What Trial Testimony Tells Us About South Carolina Racial Gerrymandering

Every year, upwards of 8,000 petitions appear before the U.S. Supreme Court but, unlike other appeals courts, it is not required to hear most cases. In its 2022-23 term, the Supreme Court agreed to hear just 60 cases. As the Court has begun to indicate which cases it will schedule for the next term, among the short but growing list is a redistricting case out of South Carolina.

After the state redrew its districts with 2020 census data, the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP challenged the congressional map for violating the 14th and 15th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. Specifically, the plaintiffs claim that the map was a racial gerrymander, a claim rooted in the 14th Amendment that means race was the predominant factor in deciding where to place voters in districts without a compelling reason to do so.

Importantly, the 14th Amendment racial gerrymandering claims invoked in this case are distinct from claims involving Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. That means that this case is not directly implicated by the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent Section 2 decision in Allen v. Milligan.

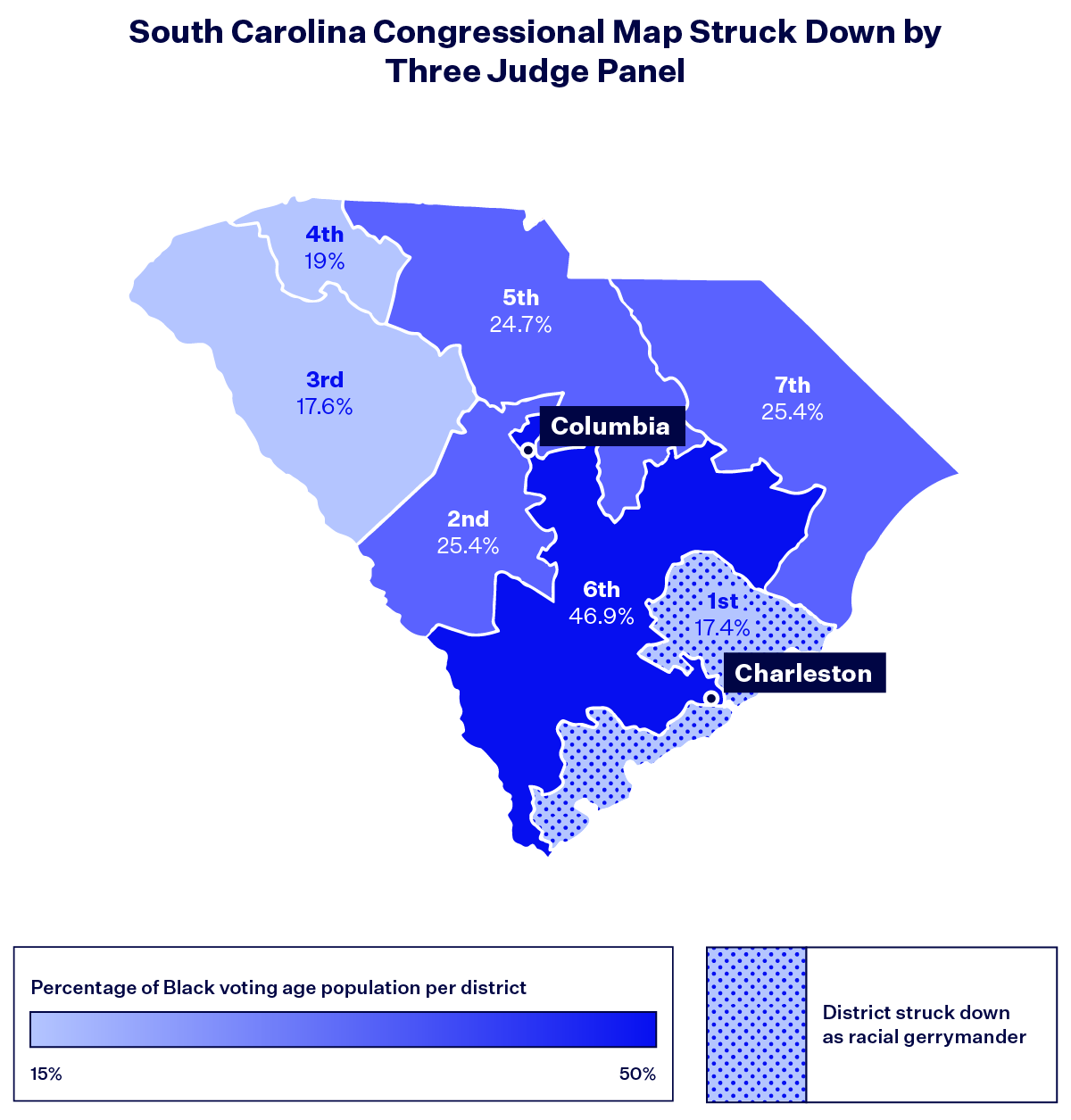

In January 2023, a three-judge panel struck down the new congressional map, finding that one of the districts was likely racially gerrymandered. The panel found that the “movement of over 30,000 African Americans in a single county from Congressional District No. 1 to Congressional District No. 6 created a stark racial gerrymander of Charleston County.”

In turn, the Republican state lawmakers defending the map appealed the decision directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. Under federal law, the Supreme Court was required to affirm or reverse the three-judge panel’s decision. However, on Monday, May 15, the Court announced that it would hear the case next term, with full briefing and oral argument to be scheduled for fall 2023.

Before the Supreme Court zones in on this case, we’re rewinding back to a multi-day trial in October 2022 where both sides presented experts, evidence and witnesses before the three-judge panel. In trial transcripts for the plaintiff’s witnesses, the testimony reveals the intentional weakening of Black communities’ voting strength, an opaque redistricting process and a general culture of unresponsiveness among South Carolina congressional’s delegation.

Experts for the plaintiffs utilized data to exemplify the extent of South Carolina’s gerrymandering.

The plaintiffs, including the South Carolina NAACP, focused on proving that three of South Carolina’s districts — the 1st, 2nd and 5th Congressional Districts — were racial gerrymanders. As a reminder, after the trial, the three-judge panel only struck down the 1st Congressional District.

The 1st District, currently represented by U.S. Rep. Nancy Mace (R-S.C.), was less competitive for Democrats after the recent redraw compared to the map enacted in 2012, despite growth in the nonwhite population that might suggest otherwise.

The plaintiffs argued that communities with predominantly Black populations “were all cracked—preventing Black voters from electing candidates of choice (or otherwise influencing elections), while communities with predominantly white populations…were kept or selectively made whole to fortify white voting power in six districts.”

In the early 1990s, the 6th Congressional District was created as a Black-majority district with U.S. Rep. Jim Clyburn (D-S.C.) elected to represent it ever since. The 6th Congressional District remains the only district in the map enacted in 2022 that gives Black voters the opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice.

For the first time since the creation of this Black-majority district, the Legislature adopted a map where the Black voting age population in the 6th Congressional District dropped under 50%. That decrease suggested to many that other districts might provide Black voters better electoral opportunities; the enacted map did not do so.

During the trial, expert witness and mathematician Moon Duchin argued that “between the reduction of Black voting age population in CD 6…[a]nd the increased concentration of Black voters in relevant areas, there’s more opportunity than ever to have Black voting power reflected in other districts.”

However, that potential was not reflected in the map. Duchin also spoke to the intentionality of selecting a map that spreads Black voters across the districts in the way it does. In fact, alternative maps Duchin generated show that “tens of thousands of automatically generated plans all easily provide more [electoral] opportunity. There were not one, not two, but just a vast number of ways to be less dilutive.”

One of those alternative maps was created by Robert Oppermann, a lawyer and demographer hired by a South Carolina lawmaker to construct maps different from those proposed by Republicans. In regards to an early draft plan (that was very similar to the enacted map), Oppermann noted: “There are a number of county splits here that are above and beyond what would be necessary to comply with the law and certainly comply with one person, one vote. The shape of some of the districts is strange.”

Most importantly, in a proposed map with 10 county splits, Oppermann noted that eight of the 10 county splits occurred along the boundary of Congressional District 6. “And that suggested to me a certain kind of intent,” he concluded, referencing the 6th Congressional District as the region with the highest percentage of Black voters.

Advocates and lawmakers alike focused on the broken and rushed process to pass maps.

A crucial aspect of the NAACP’s case focused on intentional racial discrimination, noting that “the Legislature went forward with the proposed plans even though, during the legislative process, Black legislators and members of the public repeatedly warned that they would harm Black South Carolinian voters. Alternative proposals existed which would satisfy the Legislature’s criteria and not dilute Black voting strength.”

Several current South Carolina lawmakers took the stand in the trial to speak about the legislative process: one that was apparently nonresponsive to public feedback.

South Carolina Rep. John King (D), a member of the state House Judiciary Committee’s subcommittee on Election Laws, was excluded from the ad hoc committee given redistricting authority. “[I]n my opinion, had I been chair, [I] would have given every member around that table an opportunity. We would not have rushed and voted that particular piece of legislation probably out that day,” King explained on the stand. “I would have given it due diligence of a full investigation of the maps that will affect us for the next 10 years.”

Another state lawmaker, Sen. Margie Bright Matthews (D), reiterated the rushed nature of the votes on the maps, testifying that she had to halt the proceedings to make sure that she and other Democratic senators could even get a copy of the map proposals.

On the advocate side, Lynn Teague, who works with the League of Women Voters of South Carolina, lamented the insufficient time for public feedback. “The League was set up to do this. We had made this a priority for several years,” she explained how her group was prepared to give feedback in a limited period. “But for the average member of the public, the time frame was very short.”

Teague continued to highlight the consistent themes in the public’s testimony: “We heard over and over again that people were disturbed about how fragmented they felt their community was. This was true in Richland, it was true in Charleston, and it was also true in other areas.”

“I feel as though…they did not take into consideration what was said at the public hearing,” a resident of the 6th Congressional District testified, “and instead, continued the practice of reducing the capacity of Black voting communities.”

“[The map] doesn’t open up an avenue for us to elect someone who will speak up:” Voters expressed the importance of responsive policymakers.

Apathy from elected officials is a side effect experienced by communities who lack the voting power to influence electoral outcomes. Throughout the testimony of several witnesses, this thread was explored: A 70-year old resident of St. Stephen, South Carolina — a small town in the 1st Congressional District — spoke about the work he’s doing to ensure that rural residents get broadband access and clean water.

However, he was asked whether Mace, who was running for reelection at the time, had campaigned in his community at all. She had not.

A resident of the 5th Congressional District was concerned that her hometown, the city of Sumter and Sumter County, were split by the map. The resident explained that she did not feel like her representative, U.S. Rep. Ralph Norman (R-S.C.) paid attention to her community. “I have yet to see Representative Norman in my area…As hot as the campaign season is right now, there is not one campaign sign of Representative Norman. However, there are signs in the subdivisions of Sumter [that are majority-white].”

To illustrate the culture of unresponsiveness, King, who represents an area that falls within the 5th Congressional District, gave an anecdote of when he spoke with his U.S. House representative at the time, former U.S. Rep. Gary Simrill (R-S.C.). Instead of working with the state lawmaker to support his constituents, Simrall “made it very clear” that he could not help out, instead asking King to contact Clyburn. “And Congressman Clyburn is not our representative, but I did contact Congressman Clyburn’s office.”

In light of the feeling that they were ignored by lawmakers, witnesses spoke about the host of issues that mattered most to their communities: broadband access, health care in rural communities, education, environmental population, affordable housing and more.

“[H]aving an individual that is connected to those issues and understands the importance to everyday voters would allow them to also champion legislation that could help alleviate” the challenges plaguing their community, a South Carolina voter emphasized.

Taiwan Scott, a plaintiff in the case who lives on Hilton Head Island in the 1st Congressional District, echoed a similar sentiment: “I believe, again, that [the map] doesn’t open up an avenue for us to elect someone who will speak up and advocate for historical concerns that continue to arise and just continue to escalate.”