How Lies Have Turned Into Threats Against Election Workers

“There is nowhere I feel safe. Nowhere. Do you know how it feels to have the president of the United States target you?”

The words of Ruby Freeman, a Georgia election worker whose life was upended by the “Big Lie,” reverberated through the U.S. House committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack. Freeman and her daughter Shaye Moss were election workers in Georgia during the 2020 election. Former President Donald Trump and his lawyer Rudy Giuliani targeted the two Black women; they received death threats and vile, racist harassment, including an attempted “citizen arrest” by a mob of strangers.

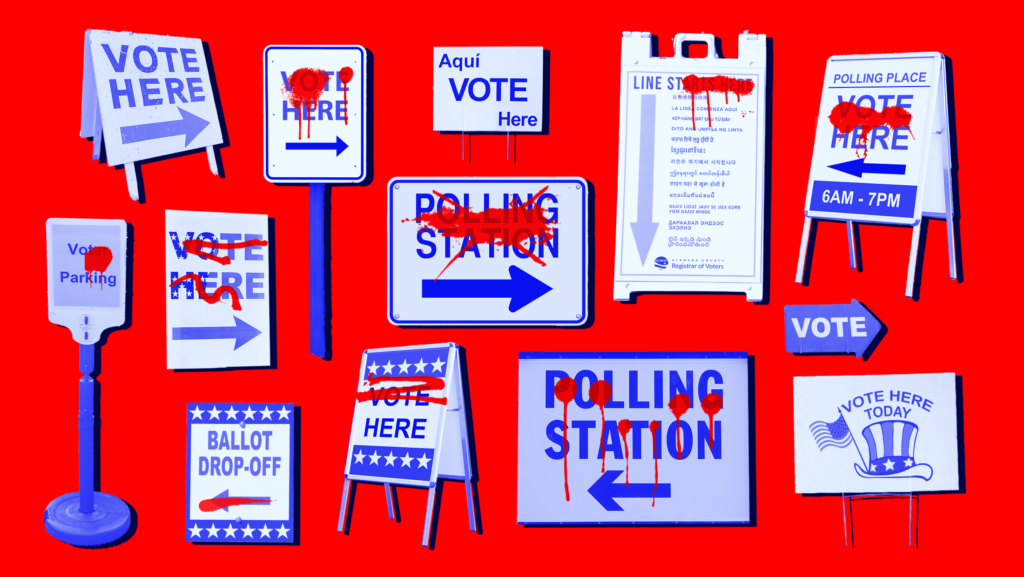

Threats to election workers are on the rise nationwide.

It’s not just Freeman and Moss: There’s an abundance of similar stories from election workers across the country. The structure, size and responsibilities of election offices depends on the state, or even the county. These officials are responsible for supervising voter registration and mail-in ballot requests. They can sometimes design ballots, decide the number and location of polling places and take part in the counting of ballots. More often than not, these workers are career bureaucrats who serve an essential, though typically overlooked role, in ensuring elections run smoothly.

Election workers are no longer under-the-radar. After the 2020 election, Trump and his allies have remained focused on uncovering widespread voter fraud that simply does not exist. The sweeping belief that the election was stolen has meant that the most fervent Trump supporters are convinced that election workers — especially in the cities and towns where Democrats won big — are illegally rigging election results. It’s a patently false belief, but one that has nonetheless fueled a scary trend of threats and harassment.

In a recent hearing in the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, New Mexico Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver (D) testified: “During the 2020 election cycle, I was doxxed, my life was threatened and I had to leave my home for weeks under state police protection.” In early December 2020, protestors carrying guns and American flags surrounded the home of Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson (D), accusing Benson of ignoring voter fraud and certifying President Joe Biden’s win in the state.

At the Senate hearing, however, Benson instead took the opportunity to highlight the experience of others in her state: “Detroit City Clerk Janice Winfrey was sent photos of a dead body with a message to imagine that body as her daughter,” Benson described. While the secretary of state is the chief elections official in most states, and consequently the most visible, “Big Lie” extremism spared no jurisdiction, no matter how local.

The Republican city commissioner of Philadelphia, a worker in Arizona’s Maricopa County Elections Department, staff in the Nevada’s secretary of state office, the executive director of the Colorado County Clerks Association and an election administrator from Tarrant County, Texas. Recently, in a deep-red Texas county, nearly all the staff in the elections office resigned after harassment and overwhelming pressure. The anecdotes that have emerged in the past year and a half represent only a sliver of the total incidents. A Brennan Center survey revealed that one in six election officials have experienced threats and one in five indicated that they are likely to leave their jobs before 2024.

Swing states and states that have criminalized election administration are of particular concern.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Election Threats Task Force, officials in states with close elections and postelection contests were more likely to receive threats. Of the total potentially criminal threats, 58% were in states like Arizona, Georgia, Colorado, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Nevada and Wisconsin.

In addition to threats by private citizens, some state governments are piling on more stress. Since 2020, 12 states have enacted 35 new criminal penalties targeting election officials. For example, a 2021 Iowa law prohibits county auditors from sending mail-in ballot applications and pre-filling certain information. Iowa has allowed no-excuse vote by mail since 1990, and for many years, some county auditors would proactively send mail-in ballot applications to their residents. They now face new fines for working to boost turnout and simplifying one step in the complicated voting process.

Unnecessary penalties contribute to the psychological environment that well-meaning administrators are somehow doing something illegal and nefarious in otherwise routine work. David Becker, the executive director of the Center for Election Innovation and Research, told the States Newsroom that election officials are exhausted. “We’re going to see the potential of losing an entire generation of professional election officials, which is bad in and of itself because we rely on them to run smooth elections, but who replaces them?”

Certain laws and DOJ action can help, but this problem won’t go away as long as the “Big Lie” is alive and well.

A group of bipartisan U.S. senators recently introduced the Enhanced Election Security and Protection Act, an important bill that was overshadowed by accompanying legislation. The bill would double the penalty for individuals who threaten or intimidate election officials, poll watchers, voters or candidates. In April, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown (D) signed House Bill 4144 into law, changing the misdemeanor classification for harassing election workers to increase the possible penalties. Additionally, the new law permits election workers to withhold their home addresses from public disclosure. In Oregon, the U.S. Senate and elsewhere, the common thread among proposed legislation is to increase penalties for harassment and threats.

Last summer, the DOJ launched a task force to “receive and assess allegations and reports of threats against election workers” and to partner with field offices throughout the country to “investigate and prosecute these offenses where appropriate.” Investigation, prosecution and increased penalties are a worthy policy goal to ensure accountability, but they nevertheless fail to address the root cause of the issue — powerful leaders who continue to spread false claims about voting and election results.

Toulouse Oliver aptly summarized it: “We will not stop such threats until the lies stop.”