Redistricting Rundown: Colorado

Like Ohio, the focus of our first redistricting rundown, Colorado is using a brand new method for redrawing its legislative and congressional districts. Thanks to Amendments Y and Z, approved by voters in 2018, Colorado is using two separate independent commissions to redraw districts. However, Colorado’s new congressional map prioritizes competitive districts at the expense of Latino representation and an accurate reflection of the state’s baseline partisan composition. A state that went for President Joe Biden by a double-digit margin could send an evenly split congressional delegation to Washington. While often hailed as commonsense solutions to the problems raised by redistricting, it turns out commissions can end up drawing maps with many of the same deficiencies as ones drawn by politicians.

Colorado voters approved a new redistricting commission in response to concerns about partisan gerrymandering.

In the 2018 elections, Colorado voters approved Amendments Y and Z to the state constitution to reform the state’s redistricting process. Previously, congressional districts were drawn by the state Legislature and legislative districts were drawn by a panel of 11 members appointed by the governor, Colorado Supreme Court chief justice and legislative leaders. Critics argued that partisanship played too big of a role in redistricting and a coalition of politicians and activists across the political spectrum joined together to push for the amendments, including then-Gov. John Hickenlooper (D), former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder (D), former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger (R) and actress Jennifer Lawrence.

Both amendments put control of redistricting in the hands of two independent commissions — one for state legislative maps and one for the congressional map. Each commission has 12 members: four Republicans, four Democrats and four unaffiliated voters. New districts require a supermajority vote of eight in favor — including at least two of the unaffiliated members. Any voter in Colorado (with some exceptions) can apply to be a commissioner. The application pool is then whittled down through a combination of random selection and screening by a three-judge panel with limited input from state political leaders. Commissioners must reflect the state’s racial, ethnic, gender and geographic diversity, with at least one from each congressional district and at least one member from Colorado’s Western Slope — the portion of the state west of the Continental Divide.

Once the commissioners are chosen, a nonpartisan staff helps the commissions draw new maps. The staff first draws up a preliminary map. From there, the commissions hold public hearings throughout the state to collect feedback, which the staff can use to amend the preliminary map before settling on a final proposal. When drawing maps, staff must first ensure districts are of equal population and geographically contiguous. Then, in descending order of importance, the districts must comply with the Voting Rights Act, keep “communities of interest” and political subdivisions intact where possible and draw compact districts. Only after these requirements are satisfied can the commission attempt to maximize the number of competitive districts. The commissions are also prohibited from drawing districts to protect incumbents or give a party an advantage.

Despite Colorado’s increasingly blue lean, the congressional commission approved a map that could result in an evenly split congressional delegation.

Colorado’s commissions began working on new maps this summer after the U.S. Census Bureau released preliminary population estimates and apportionment data. The Independent Congressional Redistricting Commission released a preliminary congressional map on June 23 and the Independent Legislative Redistricting Commission released preliminary state House and Senate maps on June 29. Both commissions then solicited feedback from residents and advocacy groups and released various updated draft versions in anticipation of final votes to adopt one plan or another.

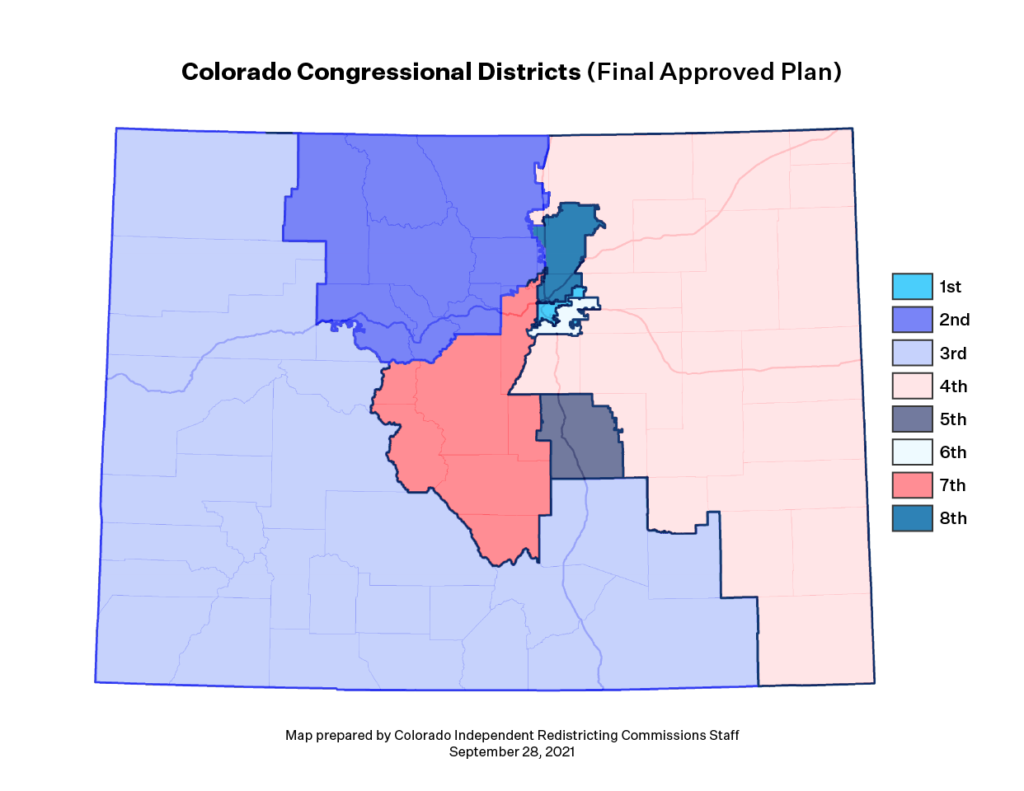

On Sept. 28, the Independent Congressional Redistricting Commission approved the new congressional districts below by an 11-1 vote after multiple rounds of voting and hours of debate. The map creates four Democratic-leaning districts (the 1st, 2nd, 6th and 7th Congressional Districts), three Republican-leaning districts (the 3rd, 4th and 5th Congressional Districts) and a new highly competitive district north of Denver (the 8th Congressional District). This map could theoretically lead to an evenly-split congressional delegation after 2022, with each party holding four seats — despite Colorado going blue in every presidential election since 2008 and Biden winning the state by the largest margin in the two-party vote since 1984.

The congressional map is now being reviewed by the Colorado Supreme Court, which has until Nov. 1 to decide whether to approve the map or send it back to the commission for revisions. The court is accepting briefs on the congressional map until Oct. 8, with oral arguments scheduled for Oct. 12.

Meanwhile, the Independent Legislative Commission is expected to adopt final state House and Senate maps by Oct. 15.

Multiple groups object to the new congressional districts for prioritizing competitiveness at the expense of Latino representation.

Multiple groups have already indicated plans to submit briefs challenging the new congressional districts to the state Supreme Court. In particular, several Latino advocacy groups argue the districts fail to adequately represent the state’s Latino population. In a statement, the Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy and Research Organization (CLLARO) contends that the commission “disregarded the will of the voters by prioritizing an arbitrary competitiveness target over communities of interest.” Likewise, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and Campaign Legal Center also objected to the plan for inadequately representing Latinos, noting that a district boosting Latino electoral power could have been created in the southern part of the state. “Our concern is that the chosen map violates the Colorado Constitution because it needlessly dilutes the electoral influence of Colorado’s Latino voters,” said Corey Goldstone, a spokesman for the Campaign Legal Center.

LULAC also raised concerns with the commission plan’s competitive 8th Congressional District. Although the district is configured to be the most Latino in the state, by joining Latino voters with rural white voters the commission’s plan “creates a significant risk that white bloc voting would result in general election victories by candidates opposed by Latino voters.” In the last few statewide elections, the candidate preferred by the Latino community in the district was defeated by the candidate preferred by the white population, raising the possibility in next year’s congressional election that the Latino community’s preferred candidate would also lose the district. LULAC concludes that “to the extent District 8 is intended to further the Colorado Constitution’s criterion that the Commission should ‘to the extent possible, maximize the number of politically competitive districts’…it is unlawful to accomplish that goal by making the district with the largest Latino population into the facade of a Latino opportunity district.”

The Colorado Democratic Party and Colorado Common Cause also expressed concern over how the commission considered political competitiveness, which both groups suggest may have been overemphasized. “We are thankful to the commission for its hard work on this map, but remained concerned that competitiveness came almost exclusively at the expense of Democrats,” a spokesman for the Colorado Democratic Party said. “The commission spent a lot of time, both last night and throughout their process, talking about competitiveness,” said Amanda Gonzalez, executive director of Colorado Common Cause, noting that competitiveness is the lowest constitutional priority. “We don’t have any indication that it was done in a robust way and we don’t have a public report.”

Commissions do not automatically solve every redistricting dilemma.

Redistricting and the creation of fair maps involves multiple competing priorities like compactness, competitiveness, minority representation and respecting existing communities. The thorny dilemma at the heart of redistricting is that these goals are often in tension with each other. As demonstrated by Colorado, prioritizing competitiveness can lead to a redistricting plan that does not accurately represent the underlying partisanship of a state and can come at the expense of minority representation. The map approved by Colorado’s Independent Congressional Redistricting Commission reflects the simple fact that commissions aren’t guaranteed to resolve these tensions better than any other redistricting method.