What Can We Learn From the History of Felony Disenfranchisement?

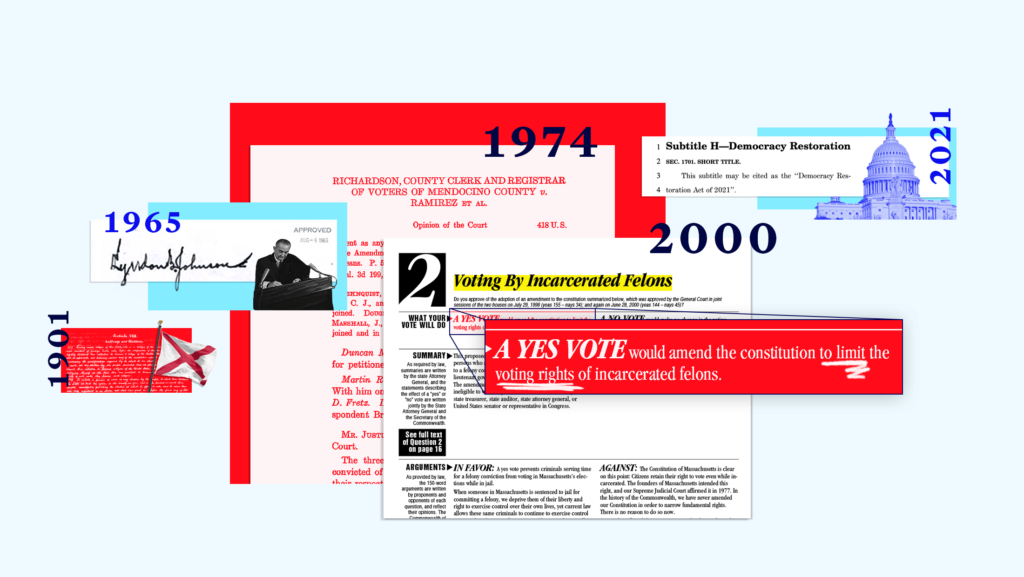

In 1997, a handful of incarcerated men in Massachusetts decided to form a political action committee mainly focused on voter registration and education of both incarcerated people and their families. This action was quickly hampered by an opposition movement determined to revoke the right to vote while incarcerated — then-acting Gov. Paul Cellucci (R) proposed a ballot initiative to do just that, which passed overwhelmingly in 2000.

Today, in 48 states people incarcerated for a felony conviction cannot vote. Felony disenfranchisement is defined as the loss of voting rights on the basis of a felony conviction — whether that loss only applies during the time of incarceration or for differing periods after a prison sentence is completed varies from state to state. We covered the basics of these laws and their current status across the country last week in “Felony Disenfranchisement Explained,” but now we ask, how have felony disenfranchisement laws changed over the years? Are the voting laws we know today really the status quo? In today’s piece, we look at the history of felony disenfranchisement laws, how they have developed over the past few decades and the legal environment surrounding them to get a better understanding of the path forward for reform.

Before 1900: The racist origins of felony disenfranchisement

The idea of “civil death” — losing certain civic and public rights as a punishment for a crime — can be traced back to ancient Greece and Rome and were later transformed into the English laws that were brought to the British colonies. Although some state constitutions established a version of criminal disenfranchisement in the early 1800s, most of the modern felony disenfranchisement laws that we know today originated after the Civil War.

When Black men were granted the right to vote in 1870, Southern states started to adopt felony disenfranchisement laws, not long before they adopted poll taxes, literacy tests and grandfather clauses, all tools designed to prevent Black voters from accessing the ballot. These disenfranchising laws went hand in hand with extralegal efforts — terrorism and direct intimidation — to maintain white supremacy. In fact, a 2003 study found that the larger a state’s nonwhite prison population, the more likely they were to adopt the strictest of felony disenfranchisement laws.

This racial intent was in plain sight in most states. In Alabama, the 1901 Constitution revoked the right to vote from people who committed a “crime involving moral turpitude” (meaning behavior that’s contrary to “good morals”), a phrase that was left purposefully vague to ensure that Black voters could be selectively disenfranchised (the term was only defined in 2017).

1950s-1990s: When laws changed, but legal challenges failed

Of the 48 states that would eventually have a felony disenfranchisement law, 42 states adopted their first law by 1912. However, it wasn’t until the second half of the 20th century that the trend reversed — in the 1960s and 1970s, there were upwards of 20 changes that liberalized state laws to different extents, mainly in restoring voting rights to people who have completed their sentences. And with the passage of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965, Congress added new protections to ensure equal access to the ballot box and legal avenues to challenge potentially discriminatory laws.

The U.S. Supreme Court first weighed in on felony disenfranchisement in Richardson v. Ramirez (1974). Three individuals with prior felony convictions who had finished their sentences were not allowed to register to vote, so they challenged the provisions of the California Constitution and related statutes that disenfranchised them under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The Equal Protection Clause states that “no state shall… deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The California Supreme Court held that the disenfranchisement provisions violated the Equal Protection Clause, which the Supreme Court then reversed. To support its decision, the Supreme Court pointed to Section 2 of the 14th Amendment which forbids the abridgement of voting rights “except for participation in rebellion, or other crime.”

The Richardson decision all but closed the door to challenging the overarching concept of felony disenfranchisement laws as unconstitutional but left open the possibility for certain laws to be challenged on the basis of unequal enforcement or racially discriminatory intent. The Supreme Court weighed in one final time on an Equal Protection challenge in Hunter v. Underwood (1985), finding Alabama’s 1901 “moral turpitude” provision unconstitutional because both discriminatory impact and discriminatory intent were present.

With the Equal Protection question fairly resolved, advocates began to challenge felony disenfranchisement under Section 2 of the VRA, specifically in cases such as Wesley v. Collins (1985), Baker v. Pataki (1996) and Farrakhan v. Locke (1997). Since federal appellate courts have decided cases raising Section 2 claims differently, but the Supreme Court didn’t take up these cases, the legal theory around Section 2 challenges to felony disenfranchisement is far less settled.

1990s-2020: A positive trend toward reform

While six states passed restrictive felony disenfranchisement laws amid the “tough on crime” rhetoric of the 1990s, the overall trend of improving voting access for incarcerated people has accelerated in recent years. Since 1997, 25 states and Washington, D.C. have expanded eligibility, streamlined the restoration process or improved voter education. This includes 10 states that have repealed or amended their lifetime ban on former felons voting.

In 2020, the Black Lives Matter movement renewed focus on the United States’ criminal-legal system and its disproportionate impact on people of color. The public pressure succeeded in pushing Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds (R) to sign an executive order automatically restoring the right to vote for people with past felony convictions, excluding homicide offenses, once they complete their sentence. Iowa had previously remained the last and only state that permanently disenfranchised all people with past felony convictions. The same summer, the Washington D.C. city council passed a police reform bill with a provision extending the right to vote to any resident imprisoned for a felony conviction, making Washington D.C. the first to proactively restore voting rights for those currently serving time in prison.

What’s next for voting rights restoration?

Given this recent momentum across the states, now’s the time to keep pushing for change. As the path to overturn felony disenfranchisement laws in court remains unclear, reform to felony disenfranchisement will likely occur through legislative means.

Here’s what we can do:

First, Congress must pass The Freedom to Vote Act, S. 2747, an expansive voting rights bill that establishes national standards for elections and ballot access. The Act includes a provision known as The Democracy Restoration Act, which would ensure that everyone who has completed their prison sentence and is now back living within their communities has the right to vote. In other words, if passed, the right to vote could not be abridged on the basis of a criminal conviction unless the “individual is serving a felony sentence in a correctional institution or facility at the time of the election.” While the Freedom to Vote Act failed to overcome a Republican filibuster a few weeks ago, the legislation is still awaiting future action. S. 2747 is crucial because it would restore the right to vote to millions of citizens who have completed their prison sentences, and if passed, would simplify the patchwork of laws across the country.

Second, in the absence of federal action, states can still take proactive steps towards voting rights restoration, and even go beyond the minimum standard proposed in the Freedom to Vote Act. Voters can, and should, lobby state legislatures to introduce and pass legislation, as states have been seriously considering proposals for reform (or abolishment of felony disenfranchisement altogether by allowing everyone in prison to vote, as they do in Maine, Vermont and Washington, D.C.) in recent years. Another possible route to change is through a citizen-led ballot initiative in the 26 states that permit them, 18 of which allow constitutional amendments.

By looking into the history of felony disenfranchisement, we get a better sense of both where we came from and where we’re headed. The election and voting rules that we know today haven’t always been the status quo, and that means they don’t have to remain static either — we should be open to reforming and improving them.