It’s Time To Reframe Voting Rights in the Courts

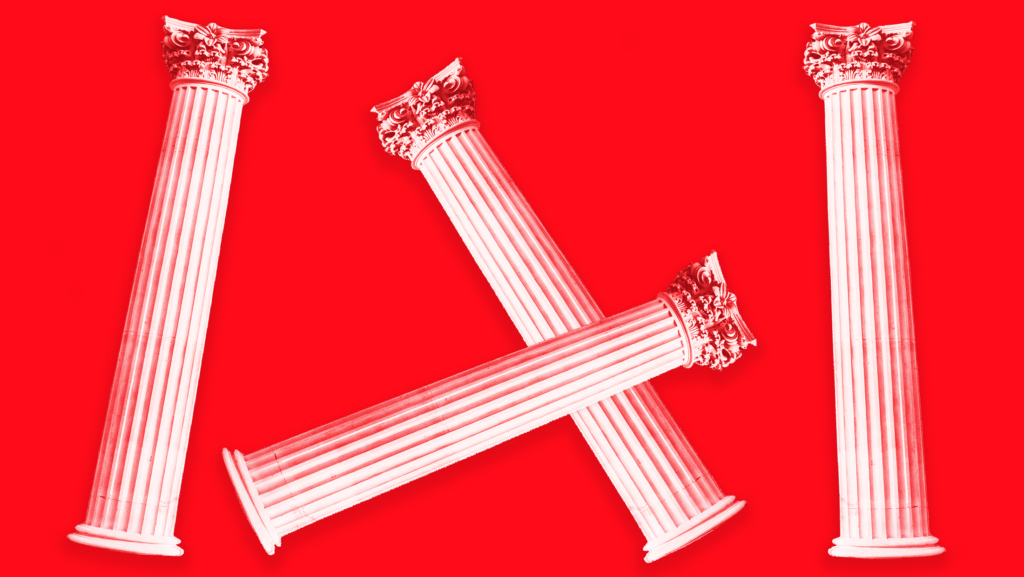

The right to vote is under attack. And unless we reform voting jurisprudence, courts are not equipped to stop it.

In 1964, a year before Congress passed the landmark Voting Rights Act, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Reynolds v. Sims that “since the right to exercise the franchise in a free and unimpaired manner is preservative of other basic civil and political rights, any alleged infringement of the right of citizens to vote must be carefully and meticulously scrutinized.”

Initially, the courts took this charge seriously. In a case about school board elections, the Supreme Court wrote “the deference usually given to the judgment of legislators does not extend to decisions concerning which resident citizens may participate in the election of legislators and other public officials.” In another case, the Court made clear that “before the right [to vote] can be restricted, the purpose of the restriction and the assertedly overriding interests served by it must meet close constitutional scrutiny.”

But while the Court has expanded its protection of other constitutional rights over time, it has done the opposite with the right to vote. This has been the product of years of conservative orthodoxy. It has also been aided and abetted by election officials who were happy to evade scrutiny of their decisions to restrict access to the franchise. For different reasons, conservatives and election officials sought to focus judicial attention on the difficulties in election administration rather than difficulties in voting. As a result, voting rights analysis became less voter centric in its orientation.

The key moment for those looking to undo the voter-centric approach came in 2007, when the Court upheld a strict new voter ID law in Indiana. Rather than closely scrutinizing the voting restriction, the Court balanced the burdens the ID law imposed on voters against Indiana’s purported state interests in enforcing the law. Since then, “a court evaluating a constitutional challenge to an election regulation weigh[s] the asserted injury to the right to vote against the precise interests put forward by the State as justifications for the burden imposed by its rule.”

The impact of this change in approach was evident in the reasons Indiana offered — and the Court accepted — to defend its new ID law. First, Indiana pointed out that in 2004 federal law had imposed a more limited, less sweeping ID requirement for first-time voters voting by mail. This, Indiana argued, supported the idea that ID laws were part of a modernization of elections.

Second, Indiana said that the new ID law would prevent fraud — while simultaneously admitting that there was no history or evidence of in-person election day fraud in Indiana elections.

Tucked into this portion of the opinion is this alternative rationale: “Moreover, the interest in orderly administration and accurate recordkeeping provides a sufficient justification for carefully identifying all voters participating in the election process.” In other words, the election administrators find it helpful.

Finally, Indiana claimed that the ID law would “safeguard voter confidence” in the election process. As the Court put it, “public confidence in the integrity of the electoral process has independent significance, because it encourages citizen participation in the democratic process.” Yet, a look at turnout rates before and after the ID law shows no evidence of this effect.

While Indiana’s reasons were given the benefit of the doubt, it was not so for the burdens asserted by affected voters.

The Court stated, without support, that “for most voters who need them, the inconvenience of making a trip to the DMV, gathering the required documents, and posing for a photograph surely does not qualify as a substantial burden on the right to vote, or even represent a significant increase over the usual burdens of voting.” The word “surely” is curiously carrying the burden of the sentence.

The Court did acknowledge that some voters would face a burden, particularly elderly and poor voters. But the Court explained that those voters can vote provisionally and “travel to the circuit court clerk’s office within 10 days to execute the required affidavit.” Left unanswered is how elderly and poor voters who cannot obtain the necessary papers are going to arrange travel to and from the circuit court, much less why their right to vote should be contingent on their ability to do so.

In the decades since, the balancing test imposed by the Court has been used to uphold even stricter ID laws, the shortening of early voting periods and restrictions on vote by mail. In 2020, it was used to uphold notary and witness requirements on absentee ballots during a pandemic when the most vulnerable Americans were directed to avoid contact with persons outside their home to avoid contracting or spreading a potentially fatal virus.

As a result of this balancing, the fundamental right to vote — which the Court has repeatedly recognized as “preservative of all rights” — has been relegated to just one of many competing considerations in conducting elections, and legislators, election officials and courts alike are empowered to encroach upon that right as long as they can identify a reason that the court concludes is good enough. Even more alarming, conservative courts have increasingly credited mythical or politically created concerns about non-existent voter fraud to justify making it harder for lawful Americans to exercise their “fundamental” right to vote.

The time has come to restore the more probing analysis of voting restrictions articulated 50 years ago.

This can and should be accomplished three ways:

1. Progressive judicial organizations need to prioritize the restoration of a more robust voting rights jurisprudence.

This includes overturning the balancing test approach to voting restrictions. Nominees to the federal courts should be probed on their views on the proper legal standard to apply to voting restrictions to ensure that we are appointing judges who legitimately respect and will protect voting rights.

2. Congress should enact a legislative fix that would require federal courts to employ the proper standard in protecting the right to vote.

Specifically, Congress should prohibit balancing the right to vote with the interests of the state. Congress should require courts to view restrictions on the right to vote skeptically and to apply strict scrutiny. This could be done as either a part of H.R. 1 — the For the People Act — or a stand-alone bill.

3. Progressive election administrators and advocacy groups must stop advancing ease of election administration as a rationale to limit voting rights.

Election officials too often view protecting voting rights as a burden. Election administration must bend to meet the needs of the voter, not the other way around. When there is a conflict between the needs of voters and the state, the tie must go to the voter, not the election official.

The hope expressed in Reynolds v. Sims that “history has seen a continuing expansion of the scope of the right of suffrage in this country” has not proved entirely correct. We must act now to turn the tide and fulfill this promise of democracy.