What Happened to Florida’s 5th Congressional District?

In March of 2022, the Florida Legislature approved a new congressional redistricting plan, proposing a primary and secondary map that would redraw Florida’s congressional districts. The primary map, which was lauded by Republicans in the Legislature, would further gerrymander the state towards Republicans in large part by gutting the power of Black voters in Florida.

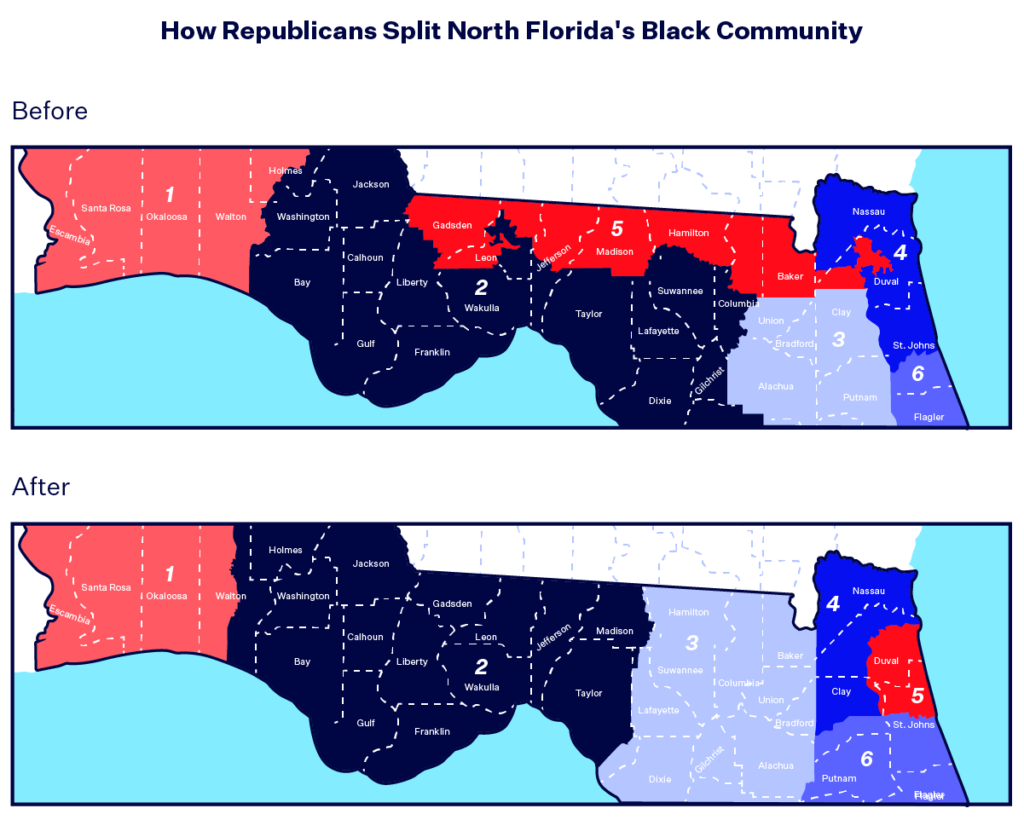

Foremost, the plan would dismantle Florida’s 5th Congressional District, a heavily Black district that features the city of Jacksonville and is home to the largest Black population in the state. The Black voter population would go from 45% to 34%, with Jacksonville being cracked into two districts. What followed was a contentious and complicated fight between Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) and his usual allies in the Legislature. DeSantis, remarkably, felt the maps did not go far enough, and vetoed the proposal.

The governor subsequently called a special session to draw a new map, which likewise dismantled the 5th Congressional District and additionally targeted the 10th Congressional District that is also home to a wide swath of Black voters. DeSantis’ new congressional map specifically cracked Black voters who originally resided with the 5th Congressional District across four separate districts, thereby denying them of the opportunity to elect their preferred candidate in northern Florida.

With Black Floridians making up 17% of the state’s population, this move was a blatant attack on Black voting power, and prompted Democrats in the Legislature to stage a sit-in to protest the proposed map. In the face of inspired comments from those like Florida House Rep. Travaris McCurdy (D-Orlando), who said, “[w]e shouldn’t be asking for representation in 2022…I’ve had enough of being kicked about in this chamber and still be expected to smile and shake hands with the people that are trying to oppress my people,” the Florida Legislature pushed the map through in just three days on a party-line vote and DeSantis signed it the next day.

Since the signing of the new map, two lawsuits have been filed, and movement in the cases has been frequent. Just this week, parties in the state-level lawsuit agreed to narrow the focus of the claims, a move that pro-voting groups argue increases the likelihood that North Florida regains a Black-performing district.

The northern Florida district, home to Jacksonville and Tallahassee, has had a long history of Black representation.

Following the 1990 census, the Florida Legislature created a new map that would feature a majority-Black district, the 3rd Congressional District. This district paved the way for Florida voters to elect a Black representative to Congress for the first time since Reconstruction. The large Black population throughout the rural counties represented by the district, such as Gadsden County, the only majority-Black county in the entire state, is a result of slavery as the largest concentration of plantations in Florida was in this region.

In 1992, Corrine Brown was elected to this new seat, which she held until 2013, when her district was renumbered as the 5th Congressional District. The geography of the district stayed mostly intact and Brown held the seat for four more years until she lost the Democratic primary to former Rep. Al Lawson (D-Fla.) in 2017. Lawson went on to win the seat in the general election, continuing the decades-long history of Black representation in the Jacksonville-based district. Lawson represented the 5th Congressional District seat until this past election cycle, when Florida Republicans redrew the map and eliminated his majority-Black district. Despite this redraw, Lawson still ran for re-election in what is now the 2nd Congressional District during the 2022 midterm elections, and ultimately lost to a white Republican.

The 5th Congressional District had, for years, been appreciated as a way for Black voters in northern Florida to have important representation in Congress. Black voters took advantage of the opportunity, electing representatives who were reflective of their communities for three straight decades.

In 2015, the Florida Supreme Court reiterated the need for fair representation, ordering a redraw of the map that would preserve Black representation. Kiara Smith, a Black businesswoman and one of Lawson’s constituents at the time, described the value of the historically majority-Black district, saying “[t]he best representation is someone who knows what it’s actually like to be a Black person in America, and that’s going to be another Black person.” With Lawson out of office due to the dismantling of the 5th Congressional District, Smith is no longer able to elect her preferred candidate.

Ongoing lawsuits could bring much-needed Black representation to northern Florida.

Within hours of DeSantis signing the new congressional map in April 2022, pro-voting groups filed a lawsuit in state court challenging the constitutionality of the new districts. The state court lawsuit alleges that the map diminishes the ability of Black voters in Florida to elect their candidate of choice, particularly in the 5th Congressional District, and that the map violates the Fair Districts Amendment of the Florida Constitution. The lawsuit also argued that the map was a partisan gerrymander that favored Republicans, but those claims have since been dropped by the plaintiffs.

Another lawsuit filed in federal court, which originally argued that Florida lawmakers would not be able to produce a congressional map in time and therefore needed a court to redraw, was later amended to argue that the new map intentionally dilutes Black voting power in violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. In both the state and federal cases, the plaintiffs are seeking for the respective courts to strike down the congressional map and order the creation of a new map that would comply with the Fair Districts Amendment and/or the U.S. Constitution. A new map would pave the way for more Black representation in Florida’s congressional delegation by restoring the Sunshine State’s 5th Congressional District.

The state-level case has taken a winding and convoluted path through multiple court levels. In May 2022, a trial court judge temporarily blocked the map, agreeing with the plaintiffs that it violated the Fair Districts Amendment “because it diminishes African Americans’ ability to elect candidates of their choice” in northern Florida. However after multiple rounds of appeals — including an appeal by the Florida Secretary of state to a state appellate court and an appeal by the plaintiffs to the Florida Supreme Court — the DeSantis map ultimately remained in place for the 2022 midterm elections and is still currently in place.

Then, in a surprising but welcomed twist earlier this week, the parties in the lawsuit reached an agreement that seemed to increase the likelihood that a Black-opportunity district could soon return to North Florida. The agreement limits the scope of the lawsuit to just North Florida, meaning that all claims pertaining to other districts in Florida will be dropped. The plaintiffs also agreed to dismiss their claims concerning partisan gerrymandering. Now, the only legal question outstanding is whether or not the “non-diminishment” provision of the Florida Constitution violates the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

As a result of the stipulation, which pro-voting groups hailed as a promising step forward for Black voters, the court agreed to delay the original trial date of Aug. 21 and instead hold arguments on the aforementioned question on Aug. 24. Following arguments, it will be up to a Florida judge to decide whether or not the state’s current congressional map will be struck down.

In response to the agreement, Lawson said that he would be open to running for Congress in North Florida again if a new district is created that is similar to his old district.

Meanwhile, the lawsuit in federal court has been more straightforward. The defendants in the case filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, which was largely denied in November of last year. While the court dismissed DeSantis as a defendant, it allowed claims against the Florida secretary of state to proceed. The Florida secretary of state has since filed a motion for partial summary judgment, which the judge has yet to act upon. Trial in the case is scheduled to begin on Sept. 26.

As the Florida Legislature, with DeSantis’ support, tried to push through unfair maps at the beginning of 2022, Lawson told a local news outlet that it was “evident that DeSantis is trying to restrict minority representation, specifically African American voters,” and that he was “confident that this attempt by the Governor to dilute the voting rights of my constituents is in clear violation of the Voting Rights Act and the Constitution.” With the governor now having done the former, it will be up to the courts to decide whether the latter is indeed so.