Creating Security Issues, One Election Conspiracy at a Time

Top members on the legal team of former President Donald Trump improperly shared sensitive voting machine information with a host of conspiracy theorists and right-wing commentators, as revealed in a recent Washington Post report. A newly obtained video shows how a local elections official escorted two GOP operatives into the Georgia county’s office on the same day as the voting machine breach.

Implicated in this several state effort is Matthew DePerno, the GOP nominee for Michigan attorney general, who was part of a group of individuals who misrepresented themselves to election officials in order to access voting equipment, which the group then tested and tampered with. DePerno, allegedly one of the “prime instigators of the conspiracy,” could be elected to statewide office this fall.

Another GOP candidate, Mesa County elections clerk Tina Peters, created a similar security breach in Colorado. Peters has been indicted on 10 felony and misdemeanor charges for helping an unauthorized person make copies of sensitive voting machine hard drives. Peters then ran for the Republican nomination for Colorado secretary of state in 2022 (she lost in June, but continued to demand recounts despite a 14 percentage point disadvantage).

If experts repeatedly stated that the 2020 election was the “most secure in American history,” what’s the deal with this frenzy about voting machines? With a range of voting technology used across the country, there are legitimate vulnerabilities that must be addressed. These concerns, however, just aren’t the conspiracies pushed by the far-right.

What election equipment do we rely on to vote?

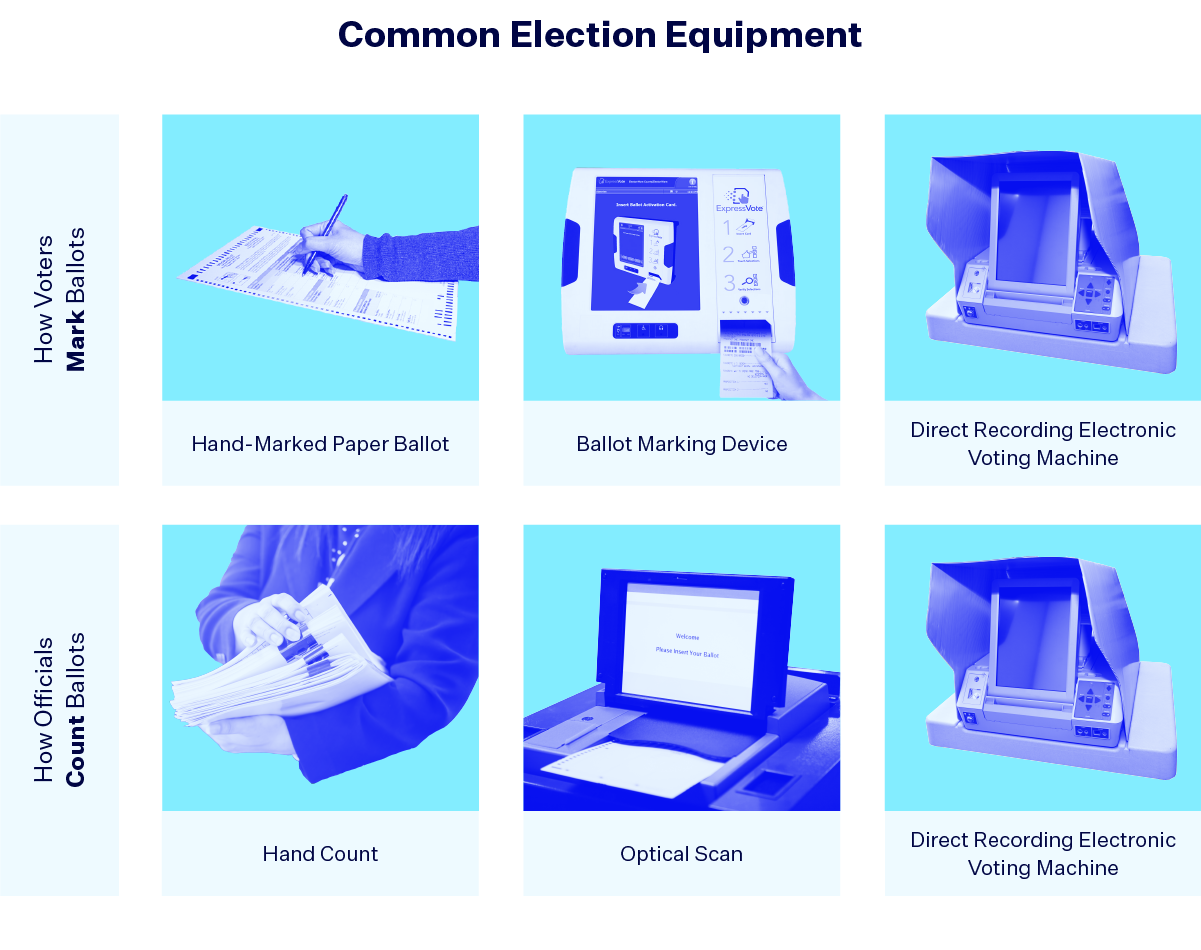

There are two main points in the voting process where election technology comes into play — marking ballots and tabulating (or counting) ballots.

For marking ballots, the voting method most ingrained in our psyche is a hand-marked paper ballot. However, there are two other distinct types of voting machines you may encounter at a polling place. Ballot marking devices (BMD) use an electronic system to mark a ballot, such as buttons or touch screens. But instead of storing the vote in the device’s memory, the BMD prints a paper ballot with the voters’ choices. The marking experience for the voter is very similar with both a BMD and a direct recording electronic (DRE) voting machine, but in contrast, the vote is stored in the DRE’s memory, no paper ballot is printed and the vote is transmitted electronically to a central report.

There are three main ways to tabulate ballots. A DRE machine internally counts the results electronically and there are two main methods when paper ballots are involved — a hand count or optical scan. Optical scan devices read ballots that were marked by filling in an oval or box-shaped shape, similar to the way a machine scores standardized tests.

Voting technology can have vulnerabilities. But it’s not what conspiracy theorists think.

Each state uses a different combination of equipment, with accessible options required by federal law to be available to voters with disabilities. Other types of equipment have come and gone with time. Punch cards became popular in the second half of the twentieth century, but after they caused major issues in the close 2000 presidential election, the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA) banned the use of punch cards in federal elections. HAVA also provided funds for election offices to update outdated equipment, leading to an increase in DREs.

However, these purely electronic systems soon revealed their own shortcomings. If any issue arises with a paperless DRE machine, there is no way to verify the information stored within it and whether the machine is functioning correctly. Consequently, there has been an increase in DREs that have a feature that maintains a paper trail. In fact, election security experts largely agree that involving paper ballots at some point in the process is an essential security measure. In 2020, an estimated 93 percent of American voters in 2020 used some type of paper ballot, whether hand-marked or BMD printed.

Election infrastructure expert Lawrence Norden concluded in a 2015 report: “The key challenge facing American elections as voting machines reach the end of their lifespans is that, in too many instances, no level of government believes it should be responsible for maintaining or replacing them.” Now, compound that with the 2022 trend of Republicans lawmakers banning private funding for elections, bankrupting our under-resourced election administrators even further and providing little incentive to upgrade election infrastructure.

“Big Lie” proponents are creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of unauthorized access that is actually endangering our democracy.

In contrast to the legitimate concerns about aging technology, fervent Trump supporters and “Big Lie” proponents have rallied around a host of unfounded claims. Trump attorneys Sidney Powell and Rudy Giuliani, along with MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell, are currently facing a billion dollar defamation suit from Dominion Voting Systems, a manufacturer of voting equipment used in 28 states. The Trump group has repeated harmful assertions that Dominion machines somehow changed “a million” votes from Trump to now-President Joe Biden, and helped steal the election. Powell has also claimed that some of Dominion’s software was created “at the direction” of former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and that the company has corporate ties to big Democratic donors, all of which are false.

An in-depth review by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) of Dominion’s ImageCast X devices (a type of BMD) revealed several technical flaws. However, the advisory emphasized that “CISA has no evidence that these vulnerabilities have been exploited in any elections.”

What’s worse is that security breaches are now taking place, created by those who tamper with machines in the name of “investigating” the 2020 election. For example, when Peters helped unauthorized individuals gain access to equipment in Colorado, machine information and secure passwords were later shared online with other election conspiracy theorists. The county had to replace all the compromised machines.

In Alabama, a group of Republicans filed a lawsuit challenging the use of optical scanners across the state. The plaintiffs argue that these machines subject “voters to cast votes on an illegal and unreliable system” and ask for a hand count of the November 2022 election. (Hand counts are an important tool for recounts or confirming machine accuracy, but if used as a primary tallying method, they can add human error and inaccurate standards into the process.) Even Alabama’s Republican attorney general asked the judge to throw out the case. A similar lawsuit tried to end Arizona’s use of electronic voting machines, specifically optical scanners and Dominion’s BMD technology. Filed by the extreme GOP nominees for Arizona secretary of state and governor, Mark Finchem and Kari Lake, the lawsuit was recently dismissed by a judge who called the claims “vague,” “speculative” and ultimately amounted to “conjectural allegations.” Just last week, a New Hampshire man sued the state, trying to outlaw electronic ballot counting technology.

In contrast to these “speculative” lawsuits, voting technology has, in general, helped more than hurt the accuracy and efficiency of voting and tabulating results. While aging infrastructure and underfunding of election administration are serious concerns, the claims raised by far-right activists aren’t based in that sphere of reality. Instead, these individuals create the very security breaches they are “trying” to protect against.