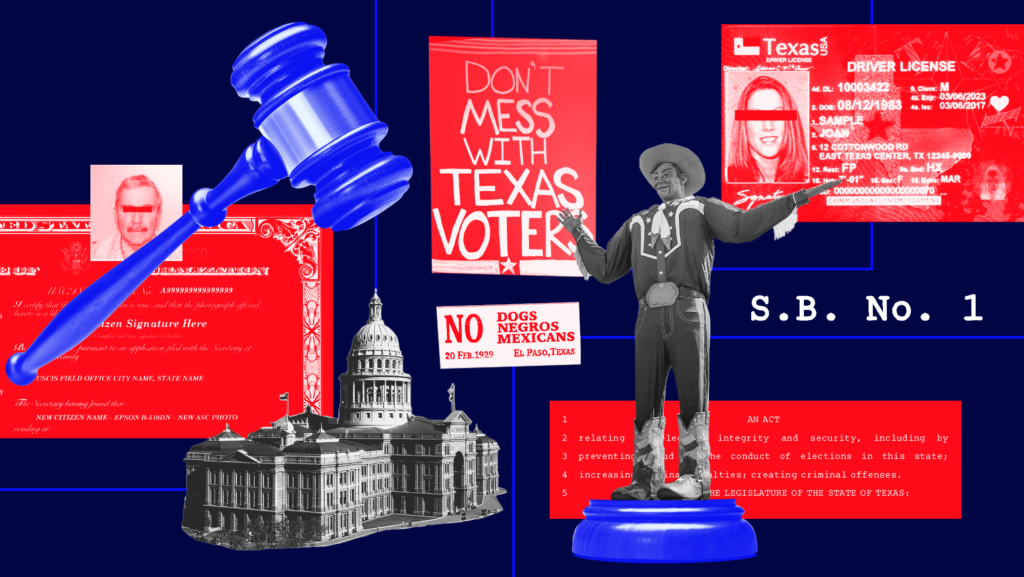

Texas Omnibus Voter Suppression Law S.B. 1 Will Be Put to the Test at Federal Trial

“Today, more than 50 Democratic members of the Texas House left Austin…not because we want to — it breaks our heart that we have to do it — but we do it because we are in a fight to save our democracy. The nationwide Republican voter suppression efforts are coming to a crisis point in the state of Texas right now.”

These remarks came from the former Chair of the Texas House Democratic Caucus, Chris Turner (D-Grand Prairie), who joined his colleagues in a July 2021 exodus to Washington D.C. that was motivated by Senate Bill 1 — state Republicans’ omnibus voter suppression package. Turner and his fellow lawmakers fled to the nation’s capital during a special legislative session with a specific goal: stymie the legislation by breaking quorum — the minimum number of legislators needed to hold a vote — and prevent S.B. 1’s sweeping anti-voting measures from becoming law.

Indeed, this was not the first time Democratic legislators deployed drastic measures in opposition to S.B. 1’s voting restrictions that disproportionately target minority voters and voters with disabilities. At the conclusion of the state’s regular legislative session back in May 2021, House Democrats prevailed in blocking the enactment of a previous iteration of the legislation after staging a coordinated walk-out that denied Republicans the quorum needed to conduct business.

After overcoming Democratic resistance, S.B. 1 became law in September 2021. Starting today, the law finally heads to trial.

Despite Texas Democrats’ valiant efforts, which garnered national attention and engendered calls for renewed federal voting rights legislation, Texas Gov. Greg Abbot (R) signed S.B. 1 into law on Sept. 7, 2021 following a second special legislative session. Enacted under the guise of “election integrity” and “preventing fraud” in the wake of the 2020 election — where no evidence of widespread voter fraud occurred — the Republican-sponsored law doubles down on voting restrictions in the Lone Star State. Even prior to the passage of S.B. 1, Texas already ranked last in the nation with regards to voter registration and voting access.

Leading up to and directly following the enactment of S.B. 1, several voting and civil rights groups along with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) swiftly filed federal lawsuits challenging the law’s numerous anti-voting provisions. A combined total of six active federal lawsuits challenge S.B. 1, all of which are consolidated under one case, La Unión del Pueblo Entero v. Abbott. Together, these lawsuits bring claims against S.B. 1 under various federal voting and civil rights statutes as well as portions of the U.S. Constitution that safeguard voters from discriminatory voting practices.

Today — nearly two years after the enactment of S.B. 1 — a six-week bench trial begins in the consolidated legal challenge to the infamous election law. Below is a breakdown of S.B. 1’s most salient anti-voting provisions as well as the legal claims against them, many of which will be argued at trial before a federal district court in San Antonio, Texas.

S.B. 1 wages a multi-pronged attack on mail-in voting.

The law imposes strict ID requirements for mail-in voting.

One of the ways in which S.B.1 restricts mail-in voting is via ID requirements that increase the likelihood of arbitrary disenfranchisement. Under the law, voters must provide a voter identification number — either their driver’s license number or the last four digits of their Social Security number — on both their mail-in ballot application and their completed ballot.

Multiple sets of plaintiffs in the consolidated lawsuit will raise challenges to these identification requirements at trial, alleging that they interfere with the right to vote and were enacted with a discriminatory purpose “following record-setting voter turnout among Texas’s Black and Hispanic populations.” In particular, the plaintiffs assert that these requirements violate multiple federal voting and civil rights laws, including Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA), which prohibits denying the right to vote on the basis of race. They also maintain that these aspects of S.B. 1 run afoul of the 14th and 15th Amendments’ prohibition on intentional racial discrimination.

S.B. 1 previously required clerks to reject mail-in ballot applications and completed mail-in ballots if they did not include a voter identification number that matched the one provided on an individual’s original voter registration application. As of Aug. 17, 2023, S.B. 1’s identification number matching requirements are preliminarily blocked due to a ruling by Judge Xavier Rodriguez of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, who granted a request by the DOJ and OCA-Greater Houston to strike them down.

Rodriguez — a Bush appointee who is presiding over the case — agreed with the plaintiffs’ argument that these provisions violate the Materiality Provision of the Civil Rights Act, which protects voters from disenfranchisement on the basis of trivial errors that are unrelated to voter eligibility.

Although the stringent identification matching requirements are now blocked, staggering rates of mail-in ballot rejections demonstrate how the S.B. 1’s pernicious anti-voting provisions have yielded tangible and far-reaching consequences for Texas voters. According to reporting from the Associated Press, the now-struck down provisions of S.B. 1 contributed to the rejection of nearly 23,000 mail-in ballots — 13% of all mail-in ballots cast — in Texas’ 2022 primary election. Mail-in ballots cast by voters of color were rejected at disproportionately high rates and a significant portion of rejected mail-in ballots were cast in Houston, home to the heavily Democratic and diverse Harris County.

The law restricts other aspects of mail-in voting such as drop boxes, distribution of mail-in ballot applications and more.

In addition to hindering mail-in voting through identification requirements, S.B. 1 effectively bans the use of ballot drop boxes in the state, as it requires voters to return their early voting ballots directly to elections officials. Various plaintiff groups bring claims against this provision under the VRA and U.S. Constitution that will be litigated at trial.

Another provision of the law aimed at mail-in voting goes so far as to impose criminal penalties — a state jail felony of up to 10 years — on local election officials who proactively send mail-in ballot applications to prospective voters who did not request them (even if the voter were already qualified to vote absentee). S.B. 1 also applies these penalties to local election officials who authorize the use of tax dollars for third parties to send out unsolicited mail-in ballot applications. In turn, these provisions aim to prevent counties from facilitating get-out-the-vote efforts that are often led by third-party voter registration organizations.

The pro-voting groups behind the consolidated lawsuit challenge these criminal provisions under the U.S. Constitution, VRA and other statutes, contending among other claims, that they place an undue burden on the right to vote and were “enacted with an impermissible discriminatory intent against Black and Latino voters.”

S.B. 1 limits other fundamental aspects of the voting process.

The law bans drive-thru voting and cuts down early voting hours.

At the heart of S.B. 1 are provisions that target innovations pursued by Harris County, the state’s most populous and diverse county, during the 2020 election. In response to the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, county officials instituted 24-hour early voting as well as drive-thru voting, which allowed voters to cast a ballot from inside their motor vehicle. S.B. 1 rolls back this progress by limiting drive-thru voting to individuals with a disability that prevents them from physically entering a polling location, while simultaneously restricting most early voting to the hours between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m on non-holiday weekdays.

According to written expert witness testimony, “the elimination of drive-thru voting attacks a procedure used disproportionately by minority voters in Harris County,” with voters of color taking advantage of this voting option at significantly higher rates than their white counterparts. Consequently, the plaintiffs maintain that these portions of S.B. 1 were enacted with unconstitutional racially discriminatory intent. The lawsuit also contends that these restrictions have a disparate impact on minority voters in violation of Section 2 of the VRA.

The law empowers and loosens regulations on partisan poll watchers.

S.B. 1 bolsters the autonomy of partisan poll watchers — who monitor polling place activity on behalf of political parties — by affording them greater access to polling places and vote-tabulating centers. The law states that partisan poll watchers “may not be denied free movement” within a polling place and even makes it a criminal offense for an election official to obstruct the view of a poll watcher. In this way, the law prioritizes private poll watchers at the expense of election officials, who face unprecedented levels of harassment and violence in the wake of the 2020 election and Republicans’ promulgation of the “Big Lie.”

As explained by Professor Franita Tolson of the USC Gould School of Law, the provisions of S.B. 1 that empower partisan poll watchers have a disproportionately adverse impact on minority voters, who have historically been intimidated and deterred from voting as a result of poll watcher tactics dating back to the Jim Crow era. “The conception of poll watchers as innocent overseers, tasked with ensuring a fair election, cannot be divorced from their historic role of policing the boundaries of the white electorate to keep minorities out,” Tolson wrote in an expert report submitted on behalf of the plaintiffs.

Like the many other provisions challenged in the lawsuit, the plaintiffs assert that those emboldening poll watchers have the intent and effect of discriminating against Black and Latino voters and place an undue burden on the right to vote.

The law creates onerous barriers for voters who need assistance.

S.B. 1 overtly targets the state’s most vulnerable voters, including those with disabilities and limited English proficiency, by erecting unnecessary barriers to voter assistance. The law specifically establishes that individuals who assist voters must fill out forms indicating their relationship to the voter whom they are assisting. It also requires assistors to swear under a new oath that they did not “pressure or coerce” the voter to choose them as an assistor. Finally, the law subjects certain assistors — those who did not previously know a voter — to possible criminal penalties if they “solicit, receive, or accept compensation” for helping a voter.

According to Professor Douglas Kruse of Rutgers University, these provisions of S.B. 1 “create an extra burden in voting for a significant number of people with disabilities across the state of Texas and may prevent some from voting altogether.”

At trial, many of the plaintiff organizations challenge S.B. 1’s host of restrictions on voter assistance under Section 208 of the VRA, since they impede the rights of voters with disabilities and limited English proficiency to receive assistance from a person of their choosing. Some groups also argue that these provisions contravene other federal statutes — such as the Americans With Disabilities Act — as well as the U.S. Constitution.

The law establishes new opportunities for voter purges.

S.B. 1 increases opportunities for voter roll purges by requiring the Texas secretary of state to perform monthly reviews of citizenship data from the Texas Department of Public Safety in order to cancel voter registrations of suspected noncitizens. Reporting by the Texas Tribune indicates that this error-prone process has led to individuals who are naturalized citizens being erroneously labeled as noncitizens and perpetuates the state’s sordid history of racially-motivated voter purges. S.B.1 also mandates that the secretary of state shall conduct quarterly “residency checks” using a statewide voter registration list to ensure that voters reside in the counties where they are registered.

One of the plaintiff organizations, Mi Familia Vota, claims that S.B. 1’s voter roll maintenance provisions violate Section 2 of the VRA and the 14th and 15th Amendments since they intentionally discriminate against minority populations.

With the commencement of a federal trial, S.B. 1 finally has its long-awaited day in court.

Over the next month and a half, the court will weigh evidence and hear testimony from both the pro-voting groups who brought the consolidated lawsuit and the Texas state officials defending S.B. 1. Ultimately, it is up to a federal judge to decide which portions of S.B. 1 will withstand judicial review and remain on the books.

Whatever the outcome of the trial, it is abundantly clear that S.B. 1’s anti-voting provisions are among the most suppressive in the country and serve to disenfranchise Texas voters — especially voters of color — who bear the brunt of the law’s negative effects.