No Lawsuit Is Too Trivial, No Action Is Too Small

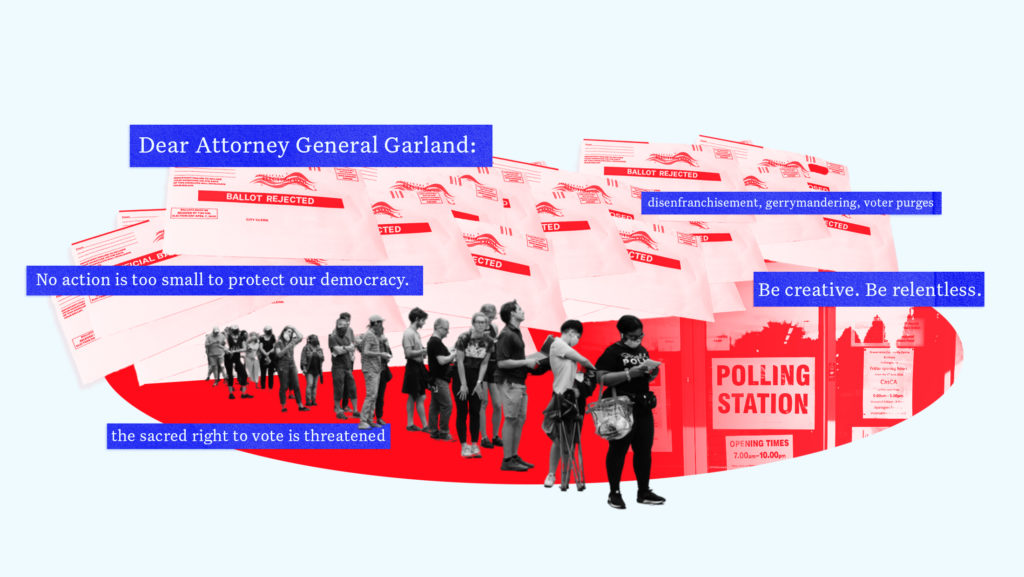

Last year, Republican state legislatures began a full-scale assault on voting rights. Now, the people targeted by those laws are urgently asking for help. 44 members of the Congressional Black Caucus recently wrote a letter to the U.S. attorney general urging him to increase the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) efforts to protect voting rights in court.

“The future of democracy is at stake,” the letter began. “Citizens across the country face an onslaught of antidemocratic laws designed to restrict access to the ballot, diminish the power of voters of color, and overturn the results of fair elections.”

The letter’s authors describe the new voter suppression laws as “racist and partisan”— targeting minority voters because of their race and Democratic voters because they are Democrats. Black voters, the group most loyal to the Democratic Party, face the greatest threat to their rights.

The letter was unsparing in its call to action:

“Be creative. Be relentless. Be unapologetic in your commitment to do whatever it takes to ensure that every American has their vote counted no matter how they look or where they live. No lawsuit is too trivial when it comes to the voting rights of citizens.”

The members of Congress were joined last week by the elected leadership of Harris County, Texas — the largest, most diverse, and Democratic county in the state. In their own letter, these Texas officials also urged the DOJ to take an aggressive, comprehensive, uncompromising approach to protect voting rights in court.

“Our message today is simple: please exhaust every legal option available to ensure that each eligible voter in Harris County and the State of Texas has their vote counted. No action is too small to preserve our democracy.”

These statements, and the sentiment of frustration behind them, illustrate a growing divide over the threat of voter suppression and the most effective ways to combat it.

On one side are those who urge a go-slow court strategy concerned first and foremost with avoiding bad court precedent. Supporters of this approach, many of whom are academics and journalists, discount the significance of voter suppression laws on the outcome of elections and see voting rights cases primarily through the legal or political lens of what it means for the development of the law or who wins a particular election.

On the other side are minority and young voters who are targeted by these laws, as well as the advocates and elected officials who serve them. For voters, restrictions of absentee ballots, curtailing early voting hours and long polling place lines are not legal doctrines or political science theories — they are practical barriers to participating in democracy.

For a voter facing disenfranchisement due to a new law, whether a particular voting rights case creates favorable or unfavorable precedent is largely beside the point. That voter wants to vote, not serve as the topic of a law school debate. Indeed, all too often we fail voters when we let debates over future jurisprudence, rather than the actual voters disenfranchised by restrictive voting laws, drive litigation decision making.

The reason for the disconnect is obvious. For too many elites, voter suppression laws are theoretical and remote. They almost certainly have state-issued identification and rarely find themselves in hours-long lines waiting to vote. Their ballots are rarely rejected or challenged, and when they are, this group of voters has the time and resources to take corrective action. In short, too many “experts” discount the effects of voter suppression because while they read about the challenges posed by new laws, they do not experience them firsthand.

Take, for instance, the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Brnovich v. DNC. Following the gutting of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA), Arizona enacted a new law that intentionally discriminated against Black, Latino and Native American voters. Passage of the law, which prohibited third-party ballot collection, was predicated on a racist video depicting a Latino man engaging in lawful ballot collection.

When the Supreme Court upheld the racist law, nearly all the legal and political commentary was about the future impact the decision might have on future VRA cases. Absent the media coverage was the fact that for many living on Native American reservations, without mail service, third-party collection was the only way for them to return their ballots. Also ignored was the racist origin of the law and the fact that for many minorities in Arizona, the ruling would effectively deny them the right to vote.

As Republicans enact more suppressive laws and the courts hear more cases, the contrast between seeing voting litigation as the development of legal doctrine versus vindicating the rights of real voters is stark and the disagreements are boiling over.

That is why the extraordinary letters from members of Congress and Harris County officials are so important. These elected officials made clear that like their constituents, they are not prioritizing the development of legal precedent, but are demanding more litigation to fight for the right to vote.

The authors of these letters have no illusions that every lawsuit will succeed. They no doubt understand that the consequences of losing cases could mean bad precedent in the future. But they see the threat to voting rights today as justifying that risk, as they write: “No lawsuit is too trivial,… no action is too small.”