Proportional Representation: Reimagining American Elections to Combat Gerrymandering

One aspect of American politics that’s been getting a lot of attention this year is redistricting and the way politicians can use redistricting to gerrymander congressional and legislative districts in their favor. One potential solution to gerrymandering, redistricting commissions, has been in the public eye with new commissions at work this year in Colorado and Michigan. But there are other, more radical ways to address gerrymandering. One such reform is switching our system of elections to a proportional system where the number of seats a party wins is proportional to its share of the vote.

Most elections in America use a plurality voting system.

In the United States, we elect most of our legislators at both the federal and state level through a plurality, winner-take-all voting system from single-member districts. In practice, this means that the one candidate who wins the most votes — not necessarily a majority — is elected. Some states, like Georgia, have runoff elections for certain positions, and in 2018 Maine became the first state to implement ranked-choice voting for federal offices. Additionally, a few states like Maryland elect legislators from multimember districts, though these states still use a plurality system, so the candidates with the most votes win (usually, this means one party just sweeps all the seats in a district). But for the most part, to win an election in the United States, you just need to receive the most votes to be elected.

This method of electing representatives has a variety of consequences. First and foremost, it means many politicians are elected without winning a majority of the vote. Rep. Angie Craig (D-Minn.), for example, won her election in 2020 with 48% of the vote. Our system also results in a large amount of “wasted” votes. In winner-take-all elections like ours, every vote cast for a losing candidate and every vote cast for a winning candidate in excess of the number required to win is wasted because those votes don’t impact the outcome of the election. Democratic votes in very red districts, for example, are wasted. At the same time, all the Republican votes in those districts in excess of the margin needed to win are also wasted. Finally, single-member districts are susceptible to gerrymandering. When a state has to be carved up into many districts that elect just one candidate, it’s easy to manipulate district boundaries and group different partisans together to determine election outcomes in advance.

All three of these factors combined can result in fairly unrepresentative election results. In 2012, Republicans won only 47% of the vote for the U.S. House but came out with 53% of seats. This disparity is even more apparent when you consider state-level results. In North Carolina, Democrats won 51% of the vote for the U.S. House but only 30% of seats. Likewise, Republicans won about 30% of the vote in Massachusetts but no seats in the U.S. House. Americans are consistently not getting the representation they vote for as our electoral system fails to fully account for the diversity of the electorate.

Proportional representation is an alternative voting system used in many other countries.

The U.S. is by no means alone in using plurality voting in single-member districts to elect legislators — Canada and the U.K. both elect their parliaments in this way, although plenty of their citizens wish they didn’t. But most other advanced democracies utilize another kind of electoral system to elect legislators: proportional representation.

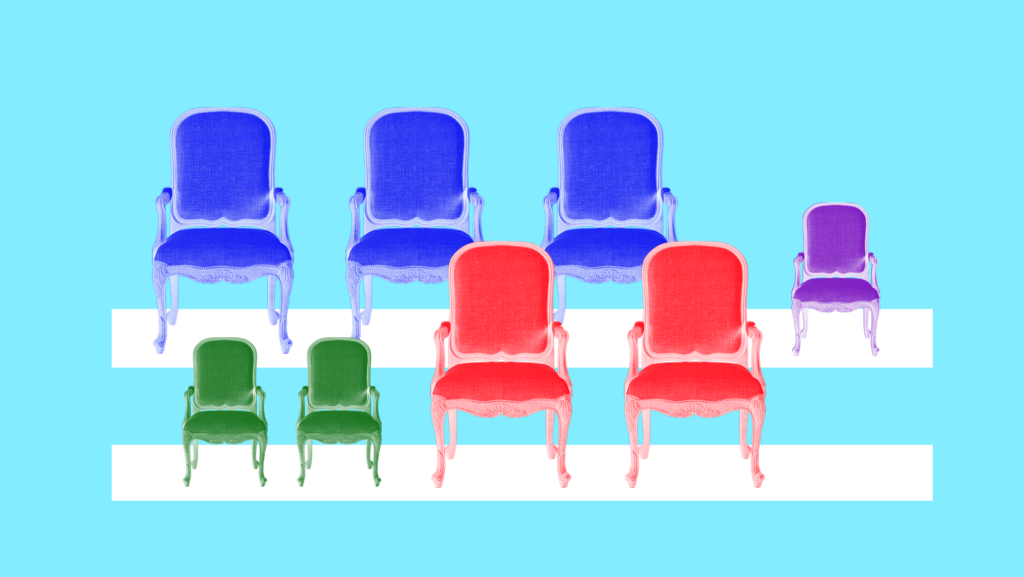

Broadly speaking, proportional representation aims to ensure political representation in the legislature — either on the national or state level — matches the voting preferences of the electorate. The actual mechanism for how this is achieved differs depending on the specific system chosen but typically involves using multimember districts rather than single-member districts. The key difference between a proportional system and a plurality system is that the seats in each district are awarded to multiple political parties based on their percentage of the vote, rather than simply having the most-voted party win all the seats — the election is no longer winner-take-all. For example, if in a five-member district, Party A wins 40% of the vote, Party B wins 40% of the vote and Party C wins 20% of the vote, then Parties A and B would both win two seats and Party C would win one. Once the results from all districts are aggregated, the partisan breakdown of the legislature roughly corresponds to the proportion of votes each party receives from the broader electorate.

One example of a country that uses proportional representation is Germany. In the 2021 Bundestag election, the three largest parties respectively won 26%, 24% and 15% of the vote. This corresponded to 28%, 27% and 16% of seats — much more in line with how the population voted than our election results often are.

Proportional representation has several key advantages over our current electoral system.

1. It limits gerrymandering.

One of the biggest advantages of proportional representation over our system is that it effectively renders gerrymandering impossible. On a basic level, multimember districts are simply harder to gerrymander. Multimember districts are larger, meaning there are fewer district boundaries to manipulate. This makes it more difficult for mapmakers to precisely slice up clusters of voters. More importantly, gerrymandering becomes much less effective since the political minority will always win political representation that matches its share of the vote no matter how the district lines are drawn. Drawing a multimember district where Republicans outnumber Democrats doesn’t preclude Democrats from still electing some representatives from that district.

2. It better represents the preferences of voters by ensuring fewer votes are wasted.

Proportional systems also tend to better represent voters by ensuring fewer votes are wasted. In a proportional election, every vote matters since each vote goes into determining how the seats are distributed to political parties. Even if your preferred party doesn’t win the most votes in your district, your vote still helps determine what share of the seats your party does win. Your preferences still end up being represented even if you don’t form part of a majority in an area. This would mean better representation for Americans throughout the country — Republicans in Massachusetts would likely win representation they currently lack in Congress, as would Democrats living in parts of the country that skew heavily Republican. The U.S. House of Representatives would align more closely with what voters actually want.

3. It encourages the development of third parties.

Finally, proportional representation tends to make third parties more competitive due to the lack of wasted votes. Our winner-take-all system encourages voters to either vote for the Democratic or the Republican candidate since those are the candidates most likely to win — voting for a third party almost guarantees your vote will be wasted. Under a proportional system, however, voting for a third party is more impactful because a third-party candidate doesn’t need to win the most votes to be elected. In a hypothetical five-member district, winning just 20% is enough to be elected. Given that many Americans wish they could vote for a third party, this might be one of the most compelling reasons to switch to a proportional system for our elections.

Proportional representation is becoming increasingly popular.

While much of the focus on electoral reform in our country has been directed to things like redistricting commissions or bans on partisan gerrymandering, proportional representation is growing in popularity among advocates. The organization FairVote is pushing for legislation to implement a proportional system for elections to Congress — H.R. 3863, the Fair Representation Act — and there’s a growing consensus among political scientists that proportional representation is the best way to improve our system of government. Advocates also argue proportional representation would boost turnout and might even address extreme polarization.

Switching to a system of proportional representation would represent a huge change in how we elect our representatives. But as we highlighted in our Data Dive last week, Americans are highly dissatisfied with our political system and are near-unanimous in wanting significant changes. Given the desire for change and the failure of redistricting commissions to fully solve our gerrymandering problem, there may be no better time to consider more radical solutions than now.