To Understand Redistricting, First Look At Who Holds The Power

With the release of census data in August, the once-in-a-decade redistricting process is well underway. In redistricting, whoever initially controls the drawing of new congressional and state legislative districts has the most influence in the final outcome of a redistricting plan — including whether new maps will be fair or discriminatory. The U.S. Constitution largely leaves control of redistricting up to the states and historically it has been up to the politicians in power in each state to decide how new districts will look.

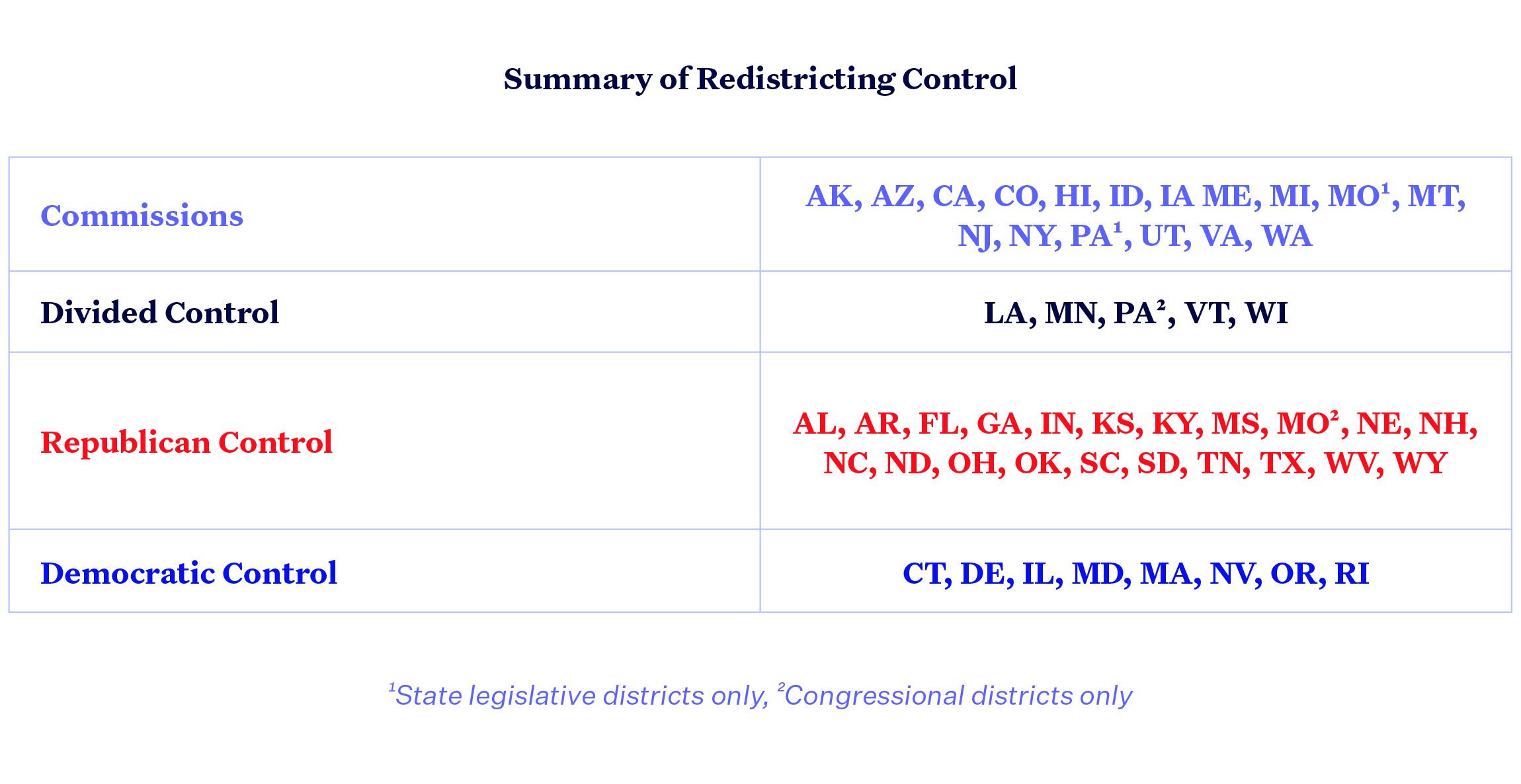

But understanding who controls redistricting in a state isn’t as simple as looking at which party is in control of the state’s government. While the majority of states still leave it up to the politicians to draw new district lines, others have independent commissions that are fully responsible for redistricting or advisory commissions that have the first opportunity to draw maps. Even in states where politicians still control the process, things aren’t always so clear-cut. In North Carolina, for example, although the governor is a Democrat and the General Assembly is controlled by Republicans, Republicans actually retain full control of the redistricting process because only the state Legislature has a hand in drawing new maps. Similarly, in Massachusetts, although the governor is a Republican, the Democrats have a supermajority in the state Legislature and can override any veto of a favorable district plan.

As more and more states begin drawing new maps, today’s Data Dive takes a closer look at who is in charge of the redistricting process in each state. A report from New York University School of Law’s Brennan Center breaks this down, surveys how things have changed since the last redistricting cycle in 2011 and analyzes what this means in the fight for fair maps.

Here are the key takeaways:

An increased number of states will use commissions to draw new districts.

Since 2011, five states — Colorado, Michigan, New York, Utah and Virginia — have adopted reforms that will give commissions a greater hand in creating their redistricting plans. Colorado’s and Michigan’s reforms are especially robust, as mapmaking will be completely handed over to fully independent commissions. Michigan’s new commission will also have a chance to unwind some of the country’s most gerrymandered districts. These reforms bring the total of states using a commission for at least part of the redistricting process to 17.

Commissions tend to draw fairer maps by attempting to take political considerations out of the redistricting process. However, it’s important to understand that not all commissions are made equally. While the commissions in some states, like Arizona, retain complete authority over redistricting, those in other states like Maine only act in an advisory capacity. Additionally, while some commissions are truly nonpartisan, others are better characterized as bipartisan and are made up entirely of politicians. Still, even imperfect commissions tend to draw maps that are more responsive to voters and protect the interests of communities of color.

Republicans and Democrats will share control of redistricting in more states.

In addition to the increased number of states using commissions, more states will be drawing maps with control split between the parties due to political changes over the last decade. In particular, Democrats won important gubernatorial races in Louisiana, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin in 2018 and 2019. All three states were under full Republican control in 2011 and per the report drew heavily gerrymandered or racially discriminatory districts. Now, Democratic governors in each of these states will wield a veto over the most egregious plans put forward by Republican state legislators — and Republicans won’t be able to override a veto. In addition to these three states, Minnesota and Vermont will also draw new maps under divided control.

When control of the redistricting process is divided, fairer maps are more likely as each political party effectively wields a veto over the other’s proposals. Additionally, if the parties fail to compromise, map drawing tends to end up in the courts, which historically create districts that are not as excessively partisan as ones drawn by politicians.

However, the majority of states will still draw maps under full partisan control.

Although fewer states will draw maps under full partisan control due to the increase in commissions and instances of divided government, political parties still control the redistricting process in most states. As in 2011, Republicans will again have the upper hand, controlling legislative redistricting in 20 states and congressional redistricting in 21. These include crucial battleground states like Florida, Georgia, North Carolina and Texas. Democrats will only fully control the process in nine.

Fairer maps are more likely.

As the study notes, “the biggest predictor of whether a state will draw fair maps is whether a single party controls the map-drawing process.” Accordingly, both the increase in the use of commissions and more divided state governments will increase the prospects for fair maps across the country this redistricting cycle. However, since redistricting is still controlled by a single party in many states, we can expect partisan gerrymandering as well — especially in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina and Texas.

Redistricting, however, is a long and complicated process and there are bound to be many twists and turns along the way before new districts are in place. Some states that have only advisory commissions, like New York, may try to override or greatly amend the maps they draw. Other states with divided governments may opt for backroom deals that result in bad maps, as occurred in Virginia in 2011. Even when states approve new maps, litigation is almost assured. While redistricting begins with who draws the maps, it definitely doesn’t end there.