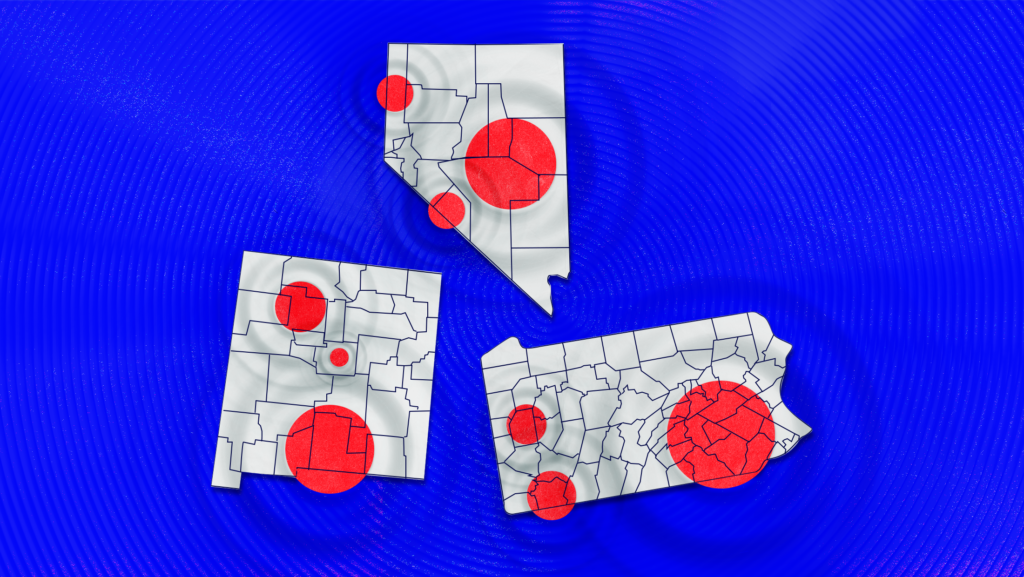

The Counties That Stalled Certification in the 2022 Primaries

From New Mexico to Pennsylvania, a handful of county boards illustrated during the 2022 primary elections what can happen when individuals tasked with ministerial roles intentionally derail the post-election process. After this year’s primaries, at least ten counties either refused to certify election results, certified incomplete results or prolonged and discredited the certification process. While these spats were ultimately resolved and didn’t impact the outcome of the respective races, they foreshadow a looming threat to American elections.

What happens between the time polls close on Election Day and official results are confirmed is a technical and overlooked process that varies from state to state. However, almost all states rely on a county-level body to count or canvass results and submit them to the secretary of state or state board of elections. A “canvass” includes the tabulating of ballots, double-checking total results and transmitting the outcome of that election from a local jurisdiction to the state. In the six New England states — Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont — canvassing takes place at the town, precinct or polling place level, before being sent directly to the state, instead of via a county board.

“The mechanics of vote counting rely on a convoluted series of decisions by individual officials,” wrote law professor Quinn Yeargain, introducing a database of the canvassing and certifying structures in each state. “Even when their tasks are ceremonial, the system may still hinge on their operating in good faith and without desire to overturn an election.”

The system almost faltered this spring when election officials from a handful of counties scattered across the country failed to complete their tasks. Democracy Docket has identified at least 10 counties where there were abnormalities in the election certification process — four in Pennsylvania, three in New Mexico and three in Nevada.

The most notable example emerged from a rural, solid red area in New Mexico. In Otero County, the three-member county commission unanimously voted against certifying the results of the June 7 primary election, citing unfounded claims about voting machines yet failing to identify any specific evidence. New Mexico Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver (D) quickly asked the courts to step in. Soon after, the New Mexico Supreme Court ordered the commission to comply with its statutory duty and certify the election results. “If you have questions, you have the opportunity to look into those,” Alex Curtas, director of communications for the New Mexico secretary of state, told Democracy Docket, describing the expectations of county commissioners. “But now it’s your duty to certify the election. And that’s, of course, what the Supreme Court agreed with us on.” The commission ultimately voted 2-1 to certify the results, with Commissioner Couy Griffin remaining the lone dissenter. (Griffin, the founder of Cowboys for Trump, was recently removed from office under the “insurrectionist” clause of the 14th Amendment for his involvement on Jan. 6, 2021.)

Something more subtle, but no less subversive, was happening across the country. Four Pennsylvania counties — Berks, Butler, Fayette and Lancaster — certified incomplete results from the May primary and purposefully excluded certain valid ballots from their totals. The state of Pennsylvania caught the issue and sued. A court ruled in August that the counties must include these ballots in their results. Following the court order — over three months after the primary election — the obstinate counties finally certified complete results. (A spokesperson for the Pennsylvania Department of State informed Democracy Docket that the department has issued updated guidance to counties to make it clear which ballots must be included come November, but reiterated that otherwise, May was “a successful primary election.”)

While Otero County, New Mexico and the handful of Pennsylvania counties captured the most attention, several other county-level commissions discredited the typically routine process:

- After initially delaying certification to hear the concerns of residents, the commissioners in Torrance County, New Mexico ultimately certified election results on the morning before the state-imposed deadline to do so. During the public meeting, angry citizens shouted “cowards,” “traitors” and “rubber stamp puppets” at the board members. Much of the ruckus was centered over misinformation about voting technology.

- In Esmeralda County, Nevada — a county with a population of less than 750 where former President Donald Trump received 82% of the vote in 2020 — the conspiracies pushed the county’s commissioners to conduct a hand count of the results. It took the commissioners over seven hours to hand count the 317 votes that were cast, ultimately being the last Nevada county to certify its results.

- A commissioner voted against certifying election results on the respective canvassing boards in Sandoval County in New Mexico and Nye and Washoe counties in Nevada. Luckily, these lone dissenters didn’t stop the boards from all certifying the results 4-1.

The actions of election administrators in this assortment of counties did not impact the ultimate outcome of any races, nor derail the process completely. But, it’s not hard to imagine the negative effect of a three-month delay and ongoing legal battle, like what took place after the Pennsylvania primaries, if that were to occur after a close presidential election. In fact, a single county — or in those New England states, a single precinct — can derail the certification process. States cannot certify their state-level results until all jurisdictions have certified and submitted results.

After the 2020 election, the Republicans on the elections board in Wayne County, Michigan — home to Detroit — refused to certify the presidential election results. The deadlock ended after immense public outcry, but this provided the basis for a GOP member on the Michigan Board of State Canvassers to consider voting against certifying the state’s presidential results, despite his role being a mere formality. This canvasser ultimately abstained and the other Republican canvasser chose to vote alongside the Democratic commissioners, so the results were certified and the crisis averted.

The crisis might not be averted in future elections. For example, the newest Wayne County canvasser has already said he would not have certified the 2020 election results. State officials are preparing now: “If canvassers refuse to certify, they will be doing so to spread misinformation and undermine the legitimacy of the election because the law is clear on their responsibility,” a spokesperson for the Michigan secretary of state explained. The department is also trying to preempt this issue by making sure that the public knows any attempts to refuse to certify results “will be futile, and that they should not be deceived by it.”

Alex Curtas, on behalf of the New Mexico secretary of state, said that New Mexico’s election code is already quite explicit about the ministerial duty of county election boards. Additionally, the law gives commissioners a certain amount of time to raise and investigate legitimate concerns. “I think that June was a good test of our laws and procedures,” Curtas added. “We are obviously going to be very vigilant for these kinds of attempts again after the November election, but I think that we have a good precedent from the [New Mexico] Supreme Court.”

Other states are looking to build this kind of language into state election code or constitutions. Michigan voters will consider a ballot initiative this November which, among other pro-voting provisions, outlines that the role of the Board of State Canvassers is “ministerial, clerical, nondiscretionary” and based solely on the counted votes. In May, the Colorado Legislature passed the Colorado Election Security Act, a priority piece of legislation for Secretary of State Jena Griswold (D), which gives authority to the Colorado secretary of state to certify county results if a majority of a county canvass board fails to do so by the applicable deadline.

There are over 10,000 election administration jurisdictions in the United States, ranging from small towns to large, metropolitan counties. Just a handful of election officials overturning the will of their residents or a scattering of counties or towns disregarding rule of law can have a profound ripple effect. The number of counties with election administrators who create serious issues in the certification process may climb from ten in the primaries to a much higher figure come November.