the congressional map a proportionality score of zero out of 100 (yes, zero!). To put this number in perspective, Wisconsin and Illinois — two other leading contenders for the partisan gerrymandering crown — earn proportionality scores of 40 and 44, respectively.

The congressional plan also jettisons other “traditional” principles that have historically guided map drawers in North Carolina and elsewhere. In 2021, Republicans made much of their commitment to respecting municipal boundaries; the new map cracks eight of the state’s 10 largest cities into multiple districts. Voters in Greensboro — the state’s third-largest city, and the solidly Democratic anchor of the Piedmont Triad region — are fractured across three districts that voted for former President Donald Trump in 2020 by an average of 56.9%.

While the congressional map has received more attention, North Carolina’s new state legislative maps are nearly as extreme. According to an analysis by my Duke colleague Jonathan Mattingly, Republicans are heavily favored to retain their legislative “supermajorities” in both chambers — even, in some scenarios, if Democrats win a majority of the statewide vote. Importantly, Democrats retain a credible path to breaking the supermajority, and thus to sustaining the vetoes of future Democratic governors. But an outright Democratic majority within the decade? Forget about it.

The process that produced the maps was equally audacious. In 2021, legislative Republicans required all draft maps to be drawn in public view, invited members of the public to submit proposals and held more than a dozen public hearings across the state. The criteria they adopted explicitly banned political considerations and the use of election data. Sincere or not, these procedural reforms were important steps toward a more transparent and inclusive process.

This time around? Maps were drawn behind closed doors, there was no opportunity for the public to submit proposals and just three sparsely-attended public hearings were held. In place of the ban on political considerations, the adopted criteria proclaim that “politics and political considerations are inseparable from districting.” And for the chef’s kiss, Republicans tucked a provision into the state budget exempting redistricting records from state public records laws, greatly complicating efforts to challenge the maps in court.

The impact of the new maps — on state and national politics and on the lives of North Carolinians — will be profound. They are also the clearest sign yet that the United States has entered a new era of extreme partisan gerrymandering, characterized not by the elusive hope of a national solution but by chaotic and highly polarized action at the state level.

When the U.S. Supreme Court slammed the door on partisan gerrymandering claims in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), Chief Justice John Roberts reassured the nation that the decision “does not condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void.” But a void is exactly what Rucho created: in the four years since, some states have taken up the mantle of policing partisan gerrymandering, while others have become lawless enclaves for the unfettered pursuit of partisan advantage.

States like North Carolina — politically divided states that hold partisan judicial elections — are poised to veer wildly between these extremes, as courts’ constitutional interpretations fluctuate with their partisan composition.

A recent review of state-level partisan gerrymandering cases by several prominent redistricting scholars confirms this trend. In eight cases decided between the 2020 and 2022 elections, more than 95% of justices voted to overturn maps drawn by legislatures of the opposite party, while only a third voted to overturn maps drawn by their own party.

This points to a final, hard truth about the post-Rucho era: the courts will not save us from extreme partisan gerrymandering. Racial gerrymandering claims still offer limited recourse — including, perhaps, in North Carolina — and partisan claims should continue to be pursued where they are viable. But even where they are viable, legal victories will be ephemeral, always subject to reversal after the next election.

In these states, the only lasting recourse will be political: building power in state capitals and demanding change from lawmakers. This may sound trite in a place like North Carolina, given its current political configuration and the lack of a ballot initiative process. But Republicans came closer than many realize to enacting significant redistricting reform in early 2020, when it appeared Democrats were within reach of a legislative majority.

Our overriding goal must be to create comparable pressure for reform before 2030. This means investing strategically and substantially in state legislative races — starting today, not later in the decade. It means better messaging about the impact of extreme gerrymandering on voters’ daily lives. And it means being pragmatic about the shape of reform; independent redistricting commissions might be the gold standard, but they will not be feasible in every state.

None of this will be easy or cheap. But in this era of absentee federal courts and polarized state courts, it may be our only hope of ending partisan gerrymandering once and for all.

Asher D. Hildebrand is an associate professor at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy.