Headed Toward a Middle Ground? Today’s Argument in Moore v. Harper

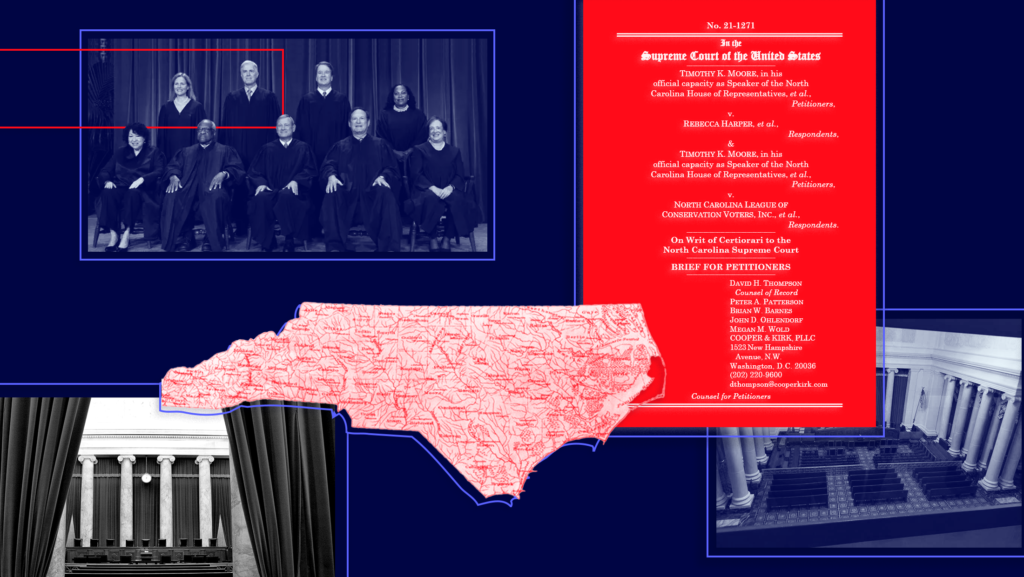

Every oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court is important. But even by those standards, the argument the Court heard today in Moore v. Harper was very important. This is because, while most cases hinge on an issue of either statutory or constitutional interpretation, it is rare that the Court entertains arguments on the creation of an entirely new legal theory or doctrine that involves both.

That theory, known as the independent state legislature (ISL) theory, suggests that because the Elections Clause in the U.S. Constitution gives state “legislatures” the ability to set the time, place and manner of congressional elections, the clause excludes state courts from applying state constitutions when reviewing federal election laws.

One of the big questions I had before this argument was how broadly the Moore lawyer would argue the case. And he went very broad, arguing from the start that “there can’t be a limit on the [state legislature’s] power” to regulate congressional elections “because it’s a federal function.” In practice, that would mean that state courts could not strike down state laws pertaining to federal elections for violating their state constitutions.

In retrospect, this decision by the Moore lawyer to take an absolutist position against state court review may well prove to be a mistake.

From the outset, Chief Justice John Roberts — himself a potential swing vote — questioned how the Moore lawyer’s position could be squared with the Court’s prior case law allowing state courts to review election laws. Roberts also pointed to the 1932 U.S. Supreme Court case, Smiley v. Holm, which held that governors may veto legislative enactments and was referenced many times throughout oral argument.

Significantly, Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett expressed similar skepticism. Even Justice Clarence Thomas, usually a stalwart conservative, asked tough questions of Moore’s lawyer. Indeed, one of the most striking takeaways from the argument was how little even the most conservative justices came to the Moore lawyer’s defense. Notably, while Justice Samuel Alito voiced support for the Moore parties’ position, even he expressed some reservations. In the three-hour argument, it was only Justice Neil Gorsuch who seemed entirely comfortable with the Moore lawyer’s argument.

Unsurprisingly, the three liberals — Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson — had little tolerance for what they clearly believed was an attack on state court review. During his time before the justices, the Moore lawyer was subject to withering questioning about how his argument fit with prior court precedent and practical experience.

Most importantly, as the argument wore on, there was an increased focus on the concurrence in Bush v. Gore. In that case, three justices wrote: “Though we generally defer to state courts on the interpretation of state law…there are of course areas in which the Constitution requires this Court to undertake an independent, if still deferential, analysis of state law.”

Several justices — most notably Roberts, Kavanaugh and Barrett — seemed to try to find consensus around a similar standard for state constitutional interpretation. Under such an approach, state courts could review state laws regulating federal election rules for compliance with state constitutions, but would need to adhere to the text of those constitutions in doing so.

In a sign of a potential consensus, by the end of the argument even Thomas and Alito were asking questions about how such a test would work. Whether or not they sign onto a middle of the road opinion, it clearly was where the center of the Court was today.

For voting rights advocates, the devil will be in the details of any opinion, but it feels like we dodged a bullet.

Aiding their efforts were the arguments by the lawyers for Harper. Both sets of lawyers — one for the state Harper parties and one for the non-state Harper parties — acknowledged that, in the most extreme circumstances, a federal court could find that a state court ignored the clear text of the state constitution. While a form of the ISL theory, such a holding would change relatively little in current jurisprudence and would lead the Court to uphold the North Carolina map in this instance.

Trying to predict the outcome of a case based on the oral argument is always dangerous. Justices ask questions for several reasons: to flesh out their own understanding of the facts, test the legal strength of the case and persuade the other justices. Yet, there are several themes that seemed to emerge today.

There was little appetite for the strongest form of the ISL theory offered by the Moore lawyer in this case. In an argument where all nine justices asked questions, only Gorsuch expressed unequivocal support for it. This seemed to surprise the Moore lawyer, who likely thought his argument would attract more reflexive support among the conservatives on the bench. Rather than pivot to where the Court was, he dug in with little effect. This ended up leaving him largely a spectator in his own case.

For their part, the lawyers supporting the North Carolina decision striking down the Legislature-drawn congressional map correctly read the room. Kavanaugh, Barrett and perhaps Roberts seemed inclined from the start to adopt a middle ground based on the concurrence in Bush. Though, in Bush, this language applied only to interpretation of state statutes, and as the arguments continued today there was significant discussion about how the same reasoning might apply to state court interpretation of state constitutions. Rather than fight the center of the court, the Harper lawyers defending the North Carolina decision tried to shape the contours of an eventual test for when a state court goes too far afield.

If the Court’s ultimate opinion follows the trajectory of the argument, I would expect future voting cases to face additional steps in the legal process but little more. State court election law decisions would be subject to an additional question: Did the opinion fairly reflect state law and the state constitution? While this would create new vehicles to attack pro-democracy court decisions, in practice it would more likely lead to longer, more carefully written state court decisions rather than change the outcome of many cases.

Today’s argument will likely assuage many, but not all, of the concerns raised by supporters of voting rights and fair redistricting. There seems little chance that the Court will deny state courts their traditional role of interpreting and applying their state constitutions to state laws governing elections. For voting rights advocates, the devil will be in the details of any opinion, but it feels like we dodged a bullet.

Proponents of the ISL theory will likely be disappointed by today’s argument. The Court greeted the arguments from the Moore lawyer coldly from the start and the Court seemed to coalesce around a middle ground approach petitioners rejected at the beginning of the day. I suspect some will privately second guess the litigation strategy here and the decision to make this case the vehicle to argue a broad ISL theory.

No matter what the outcome is, we should expect this case to be among the most important and last cases decided by the Court. As a result, I would not expect a decision before late June.