In South Carolina, Making Redistricting Work for All

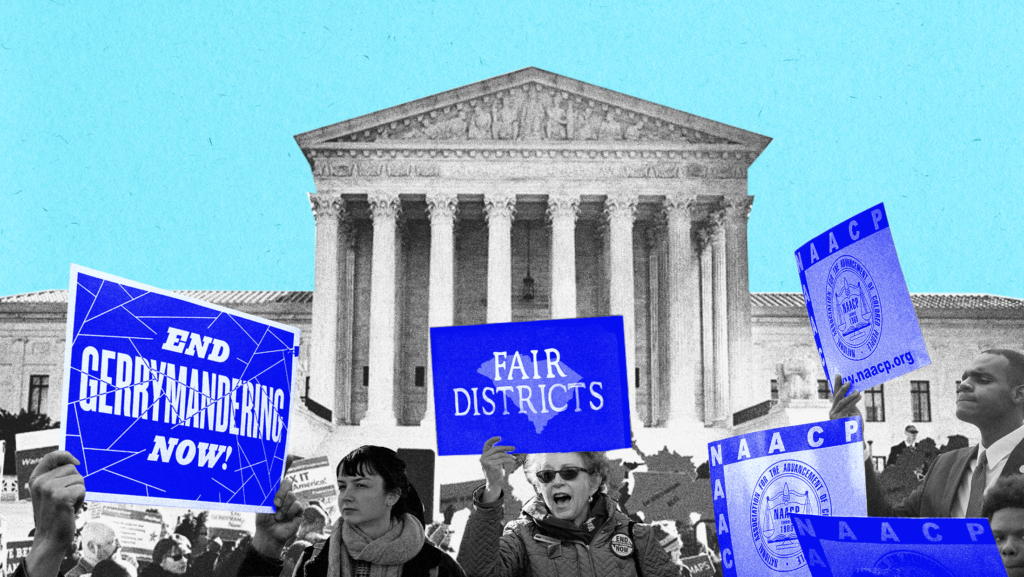

Today, the U.S. Supreme Court, our nation’s highest arbiter of law, will hear oral argument in a case that will shape the future of South Carolina’s Black communities by affirming whether South Carolina’s congressional map is a racial gerrymander — a practice by the state that has diluted their power in the political process.

As a South Carolina resident, the president of the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP and a plaintiff in this case, I have witnessed the undue burdens that unfair maps have placed on Black communities in my state. The outcome of this case will critically impact the degree to which Black communities are adequately represented, invested in, and sustained through congressional representation in the 1st Congressional District.

Redistricting lines ultimately determine the representation and allocation of resources at the state-level for at least 10 years. But these lines are more than just boundaries — they largely decide the fate of our communities. And for too long, Black communities in South Carolina have suffered grave consequences during this process.

Unfair district lines have meant unequal representation for Black communities that, for generations, has led to a lack of investment in health care, infrastructure, education, employment and sustainability. Over 40% of Black children in Charleston County are living below the poverty line, and graduate high school at much lower rates compared to white children. Black people in Charleston County earn less than two-thirds of what their white counterparts make, and the Black unemployment rate remains more than double the white unemployment rate. Black Charleston residents are disproportionately incarcerated, jailed and pulled over at traffic stops than white residents.

Black voters in the 1st Congressional District have already had to vote under an unconstitutional map once, during last year’s midterm elections, and should not have to continue to endure this indignity.

The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated and made us more keenly aware of these inadequacies. Due to insufficient schools and minimal resources, combined with no broadband internet in many areas, students attempted to learn virtually by sitting in school buses with hot spots. Economic challenges presented themselves as there were limited economic opportunities available in some areas for residents to work. A lack of access to medical care facilities meant insufficient treatment for COVID-19, and vaccines were not widely available. Black residents suffered a high mortality rate, making up 27% of the state’s population, but accounting for nearly half of hospitalizations and deaths.

During the most recent redistricting cycle, we asked for compliance, fairness and transparency. Instead, after a lengthy, prolonged legislative record by community leaders, activists and other community members to enact a map that complies with redistricting standards and does not harm Black voters, the South Carolina Legislature enacted a map that severely diluted the voting power of Black communities.

The map submitted by the redistricting coalition — which includes the South Carolina Conference of the NAACP as well as the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, ACLU, ACLU South Carolina and others — addressed traditional redistricting principles and other constitutional requirements and was informed by South Carolina’s voting patterns, history and relevant data. This care was necessary to develop maps that ensure Black voting power was not diluted, along with proposed maps that would have fairly allocated representation for all. Instead, in January 2022, the Legislature approved a map that severely diluted Black voting power.

In our federal lawsuit against the Legislature a month after the map’s enactment, we alleged that the congressional map constituted a racially gerrymander, and was enacted with discriminatory intent to diminish the power of Black voters. In January of this year, a three-judge panel unanimously ruled that the 1st Congressional District is a “stark racial gerrymander” — unfairly removing 62% of the Black voters, over 30,000 people, in Charleston County. The panel ordered the state to redraw a map prior to upcoming 2024 elections.

The time is now for Black voters to be fairly accounted for and fully heard. Black voters should be able to meaningfully participate in the political process. We need legislators that can speak to our communities’ challenges to represent us and when we speak about our concerns — they listen. Black voters in the 1st Congressional District have already had to vote under an unconstitutional map once, during last year’s midterm elections, and should not have to continue to endure this indignity.

At the heart of a multiracial democracy that thrives for all is the principle of fair representation — that every citizen’s vote is counted and that every voice is heard.

We are seeking a fair map that provides equal representation to all voters and that adheres to the standards of the U.S. Constitution. We are hopeful for the Court to affirm the three-judge panel’s earlier decision and for a new horizon in South Carolina’s history where communities receive the representation they truly deserve.

Brenda Murphy is the president of the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, a plaintiff in the U.S. Supreme Court case alleging that the state’s enacted congressional map is a racial gerrymander.