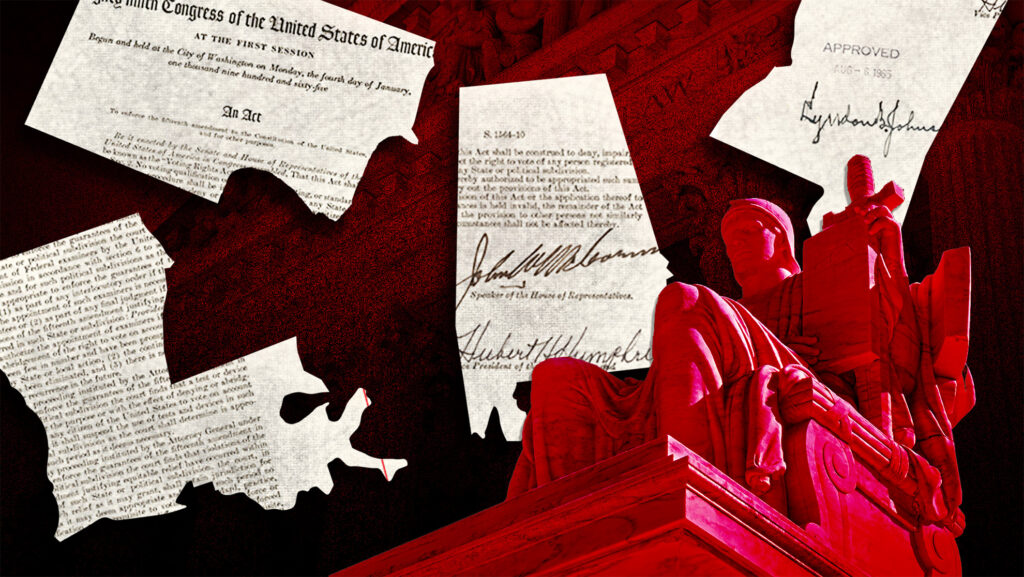

The GOP Is Attacking the VRA From All Angles — and Could Soon Make it All But Useless

It took nearly a century for Congress to enact legislation to enforce the 15th Amendment.

It may take conservatives on the U.S. Supreme Court only a little more than a decade to fully eviscerate that law — the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA).

After a 2013 ruling neutered the strongest plank of the VRA, it now faces an unprecedented and multi-pronged legal attack that could leave the landmark civil rights law all but useless for stopping racial discrimination in voting.

A raft of lawsuits aimed at narrowing the VRA, or gutting its most powerful remaining section completely, are either now before the court or waiting in the wings.

In cases arising out of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and North Dakota, Republicans have sought to make it much harder to use the VRA to challenge discriminatory voting practices like racially gerrymandered electoral maps. The Supreme Court will hear reargument in one of those — Louisiana v. Callais.

The unfolding assault on voting rights — unprecedented federal legislation to radically tighten voting rules also has passed one house of Congress — makes clear that, despite Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. ‘s oft-repeated assurance that the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice, there’s nothing preordained about the struggle for access to the ballot.

“Every advancement in democratic rights — every extension, every improvement — is met sooner or later by a counter reaction, because there are some forces or folks that do not want to tolerate real democracy, who feel like their interests are threatened if there really is democracy,” said Alexander Keyssar, a professor at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. “In the long run, the story is not a story of continuous improvement or continuous democratization. It’s more a story of two steps forward and one step back — and sometimes it’s two steps forward and two steps back”

“We’re now seeing one of a variety of periods of rolling back on democracy, of resistance to democracy,” Keyssar added.

Right-Wing Lawyers Race to Supreme Court

In the decades after the VRA’s enactment, courts tinkered with the law’s applicability and scope at the margins, but largely rebuffed attacks aimed at disabling the statute altogether. Then, in 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder ruling, the Supreme Court struck down the law’s requirement for certain jurisdictions, mostly in the South, to get all voting changes approved, or “pre-cleared,” by the federal government, because of histories of racial discrimination in those places.

Since then, the court has grown more conservative, leading VRA opponents to launch an all-out assault on the law’s most powerful remaining provision, Section 2, which bans racial discrimination in voting. They have fired off even flimsy theories on the off chance one might stick.

“These are all maneuvers you only undertake if you think the Supreme Court is deeply sympathetic to your side,” said Nicholas Stephanopoulos, a Harvard Law School professor and prominent election law expert. “You’ve got movement conservative lawyers thinking they have kindred spirits on the Supreme Court, [so they are] looking at all of these implausible, weak arguments to undermine Section 2, but kind of knowing that even weak arguments have a decent chance of being accepted by this court.”

The courts have long held that Section 2 of the VRA allows plaintiffs — including individual voters — to challenge voting laws that have discriminatory effects, as long as certain other factors are in place suggesting race played a role. It’s been used most frequently to block electoral maps that dilute the voting strength of minority groups and force the drawing of more districts where racial minorities can elect the representatives of their choice.

“The big picture is that plaintiffs have been recently filing and winning some — not a huge number, but some — Section 2 cases,” said Stephanopoulos. “So this has caused some conservative opponents of the VRA just to get very agitated and to look for all kinds of strategies and legal arguments that they can use to limit Section 2.”

In fact, though, Section 2 has been in conservatives’ crosshairs for decades. As a young lawyer at the U.S. Justice Department, John Roberts — now Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, and the author of the Shelby County opinion — famously wrote a 1982 memo opposing crucial efforts to strengthen Section 2, which ultimately were passed by Congress and signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

In addition to the offensive against the VRA, Republicans are also currently leading attacks on laws protecting overseas voters (including active military), disabled voters, and mail-in voters.

Experts caution that no one really knows what the court might do in Callais or any of the other cases challenging the VRA that could end up before it. “The short version is that it’s way too early to know what to expect out of all of this when it shakes out,” Justin Levitt, a professor at LMU Loyola Law School and a former Justice Department official during the Obama administration, wrote in an email.

The last time voting-rights advocates were this worried about the fate of the VRA was two years ago, when the court considered another broad challenge to Section 2 in Allen v. Milligan. In a 5-4 decision, the court ultimately upheld Section 2, but in his concurrence, Justice Brett Kavanaugh suggested he might be open to a “temporal argument,” like the one used by plaintiffs in Shelby County. That claim was that racism in the South was no longer so serious a problem that it required what Roberts called the “strong medicine” of pre-clearance.

After Louisiana drew new congressional maps following reapportionment in 2022, the state was successfully sued by voters and civil rights groups under Section 2, leading the courts to order the state in 2024 to draw new maps with an additional district in which Black voters were a majority. Soon after, the plaintiffs in Callais, twelve “non-African-American” voters, sued to block the new map, arguing that the VRA’s remedy for the old map’s vote dilution — creating a second majority-minority district — was overly focused on race, thereby violating the 14th Amendment.

The district court agreed that the new maps were unconstitutional, leading to appeals to the Supreme Court, which heard arguments on whether the district court erred in the spring.

But when the court delayed issuing an opinion in Callais this summer, and then announced a rehearing in October on “[w]hether the State’s intentional creation of a second majority-minority congressional district violates the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments to the U. S. Constitution,” it led many observers to predict the court might be readying to make a sweeping ruling that could decimate the VRA.

“It’s really ominous,” Stephanopoulos said. “This is Kavanaugh’s pet issue. He’s now teed it up. And, so, is he going to flinch from addressing it? I don’t know.”

Section Two Faces Assault on Two Fronts

After the Supreme Court’s rehearing order, Louisiana reversed its legal arguments. Before, it had argued its congressional map was drawn with political considerations, not racial ones, at the forefront. Now, it essentially joined the conservative plaintiffs in outright attacking Section 2’s remedy – creating a second majority-Black congressional district — as unconstitutional.

Despite the court’s unmistakable delay in issuing a ruling in Callais, this process for questioning the VRA’s viability is actually incredibly rushed, Stephanopoulos said.

“It’s so slapdash for the Supreme Court now to be considering whether to strike down Section 2 when this issue has not been litigated at all in this case,” Stephanopoulos said. “This case was a racial gerrymandering case. It’s not a case about Section 2…. It’s totally avoiding the need for a proper record and proper fact finding.”

Other Republican-led states have taken notice and filed for stays in their redistricting lawsuits. Alabama essentially asked the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals to stay a lower court’s decision ordering new congressional maps, until Callais is decided.

If the Supreme Court’s majority does decide that the VRA’s standard remedy for unconstitutional vote dilution — more majority-minority districts — is, in fact, unconstitutional, it would be difficult for Congress to “fix” the VRA, even if you ignore the political obstacles. Pro-voting lawmakers would need to consider “very novel” ideas, Stephanopoulos said, like replacing the current system of single-member districts with multi-member proportional representation.

And those political hurdles would likely be taller than they are today. The VRA is one of the few tools left to block extreme partisan gerrymanders, which also frequently create racial gerrymanders. If the court axed Section 2, Republicans in the south could potentially step up their mid-decade redistricting push into southern states, leading to eight more safe GOP seats, as the New York Times’ Nate Cohn recently noted.

The Potential Privation of Section 2

The GOP’s other primary line of attack on Section 2 is that only the Attorney General, not private plaintiffs like voters or voting-rights advocates, can sue to enforce the law. Section 2, goes the claim, contains no “private right of action.”

Last year, the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with that argument in an Arkansas case, effectively gutting Section 2 in Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota.

While the plaintiffs in that case decided against appealing to the Supreme Court, fearing it would entrench the decision across the entire nation, another group is pressing ahead this year.

Native Americans led by Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians had successfully challenged North Dakota’s state legislative maps both under the VRA’s Section 2 and Section 1983 — the provision of the U.S. Code that allows citizens to sue the government when their civil rights are deprived. They won, leading to a VRA-compliant map being used in 2024. But North Dakota appealed to the 8th Circuit, which echoed its decision last year and held that private plaintiffs can’t bring Section 2 claims via Section 1983. In response, the tribes are appealing to the Supreme Court, which agreed to pause the 8th Circuit’s ruling in North Dakota while it deliberates.

As that has been happening, Mississippi also asked the Supreme Court to rule on a private right of action, appealing a 5th Circuit Court of Appeals decision. And Alabama is still fighting Milligan v. Allen, recently asking the Supreme Court to consider new arguments to reverse the 5th Circuit determination that there is a private right of action, while also raising the constitutional questions at stake in Callais.

Since 1982, more than 400 Section 2 cases have been litigated in federal court, leading to 182 successful challenges, according to data compiled by University of Michigan researchers. Of those, only 15 were brought by the Attorney General alone. “If private plaintiffs can’t sue, that basically makes Section 2 a dead letter,” Stephanopoulos said.

That’s especially true under the current administration. Under Attorney General Pam Bondi, the Department of Justice has reversed its position on numerous voting rights cases, including Callais.

Similarly, the 8th Circuit also ruled this summer that the VRA’s Section 208, which ensures that voters who have disabilities or limited English proficiency can get help casting their ballots, also does not explicitly provide a private right of action. That decision upheld an Arkansas law that makes it a crime for someone other than a poll worker to assist more than six people cast their ballots. A day later, the RNC urged the 5th Circuit to adopt the same interpretation.

The VRA made the fight for democratic rights a federal issue, Keyssar noted. Even if the courts don’t gut Section 2 completely, preventing private actors from suing would leave the law’s enforcement in the hands of lawyers who appear more worried about claims of “DEI racism,” than voting dilution.

“The federal government itself is retreating to a hands off stance towards voting rights and the law of democracy,” Keyssar said.