Civil Rights Groups Poised to Take Texas’ Voter Suppression Law to Supreme Court

Voting advocates are signaling that they may soon ask the U.S. Supreme Court to review their long-running challenge to Texas’s sweeping voter-suppression law, S.B. 1, under Section 208 of the Voting Rights Act.

Should the justices hear the case, it could let the court’s conservative majority issue a ruling that makes it even harder to challenge restrictive voting laws going forward.

Get updates straight to your inbox — for free

Join 350,000 readers who rely on our daily and weekly newsletters for the latest in voting, elections and democracy.

Civil rights and pro-voting organizations last month requested additional time from the Supreme Court to file a petition for review. Last week, Justice Samuel Alito granted an extension until Dec. 27 – a strong indication that an appeal is under serious consideration.

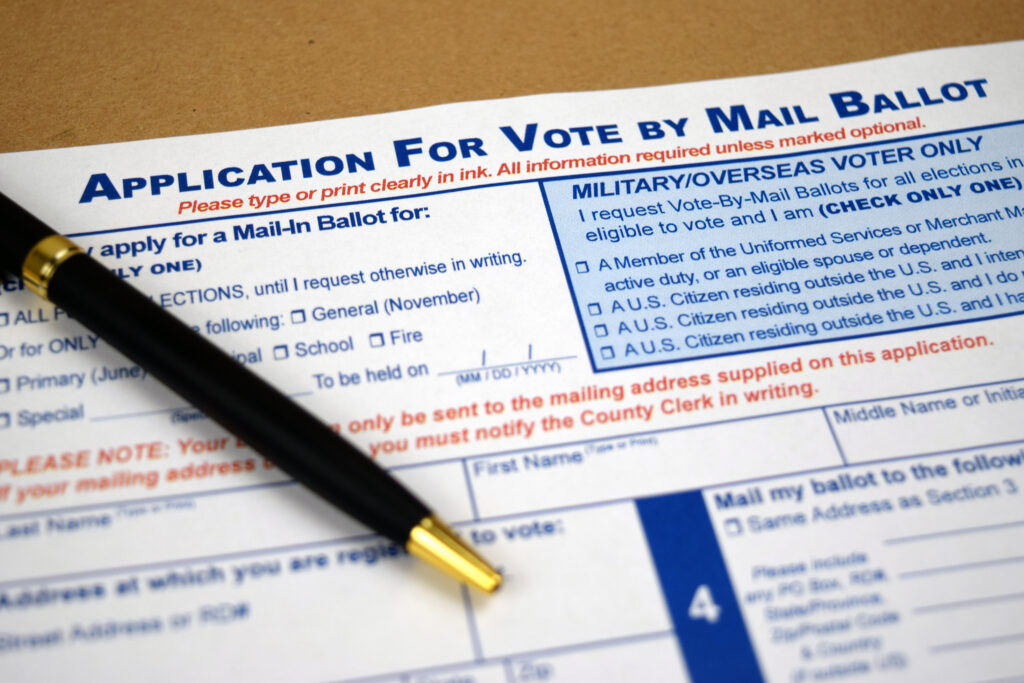

If they move forward, the plaintiffs will ask the justices to review an August appeals court ruling that upheld several key provisions of Texas’ restrictive, multi-pronged law, including bans on paid assistance with mail-in ballots, a felony prohibition on paid canvassers interacting with voters in the presence of a mail-in ballot, new disclosure requirements for voter assistors, and an expanded oath taken under penalty of perjury.

The claims are part of a broader set of six consolidated lawsuits targeting different aspects of the law.

The request comes as legal battles over S.B.1 continue to unfold in the 5th Circuit. On Tuesday, a three-judge panel – two appointees of President Donald Trump and one of President Ronald Reagan – heard oral arguments in Texas’ separate appeal over S.B. 1’s “vote harvesting” provision.

That provision makes it a felony – punishable by up to ten years’ imprisonment – for paid canvassers to interact with voters in the presence of a mail-in ballot. It was struck down by a district court last year.

The plaintiffs argued that the provision is an unprecedented infringement on free speech and voter outreach in violation of the U.S. Constitution.

“Mail-in voting has been around since the Civil War. All 50 states, your honor, allow mail-in ballots,” their attorney argued. “No other state has ever had a law like this that makes it a crime for paid political canvassers to go door to door and talk to somebody in the presence of a ballot. This is an extraordinary break from our constitutional tradition.”

Lawyers for Texas defended the provision as a narrow attempt to prevent coercion of mail voters. Republicans echoed the state’s concerns, stressing that mail-in voting involves “vulnerable populations” and occurs outside the oversight of election workers. They argued that protections against pressure and coercion are “even more vital for mail ballots than they are for in-person ballots.”

Several comments from the bench suggested the panel may be inclined to reverse the lower court’s order blocking the provision. At one point, Judge Edith Jones, the Reagan appointee, presented a scenario involving a paid canvasser aggressively berating a voter about their political choices.

Jones described such conduct as “right in the heartland of what the statute is intended to prevent.”