Redistricting Lawsuits Could Impact Control of Congress

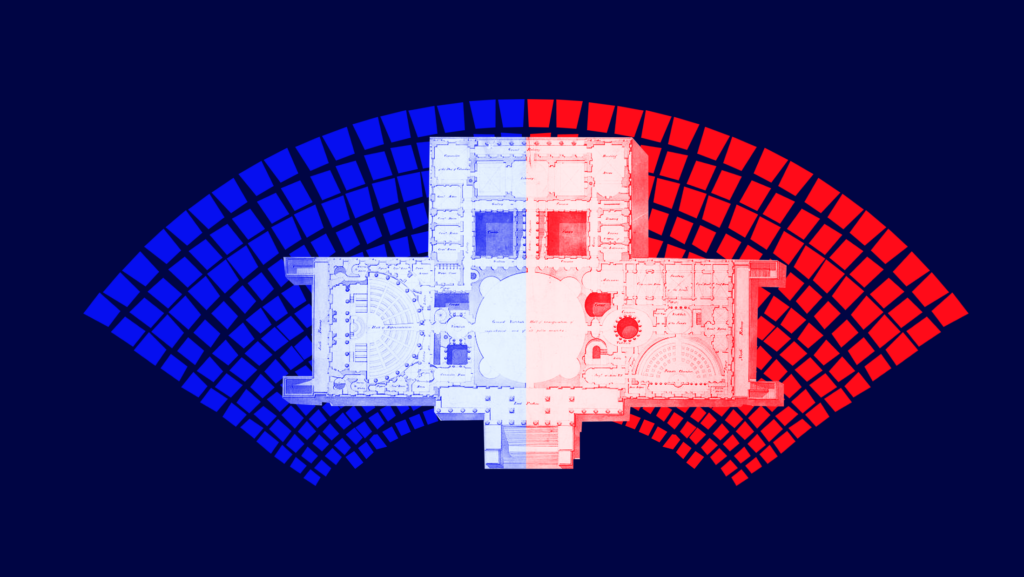

There is no factor that plays a more important role in partisan control of the U.S. House of Representatives than how congressional districts are drawn. While the purpose of the decennial redistricting process is to produce new maps that reflect changes in our country’s population, too often Republicans have used it to draw districts for political gain. In North Carolina alone, for example, the difference between a fair map and a Republican gerrymander could be four seats. In Florida, the difference could be five seats.

Racial gerrymandering or disregard for the Voting Rights Act (VRA) first and foremost disenfranchises minority voters. However, the propensity of many minorities, particularly Black voters, to support Democratic candidates means that those maps also affect the partisan balance of Congress. Courts have already ruled that Alabama and Louisiana should each have one additional Black-opportunity congressional district. These maps that were deemed illegal were in place for the 2022 elections while both decisions are currently on appeal. Georgia, South Carolina and Texas have active litigation over their racially biased maps, as well.

Given the political implications of redistricting, it is no surprise that there is a high volume of litigation that ensues over how district lines are drawn. A recent report from Democracy Docket reveals just how pervasive and important that litigation is to voters and control of Congress.

The new study finds that more than half of the states with multiple members of Congress have already faced redistricting litigation related to reapportionment after the 2020 census. According to the report, 70% of those cases remain ongoing in advance of 2024.

Since the release of 2020 census data, 46 lawsuits have challenged congressional maps across 22 states. This means that more than half of the states with multiple congressional districts were involved in redistricting litigation in the first two years of the redistricting cycle.

And the litigation is far from over. At the beginning of 2023, there were 32 ongoing cases that dispute congressional maps in 15 states. Significantly, some of the most contentious litigation is in states with the most congressional seats and greatest potential for partisan swings.

In fact, six of the 10 most populous states in the country still have litigation over their congressional maps: Florida, Georgia, New York, North Carolina, Ohio and Texas. Those states alone comprise 135 seats in Congress and litigation could easily account for a double-digit seat swing one way or the other. Remember that Republicans currently hold a very slim five-seat majority in Congress.

In addition, four states — Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, and Ohio — held elections in 2022 using maps that were ruled illegal but proximity to the elections required them to be used anyway. North Carolina’s map was struck down and replaced by a court-drawn map, but that map expired after 2022 and will need to be redrawn.

If it is close enough, the outcome of redistricting litigation may be decisive in who holds the speaker’s gavel on Jan. 3, 2025.

Sadly, racial discrimination continues to be the dominant theme in redistricting litigation. Fifty-two percent of all redistricting lawsuits contained a claim of racial discrimination or violation of the VRA. When compared to 32% of lawsuits that raised partisan gerrymandering claims, you can see that it is racial discrimination in voting and redistricting that remains the most pernicious ongoing problem in our democracy.

Chief Justice John Roberts may believe that “things have changed dramatically” since the adoption of the VRA in 1965, but the redistricting data doesn’t bear that out. Of the 15 states no longer subject to preclearance under the VRA — meaning they no longer had to seek federal approval before enacting maps — 10 saw lawsuits challenging their new district lines on racial grounds. More than two-thirds of the lawsuits raising racial challenges were brought in states that had previously been subject to preclearance.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s impact on this redistricting cycle is not complete. Two cases, one from Alabama and another from North Carolina, are pending before the Court and will be decided by July. The Alabama case addresses the application of the VRA to minority opportunity districts, while the North Carolina case involves the much-discussed independent state legislature theory. Both cases are almost certain to spark a wave of new redistricting cases later this year.

All of this reinforces two simple truths: First, while reapportionment may take place every 10 years, redistricting never stops — it happens throughout the decade. Second, courts play a larger role in determining district lines than any other institution, other than the legislatures themselves.

When former Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) took the speaker’s gavel in January 2021, she had a slim four-seat majority. Amidst the commentary about how Democrats won control, one critical reason was mostly missing from the discussion. Over the course of the previous decade, litigation that overturned unlawful, Republican-drawn maps netted House Democrats 10 seats in just four states: Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Virginia.

Whether it is Democrats or Republicans who benefit from litigation this cycle is yet to be seen. We also don’t know what future Supreme Court decisions will mean to new litigation that is not yet filed.

What we do know is that the Republican majority in Congress is only five seats. While the odds may favor Democrats’ chances to retake the majority in a presidential year, redistricting litigation has the greatest potential to alter the odds and change the outcome. If it is close enough, the outcome of redistricting litigation may be decisive in who holds the speaker’s gavel on Jan. 3, 2025.