In a Major Victory, the Supreme Court Didn’t Break Democracy

When Abha Khanna stepped up to the U.S. Supreme Court lectern last fall, she faced a daunting task: convincing a majority of the justices to reject Alabama’s challenge to Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). None of the six conservative justices appeared likely to join the three liberals in upholding this historic civil rights law. Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito were never going to save the VRA.

Ten years earlier, Chief Justice John Roberts had written the Shelby County v. Holder (2013) decision that gutted Section 5 of the VRA. That provision required states and localities with a history of racial discrimination in voting to have any new voting law or practice reviewed and approved prior to going into effect. Roberts assured us that times have changed, and that provision was no longer needed. Since Shelby County, Justices Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh have joined as untested Trump appointees, moving the Court even further to the right.

As she began to speak, it was clear that Khanna had a plan — convince the conservative justices that messing with Section 2 was not worth it. She began, “Alabama seeks to upend the Section 2 standard that has governed redistricting for nearly 40 years.” She pointed out that changing Section 2 jurisprudence would not only be bad for minority voters, but for the courts as well. In short, she argued: “This Court should reaffirm its established Section 2 standard because it works.”

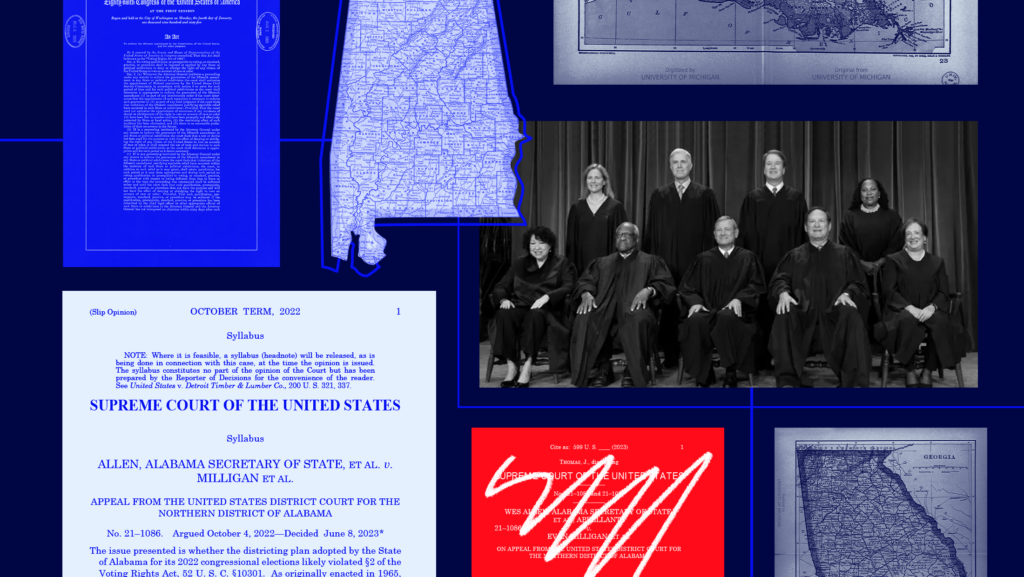

The Allen v. Milligan case began in 2021 when Alabama redrew its congressional map and ran afoul of Section 2. Even though Black citizens compose 27% of the population of the state, the Legislature enacted a map with only one district in which Black voters could elect their candidate of choice. After a hearing, a staunchly conservative three-judge panel unanimously held that Section 2 required Alabama to create a second Black opportunity district.

When Alabama appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, the state had reason for optimism. In the decade since Shelby County, the Court has become markedly more conservative. In its most recent case interpreting Section 2 as it relates to voting laws, the Court’s majority adopted a cramped view of the VRA’s protections. And, most importantly, shortly after the three-judge panel ruled against Alabama, the Supreme Court paused that victory until it could decide the case in full.

This past Thursday morning, Alabama’s hope turned into despair when the Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision. Ten years after Roberts struck down Section 5 in Shelby County, he spared a different critical provision of the VRA. Joining the Chief Justice were the Court’s most liberal members — Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson — and Kavanaugh.

By reaffirming 40 years of precedent, the Court signaled to lower courts to take Section 2 claims seriously.

In many respects the opinion is remarkable for being unremarkable, even mundane. It is an opinion that any number of more liberal justices could have written during the last 40 years. Given the Chief’s normally sharp writing style and conservative instincts, the tone of the opinion confirms that it is intended to break little new ground.

So, what happened?

At a time when the conservative Court is dispensing with past precedents like used tissues, this opinion is clearly calculated to signal jurisprudential stability around redistricting and the VRA. Khanna’s plan was a success. Rather than focusing on the current conditions of racial discrimination in voting, the Chief’s opinion is anchored in the history of the statute and the Court’s prior precedent. For the Chief, whether those precedents are correct seems beside the point.

For his part, Kavanaugh wrote a concurrence that explains his view that precedents involving long standing statutory interpretation deserve more deference than cases that involve constitutional interpretation. He does not mention Roe v. Wade (1973) or Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health (2022), but the implication is clear.

Khanna’s approach allowed the two conservative justices to uphold the lower court’s decision without addressing the complex issues of race in districting or having to endorse protections for minority voting rights. Paradoxically, while the opinion is bereft of soaring prose about the importance of voting rights or the need to correct historical wrongs, it is a landmark victory for minority voting rights.

The narrowness of the opinion will have two immediate benefits for minority voters: other pending Section 2 redistricting cases will be easier to win and Republican states redrawing their maps will have to be more cautious. By reaffirming 40 years of precedent, the Court signaled to lower courts to take Section 2 claims seriously. The Court also obliterated any hope that Republican legislatures may have to end run a weakened Section 2 in practical application.

This will likely also have major political consequences.

At minimum, Alabama will have to create a second Black-opportunity district for 2024.

So will Louisiana. Like Alabama, in 2021, Louisiana created a single Black-opportunity district, despite Black residents making up 33% of Louisiana’s population. And, like Alabama, Louisiana faced litigation, lost and appealed to the Supreme Court. Alabama’s defeat almost certainly spells the end of the road for Louisiana’s appeal.

Georgia will also likely be forced to create an additional Black-opportunity district in time for 2024. Like the other two states, Georgia was sued in 2021 for violating Section 2. In 2022, the district court in that case refrained from ordering a new Black-opportunity district due to the proximity to the 2022 midterm elections. With that election completed, the Georgia court has been barreling towards a final decision. The Supreme Court’s decision will almost certainly dictate that Georgia will lose, and soon.

Those three states — Alabama, Louisiana, and Georgia — will mean three new Black-opportunity districts and, if history is a guide, a net gain of three new seats for Democrats. Unsurprisingly, Khanna is the lead counsel in each of those cases as well.

Then there is Texas. There are several VRA lawsuits already pending in Texas federal court, including the one being led by Khanna. At stake are between two and five new minority-opportunity districts. With Allen now decided, expect the pace of the Texas litigation to pick up in advance of 2024.

There are other states where the Allen decision could reverberate in 2024. Voting rights litigators will undoubtedly take a second look at Florida’s congressional map. Tar Heel Republicans will have to avoid violating the VRA when they draw a new gerrymandered map for 2024. If not, they risk another humiliating defeat in court.

Shortly after I read the Court’s opinion, a reporter asked me what I thought it would mean for the fight for free and fair elections. Without thinking I said: “Today the Supreme Court did not break democracy.” That may not sound like much, but thanks to Abha Khanna and the other advocates in Allen, it is more than most expected. And most importantly, the Court’s decision is a win for voters that is worth celebrating.