Every Vote Counts Unless the GOP Doesn’t Like It

The GOP is determined to undermine democracy. This election shows how.

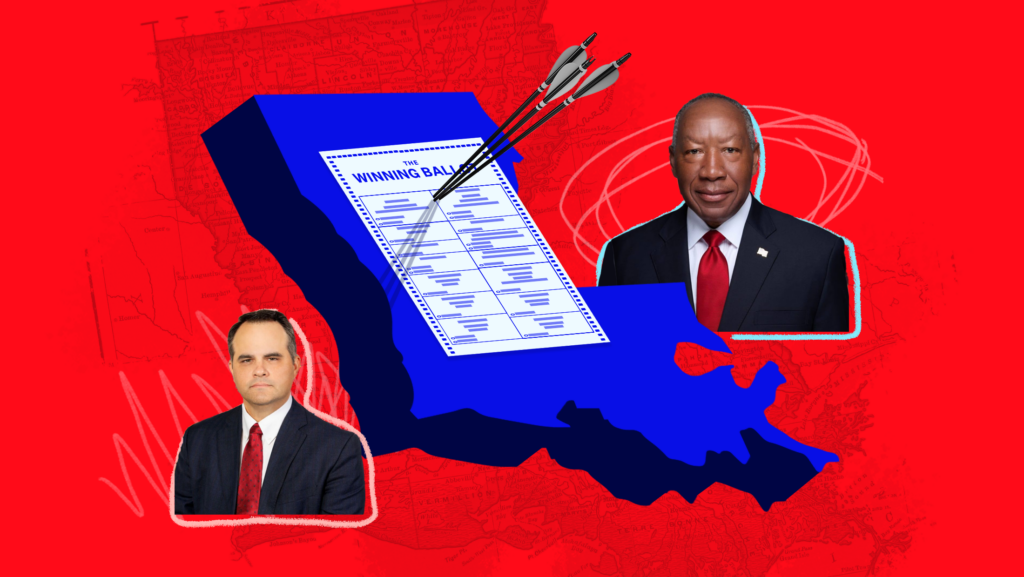

This past November, in an under-the-radar victory, the people of Caddo Parish, Louisiana, which contains the city of Shreveport, elected its first Black sheriff in the parish’s 185-year history. Henry Whitehorn, running as a Democrat, won by one vote, beating out John Nickelson, the Republican candidate endorsed by the outgoing sheriff Steve Prator, both of whom are white.

One vote. That’s how democracy works, right? Every vote counts.

Well, not for the people of Caddo Parish.

As in all close elections, the one-vote difference triggered a recount, which affirmed Whitehorn’s victory. But then the loser brought a lawsuit alleging various election irregularities and calling for a new election. According to Nickelson’s petition, there were two people who voted twice in the election; he also argued that some ineligible voters may have had their votes counted.

However, despite all of Nickelson’s suspicions about illicitly cast votes, he did not object on Election Day; instead, he waited for the final count and the recount before arguing that the election was unfairly tainted against him.

To be clear, there is no evidence that the alleged irregularities would have resolved in Nickelson’s favor. The two double voters were registered Republicans with leadership positions in the local party.

Nevertheless, Nickelson won in the courts, with a ruling narrowly affirmed by Louisiana’s Second Circuit Court of Appeal by a vote of 3-2. The state Supreme Court refused to hear Whitehorn’s final appeal.

Now, the voters of Caddo Parish must vote again for their sheriff, with a new election scheduled for March 23, the same date as the Republican presidential primary.

While this case could be chalked up to an unusual situation — winning by one vote is now rare — the proper way to see this case is as part of a concerted strategy by the GOP to use all available means at their disposal to remain in power. In the run-up to the 2024 presidential election, many experts have expressed concerns about the impact of extrajudicial violence and disinformation on the election outcome.

Without negating those concerns, those of us concerned about free and fair elections should also be worried about how those in power use laws, courts and policing to keep themselves in power.

Looking at the positions of the two candidates themselves is instructive. Whitehorn campaigned as a seasoned law enforcement officer with four decades of experience. He sought to improve relationships between police and the community by, for example, eliminating the use of stop-and-frisk as a policing tactic.

Anti-democracy and racism in this country are inextricably tied together. Access to the ballot box is a challenge to white supremacy.

Nickelson took the opposite view on stop-and-frisk. He has never served in law enforcement although the previous sheriff endorsed him for the position anyway.

Louisiana, like the rest of this country, has a wildly disproportionate number of white sheriffs. Over 90% of all elected sheriffs are white men. Caddo is a microcosm of the ongoing segregation in the criminal legal system. The parish is 50% Black, yet their sheriffs have always been white. The first Black prosecutor was just elected in Caddo in 2015.

Caddo Parish was, for a long time, also home to a disproportionate number of death penalty verdicts, especially of Black men. At its height, Caddo Parish sentenced eight times as many people to death as other states using the death penalty. Multiple high-profile exonerations — like those of Glenn Ford and Rodricus Crawford, both of whom are Black — also came from Caddo. This, plus ample reporting that showed race-based prosecutions and decisions in jury selection, suggest that, perhaps, the tough-on-crime attitudes of the elected law enforcement officials in this parish were detrimental to half of the community.

The intersection of racist policing and voting is not unique to Louisiana. The United States has a shameful history of denying Black voters access to the ballot box. After President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), multiple Black candidates ran for sheriff, in addition to other political positions locally. Some of them won. (The modern method to restrict Black voters’ access to the ballot box is now felony disenfranchisement. In Mississippi today, 16% of Black adults are ineligible to vote for the rest of their lives.)

White segregationists did their best to prevent Black candidates from winning office. They played on racist fears that Black voters would seek vengeance on white constituents for their cooperation in anti-Black policies and violence. Of course, this was entirely untrue, but the depth of white anxieties cannot be underestimated, especially when it came to the role of sheriff, which had both political sway and the firepower to back up their policies. The New York Times reported on this phenomenon in 1964, citing the fears of local whites that Black voters would “outvote” them. Instead, the reporter found, Black voters were “attempting to use their new power for the general welfare” and “improv[ing] race relations by eliminating extremists from office.”

One of those segregationists was the infamous Sheriff Jim Clark, who, in 1966, faced an opponent in the Democratic primary for sheriff. (His opponent Wilson Baker still declared himself a “segregationist,” but was less hostile to Black community members than Clark. The bar was pretty low.) When Clark didn’t win, he challenged six ballot boxes from primarily minority precincts, claiming that there had been voter fraud. The votes were almost all for Baker. A court forced Clark to count the ballots.

Clark, undeterred, ran as a write-in candidate, handing out pre-printed stickers with his name on it. All these efforts failed, but they failed because of grassroots organizing and the Voting Rights Act, which continues to protect Black and brown voters from discriminatory maps and voting rules. These protections, however, are not guaranteed to last since the U.S. Supreme Court already gutted a key provision of the VRA and right-wing forces keep trying to whittle the rest of it away.

Anti-democracy and racism in this country are inextricably tied together. Access to the ballot box is a challenge to white supremacy. Caddo Parish, Louisiana shows that Americans don’t need to wait for increased bouts of disinformation or the presence of armed militias at ballot boxes. Voter suppression is already happening, aided and abetted by local GOP parties, state and county officials and the courts.

Jessica Pishko is an independent journalist and lawyer who focuses on how the criminal justice system and law enforcement intersects with political power. As a contributor to Democracy Docket, Pishko writes about the criminalization of elections and how sheriffs in particular have become a growing threat to democracy.