Do Redistricting Reforms Lead to Fair Maps?

Over the last decade, many states adopted reforms changing how congressional redistricting is done. One major goal of these reforms is to reduce partisan gerrymandering to ensure maps aren’t drawn to favor one political party over the other — in other words, to ensure fair maps. But enacting a reform is one thing, and successfully producing a fair congressional map is entirely another. In today’s piece, we’re looking back on six states that enacted redistricting reforms — Colorado, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia — in the last decade to see how successful each reform was (or not) at leading to a fairer map.

How can you tell if a congressional map is fair or not?

Judging the fairness of a congressional map isn’t as simple as just looking at it — just because a map has nice, compact districts doesn’t mean it’s good or fair. Thankfully, political scientists and other experts have developed four different statistical metrics that try to objectively measure how biased a congressional map is toward a political party:

- The efficiency gap measures the extent to which district lines “crack” and “pack” one party’s voters more than the other — the smaller the gap, the fairer the map;

- The partisan bias measures the difference between each party’s share of districts in a hypothetical tied election — under a fair map, this difference should be close to zero;

- The mean-median difference measures the difference between a party’s median vote share and its mean vote share — under a fair map, these numbers shouldn’t diverge significantly;

- The declination measures how much importance a map places on the threshold for victory (usually 50% of the vote) — an unfair map’s districts will be distributed asymmetrically around the threshold.

Each of these metrics can give you an estimate of how tilted a map is towards one political party. Taken together, they can give us a general sense of a map’s fairness. To evaluate the impact of redistricting reforms, we can compare the map a state had pre-reform to the map the state enacted after reforms across all four metrics. For each state, we compare the map that will be used this year with the map the state used in the 2012 elections, as several of the states used multiple maps in the last decade due to court intervention. The Campaign Legal Center provides a website where you can measure congressional maps on all four metrics. All the data in this piece come from there.

Of course, partisan fairness isn’t the only part that matters in a congressional map. Other factors, like preserving communities of interests or ensuring minority representation, are important and these four partisan fairness metrics cannot tell us anything about how well a map accomplishes those goals. Partisan fairness is ultimately only one of several factors that need to be weighed when evaluating a map.

States that adopted commissions.

One type of redistricting reform that has gained popularity recently is putting map-drawing power in the hands of a commission — multiple states adopted commissions in the last decade. These commissions come in many different flavors — some are bipartisan and divided equally between the two major parties while others include political independents, and some are made up of elected officials while others are made up of citizens. Commissions are often seen as the gold-standard redistricting reform; Democrats’ For the People Act, for example, mandated the use of independent commissions for congressional redistricting in all states.

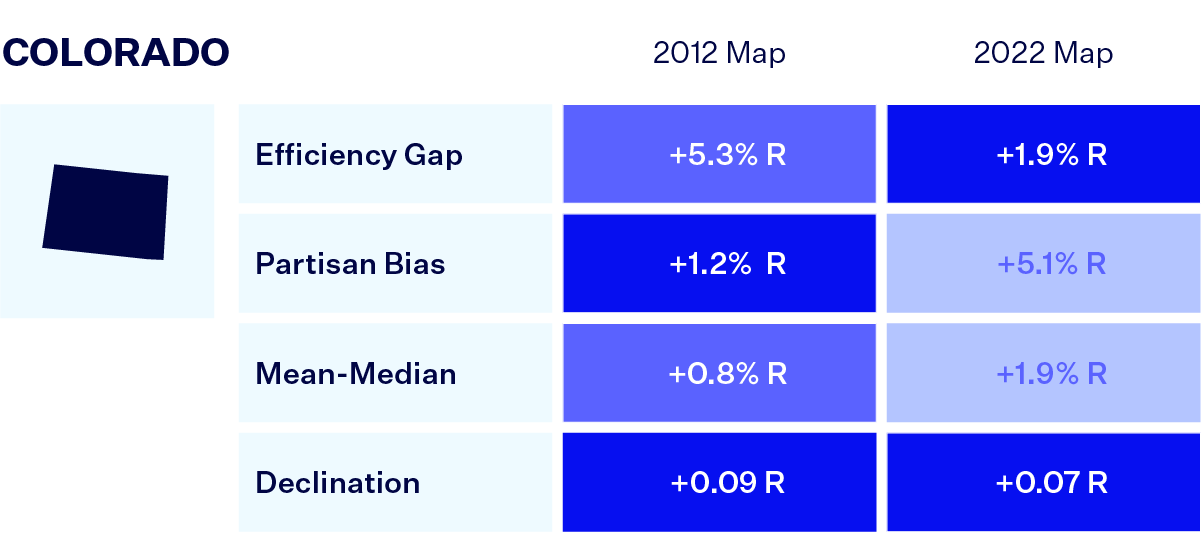

Colorado

Colorado’s 2012 map was enacted by a court after the state Legislature failed to pass a plan.

In 2018, Colorado voters approved Amendment Y, which created an independent commission to handle congressional redistricting, which was previously handled by the state Legislature. The commission consists of 12 citizen members chosen by a panel of judges: four Republicans, four Democrats and four unaffiliated voters. A map must earn the support of at least eight commissioners — including at least two of the unaffiliated commissioners. The amendment also added several requirements for new districts. The commission approved the state’s new congressional map on Sept. 28, 2021 and the state Supreme Court okayed it on Nov. 1, 2021. For more about what happened in Colorado, read our “Redistricting Rundown: Colorado.”

The map passed by Colorado’s commission actually scores worse on some metrics of partisan fairness than the court-enacted 2012 map did. Although the map has a smaller efficiency gap and declination, it is more skewed toward Republicans under the partisan bias and mean-median measures.

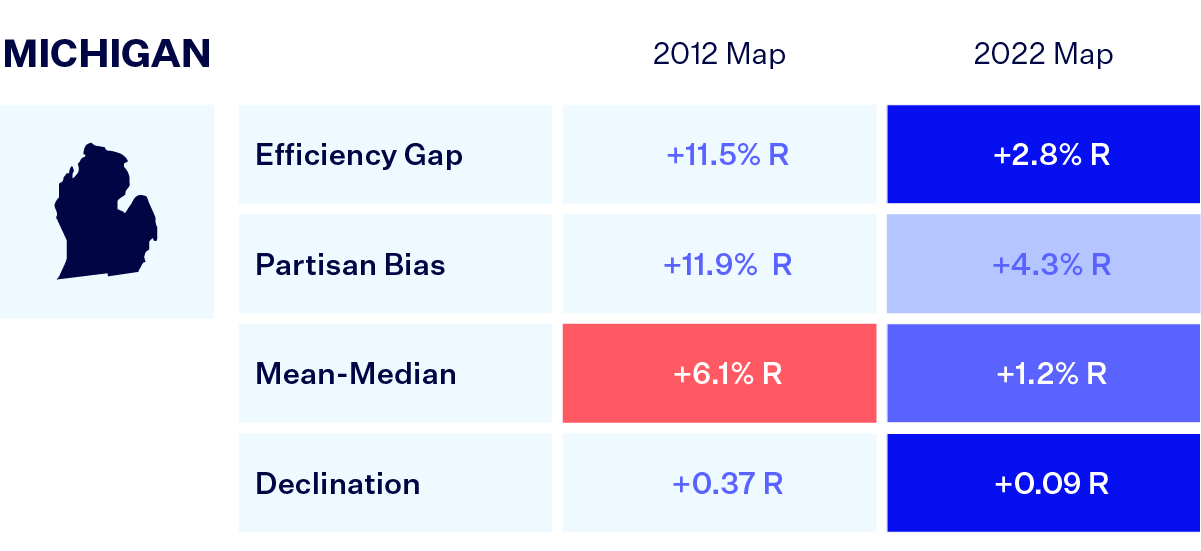

Michigan

Michigan’s 2012 map was enacted by Republicans, who controlled both houses of the Michigan Legislature and the governorship at the time.

Like Colorado, Michigan voters approved the creation of a redistricting commission in 2018. Michigan’s commission consists of 13 members randomly selected from an applicant pool: four Democrats, four Republicans, and five independents or members of third parties. A map must earn the support of seven commissioners — including at least two Democrats, two Republicans and two of the other five. Michigan’s commission approved a new congressional map on Dec. 28, 2021 after soliciting feedback and considering various different proposals throughout last fall.

Michigan’s new congressional map, while still slightly biased toward Republicans, is much fairer than the 2012 map across all four metrics.

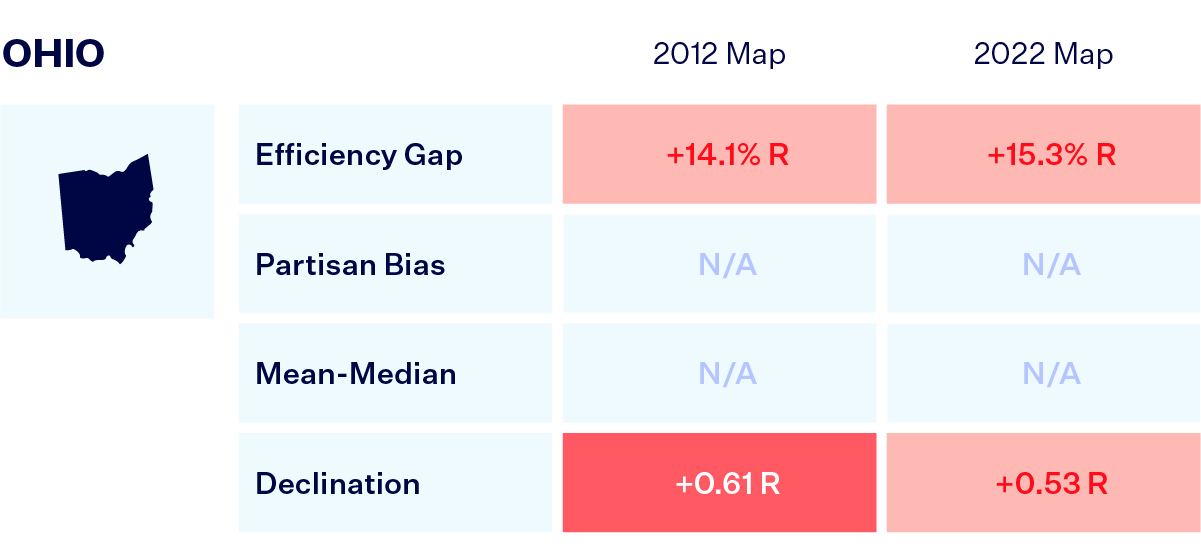

Ohio

Ohio’s 2012 map was enacted by Republicans, who fully controlled the redistricting process.

In 2018, Ohio voters approved an amendment to congressional redistricting. Ohio’s reform is a little more complicated than that of other states in this piece. Rather than moving the responsibility of redistricting completely to a commission, the amendment splits the responsibility between the Ohio Redistricting Commission (ORC) and the General Assembly. The General Assembly has the first opportunity to draw new congressional districts. If it fails to adopt a map with at least 60% support and the backing of at least half of the minority party, responsibility falls to the ORC. If the ORC — which consists of the governor, secretary of state, auditor and two members appointed by each party in the General Assembly — fails to adopt a map by a bipartisan vote, the General Assembly gets another crack at map drawing. If it adopts a map without sufficient support of the minority party (currently Democrats), however, the map is only in effect for four years and is required to not disfavor any political party.

Unfortunately, Ohio Republicans never really tried to comply with this reform. The General Assembly didn’t even bother trying to pass a map with the required bipartisan threshold before the first deadline and the ORC missed its deadline to pass a bipartisan map as well. The General Assembly then passed a map by simple majority on a party-line vote — a map the Supreme Court of Ohio struck down for unduly favoring Republicans in violation of the state Constitution. The General Assembly missed the deadline given by the court and the ORC approved a revised congressional map on March 2, 2022 that barely differed from the overturned one. While the state Supreme Court could still rule the revised map unconstitutional, it likely won’t be in time for the 2022 elections — Republicans seem to have successfully waited out the clock to enact a partisan gerrymander.

This year’s map is just as partisan toward Republicans as the 2012 map. While the state’s reform could eventually prove successful, it would only be thanks to intervention by the state Supreme Court, as the other relevant actors have shown no interest in complying.

Virginia

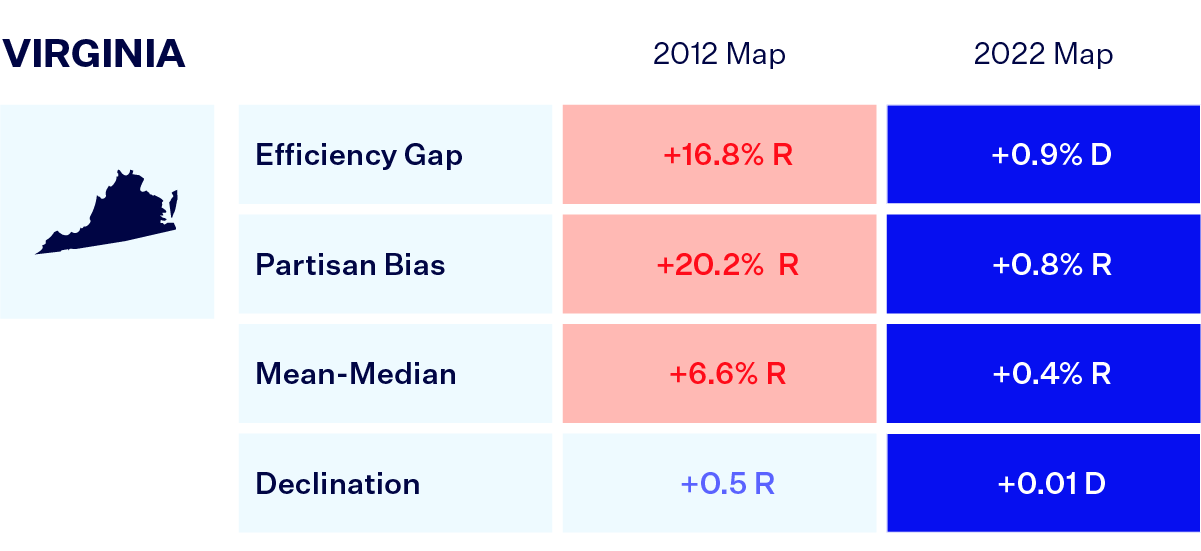

Virginia’s 2012 map was passed by Republicans, who fully controlled redistricting at the time.

In 2020, Virginia voters approved the creation of a bipartisan redistricting commission. The commission consists of 16 members — eight citizens selected by a committee of judges and four legislators from each house of the Virginia General Assembly, equally divided between the two major parties. A map must earn the support of at least six citizen commissioners and at least six legislative commissioners. During the commission’s first round of redistricting, the even partisan split quickly bogged down the commission in partisan disagreements — it ultimately failed to pass any maps and the state Supreme Court took over redistricting. The court appointed two special masters and adopted a new congressional map on Dec. 28, 2021.

On one hand, Virginia’s reform was clearly unsuccessful in that the commission completely failed to accomplish its one and only task. On the other hand, the backup role given to the state Supreme Court led to the adoption of a map that is much fairer than what politicians enacted for the 2012 election. In fact, the Virginia Supreme Court’s adopted map, across all four metrics, is one of the fairest maps discussed in this piece.

States where courts intervened in map drawing.

Another way a state can reform redistricting is through judicial intervention. While the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that partisan gerrymandering is beyond the reach of federal courts, it left the door open for state courts to overturn partisan gerrymanders under state constitutions. Two states that have done exactly this in recent years are North Carolina and Pennsylvania.

North Carolina

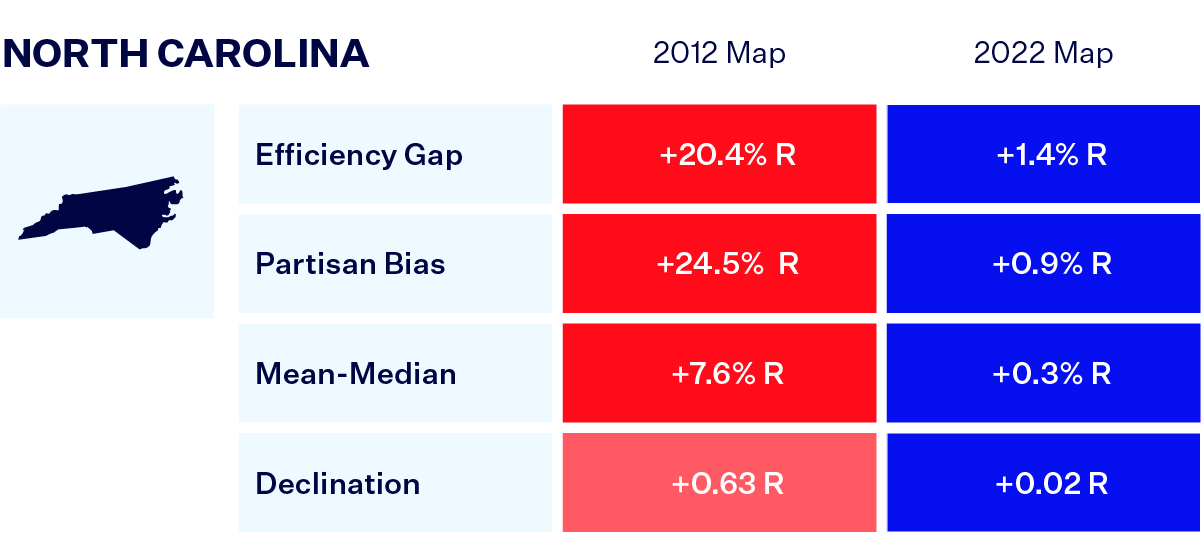

North Carolina’s original 2012 map was passed by the Republican-controlled Legislature (North Carolina governors cannot veto redistricting maps).

In 2019, a state court in North Carolina found that the congressional map drawn by the Republican-controlled Legislature in 2012 was a partisan gerrymander that violated the North Carolina Constitution. Rather than appeal the decision, the Legislature opted to redraw the map just for the 2020 elections, which led to two additional Democratic-leaning districts. However, the question of whether the state constitution bans partisan gerrymandering was never definitively answered.

The same plaintiffs in the 2019 case challenged the map passed by the Republican Legislature in November 2021. In February 2022, the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the North Carolina Constitution prohibits partisan gerrymandering and overturned the Legislature’s congressional map. The court gave the Legislature the opportunity to pass another map and invited the plaintiffs in the case to submit their own proposals; the court eventually adopted a map modified by two special masters. This map will only be used for 2022, after which the Legislature could pass another map to be used in future elections.

North Carolina’s 2012 map was highly biased towards Republicans. The court-enacted 2022 map is much fairer across all four metrics.

Pennsylvania

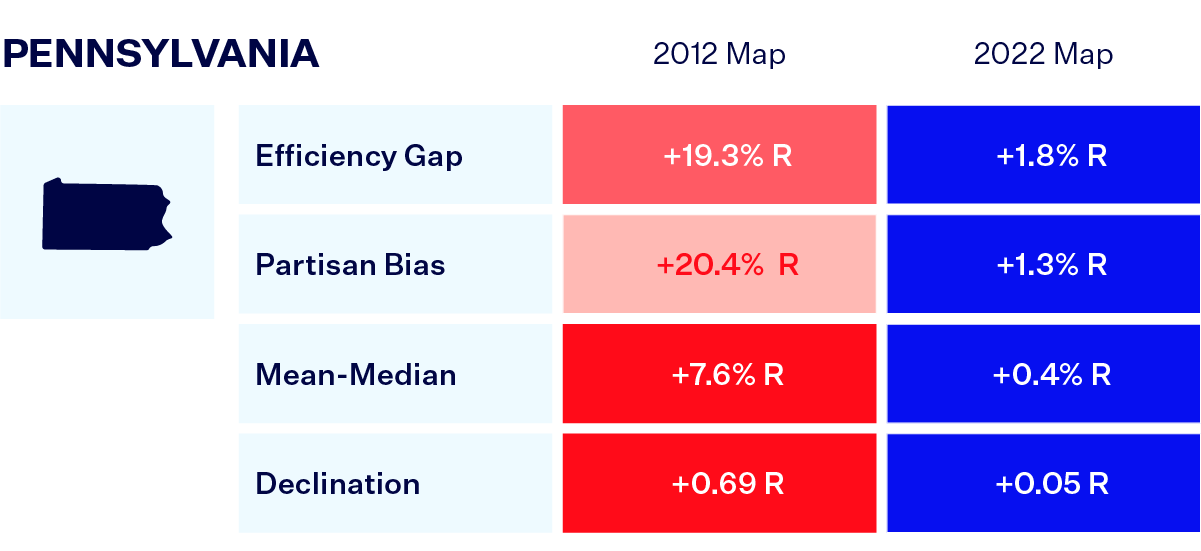

Pennsylvania’s 2012 map was adopted by Republicans, who fully controlled redistricting.

In 2018, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court overturned the 2012 congressional map, finding that the map represented an extreme partisan gerrymander in violation of the Pennsylvania Constitution. The court then enacted a congressional map drawn by a special master when the Legislature and the governor failed to pass one of their own.

This year, after the Legislature and governor failed to agree on a new congressional map, the state Supreme Court stepped in again. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ultimately adopted a congressional map drawn by an outside redistricting expert and proposed by the plaintiffs in the impasse case Carter v. Chapman, finding it best adhered to traditional redistricting criteria and complied with the state constitution’s ban on partisan gerrymandering.

Like North Carolina, Pennsylvania’s 2012 map was highly biased toward Republicans and the court-adopted 2022 map is much fairer.

Here are the key takeaways of our analysis of redistricting reforms.

1. In general, reforms work.

The majority of the states examined in this piece are going into the 2022 elections with fairer maps than they had in 2012. For the most part, reforms worked — and Ohio might still get a fair map in time for 2024.

2. Not all commissions are created equally.

A commission doesn’t guarantee a fair map and it matters how the commission is designed. In general, commissions that are made up of citizens and include independents and/or unaffiliated voters (Colorado and Michigan) were more successful than bipartisan commissions or commissions that included politicians (Ohio and Virginia). Just having a commission is not enough — reformers need to think carefully about how the commission is designed, who sits on the commission and how it will work in practice.

3. Courts appear better at drawing fair maps.

For the most part, courts seem to be the best at drawing fair maps. The maps enacted by the North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Virginia Supreme Courts are the fairest maps overall, and the court-enacted 2012 Colorado map is by some measures fairer than the Colorado commission’s 2022 map. Reformers should consider giving courts a greater role in redistricting, either as a backup to commissions like in Virginia or to review maps like in Ohio. Using state courts to enforce bans on partisan gerrymandering in state constitutions, as in North Carolina and Pennsylvania, is also a fruitful avenue for reform that doesn’t require the creation of commissions.

4. Judicial elections matter.

Finally, the analysis underscores how important judicial elections are. The court decisions in North Carolina and Ohio this year were both 4-3 decisions. Had a single judicial election in either state gone differently, North Carolina would likely still have a highly biased congressional map and Ohio Republicans would likely have gotten away with their attempt to gerrymander the state. Both states will have judicial elections this year that will decide the course of future redistricting litigation. State courts can serve as essential bulwarks against partisan gerrymandering, but it depends entirely on who is elected to them.