Profiles in Cowardice

Shortly before John F. Kennedy’s book about courage in the U.S. Senate was released, he wrote an extraordinary essay in the New York Times Magazine that sought to explain the cross-pressures elected leaders feel as they formulate positions. If Profiles in Courage sought to demonstrate what political courage is, Kennedy’s essay offered insights into why some politicians display courage while others do not.

Kennedy rejected the romanticized notion that leaders demonstrate political courage solely because they “love the public better than themselves.” To the contrary, political courage often stems from politicians’ love of themselves because they “need to maintain their own respect for themselves” and “because their desire to maintain a reputation for integrity is stronger than their desire to maintain his office.”

As for those without any political courage, Kennedy concluded “It is when the politician loves neither the public good nor himself or when his love for himself is limited and is satisfied by the trappings of office, that the public interest is badly served.”

I was brought back to this delicate contradiction, of political courage relying on a commitment to democracy or a deep level of egotism mixed with self-preservation, while working through Texas’s failed bid to the U.S. Supreme Court to reverse the election results.

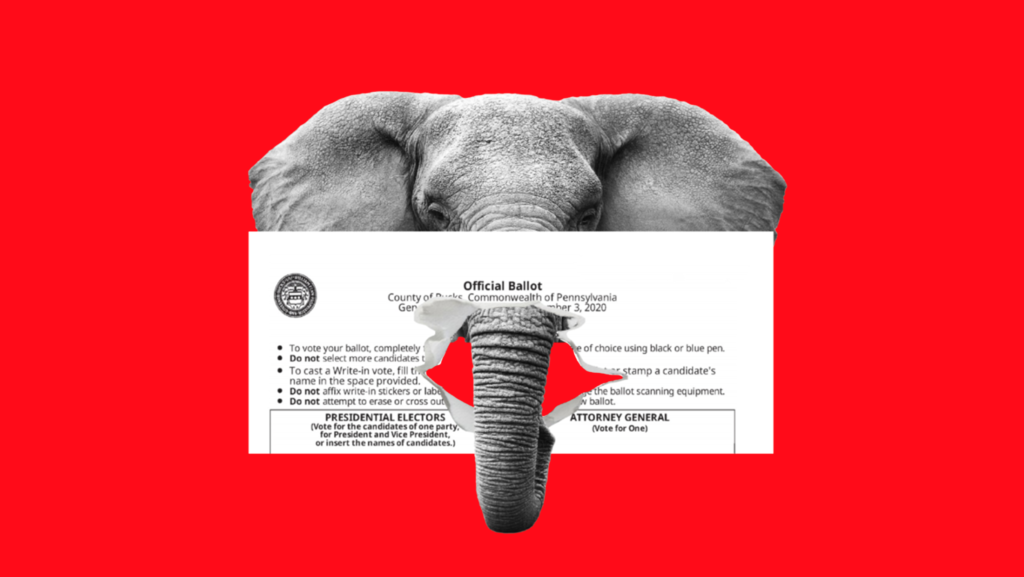

When Ken Paxton, the indicted attorney general of Texas who is facing a new federal investigation, brought this frivolous lawsuit in the Supreme Court to invalidate the 2020 elections in Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, people understood his likely motivation: to win a pardon by currying favor with Donald Trump.

In an odd way, I found solace in the fact that at least I could understand Paxton’s motivations: they were purely transactional.

But no similar bargain, however corrupt, could explain the behavior of the 17 other sycophantic state attorneys general who quickly followed Texas’s lead. It is as if they didn’t get the joke — Paxton wasn’t filing this lawsuit to win, he was filing it to get a pardon. While these other 17 attorneys general presumably didn’t need pardons, they blindly followed along, walking right past democratic norms, the expressed will of their voters and their own legacies and self-respect.

There is a Yiddish saying that a schlemiel is somebody who spills his soup and a schlimazel is the person it lands on. In this lawsuit, Paxton was the schlemiel. The other 17 AGs were definitely the schlimazel.

Even worse were the 126 Republican members of Congress who then added their names to this same effort. The 17 attorneys general could maybe claim that they were participating in this farce as their states’ chief lawyers. The 126 Republican members of Congress were, like court jesters, just there to bow and scrape in front of Dear Leader for his amusement.

If life were a movie, the Republicans’ humiliating display of self-loathing would end with a Republican politician boldly standing up to the president and showing political courage. But this is not a movie and Republican leaders failed us on the national stage.

However, we saw a few glimpses of the types of political courage Kennedy described from two other groups:

The first were judges. Most judges care enormously about their reputations for integrity. They are used to being called “Your Honor” and having people stand up when they enter and exit the room. Their desire to be perceived as independent guardians of the law was powerful motivation to stand up for democracy against the buffoonery that Rudy Giuliani, Sidney Powell and others displayed in their courtrooms.

The second group were the local election workers and officials who took pride in the work that they did and the elections they ran. They were not willing to disparage their efforts and their communities simply to please a defeated candidate. They had too much pride for that. They are the real heroes of this election.

Some will suggest that there were some high-profile Republican leaders who showed courage. While a few members of Congress, for example, recognized that Joe Biden was the president-elect when he was in fact the president-elect, that is not courage — that is merely accepting reality. And while their colleagues were trying to disenfranchise millions, they largely stayed silent. Their inaction will forever be etched in the national memory.

It would be wrong to say that this perverse lack of political courage is solely a symptom of Trumpism and that the Republican Party will somehow revert back to the Party of Lincoln at noon on Jan. 20. It won’t, and we would be naive to think so. We will continue to see an anti-democratic agenda leveraged through regressive policies, tactics and other craven acts.

Those of us who care about democracy can no longer afford to rely on the type of political courage Kennedy described in 1955. We must go further to display our own political courage by proposing and implementing new solutions to tackle these grave problems and not allow what Martin Luther King Jr. called “the appalling silence of the good people” to take hold without repercussions.

If, instead, we ignore the cowardice of these political leaders for another two or four years, we too will have failed to love both the public good and ourselves.