The U.S. Court System, Explained

In 2022, there will be no shortage of crucial cases on redistricting and voting laws in the U.S. court system. However, only the smallest fraction of those will ever make it to the U.S. Supreme Court. Instead, the vast majority of cases are decided in lower courts, both state and federal. In today’s Explainer, we cover the basics of the U.S. legal system, the structure of the courts and how a case may move through it.

The United States is a dual court system where state and federal matters are handled separately.

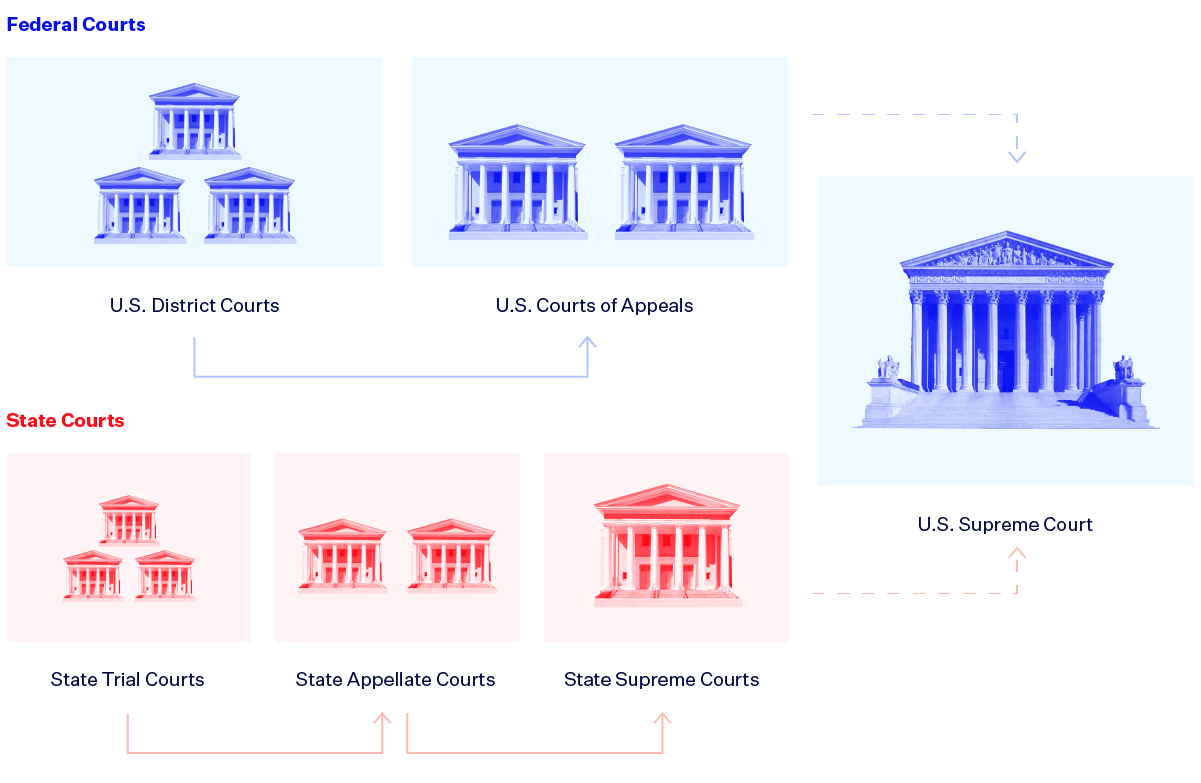

There are two types of courts in the United States — state and federal. You can think about them as parallel tracks that can (though rarely) end up in the U.S. Supreme Court. Within the two respective tracks, there are three main levels: trial courts, appellate courts and the highest court for that respective track.

First, it’s important to understand jurisdiction: a court’s authority to hear cases and make legal decisions. Jurisdiction refers not only to a court’s geographic scope, but also whether there is a federal or state question at hand.

- To file a lawsuit in federal court, one must allege that there is a breach of federal law or the U.S. Constitution — these are cases that raise a “federal question.” Federal courts also hear a unique type of case involving “diversity of citizenship” where the case is between citizens of different states and potential damages exceed $75,000.

- In contrast, state courts are known as courts of general jurisdiction, meaning that one can raise any claim under state or federal law, except those that are under exclusive jurisdiction of federal courts.

In either federal or state court, a case starts at the lowest level: a U.S. district court or a state trial court, respectively. If a party disagrees with the outcome at the trial level, they can appeal it to a higher court and eventually petition all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court.

There are, of course, exceptions to these procedural rules. Here are two notable ones:

- The U.S. Supreme Court has original jurisdiction — the authority to be the first court to hear a case — over specific matters, such as disputes between states. In such rare instances, the U.S. Supreme Court would be the first and only court to hear the case.

- After a three-judge panel decides a redistricting case alleging constitutional violations, that case will automatically jump from district court to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court is forced to hear it, as well as three other types of cases that have a mandatory right to be heard by the highest court in the country.

The federal court system:

The federal court system has three main levels: district courts, circuit courts and the U.S. Supreme Court. Federal judges and Supreme Court justices are appointed by the president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate for a lifetime term.

District courts are the starting points for federal cases and where a trial takes place.

There are 94 active district courts across the country. Each U.S. state has between one and four districts, and Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia both have one district court. Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands also have their own territorial courts that function as district courts.

The number of judges varies widely by district. The U.S. District Court for the Central District of California and the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York have 28 judges each, the highest in the country. In contrast, the U.S. District Court for the District of Idaho only has two judges, as do several other district courts. District judges can also appoint magistrate judges, judicial officers who serve time-limited terms and assist with proceedings, due to the heavy workload at the trial level.

Circuit courts are the first level of appeal.

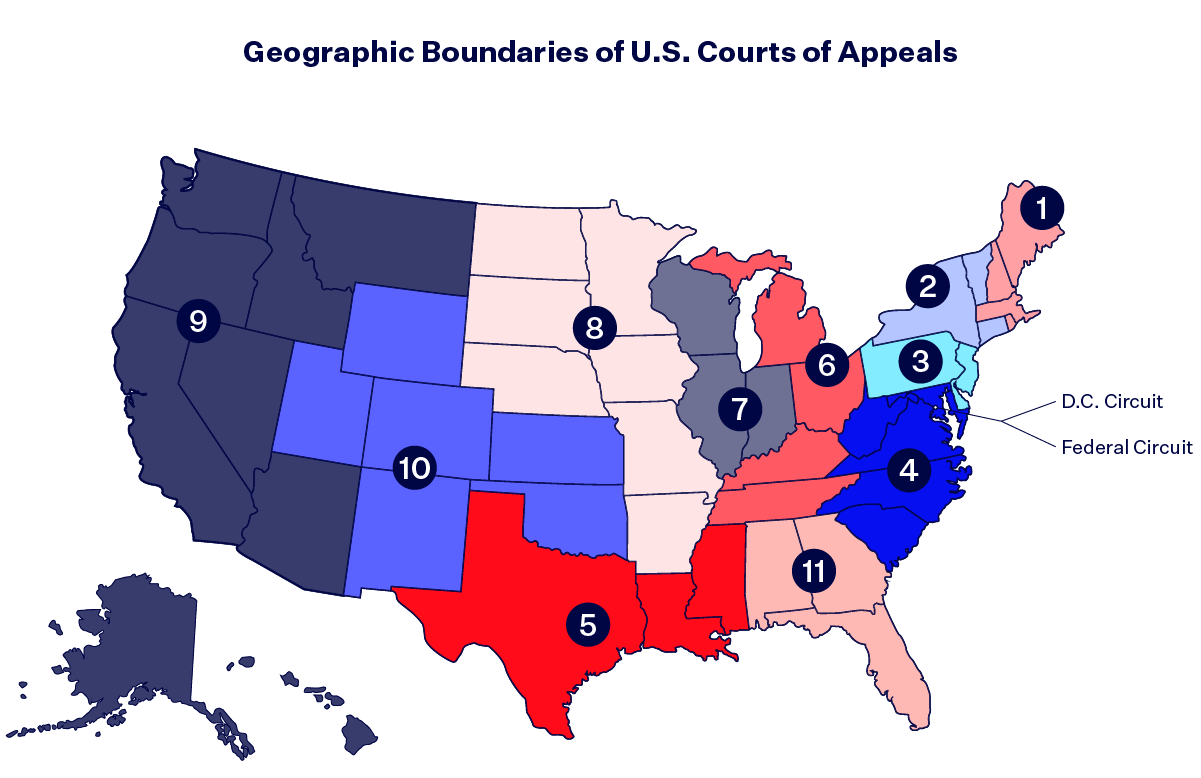

There are 13 circuit courts: 12 are organized geographically and one is the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which hears specific national jurisdiction cases including patent lawsuits and appeals from the U.S. Court of International Trade. For example, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals includes Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee, so any case decided within the nine districts in this geographic region will head to the 6th Circuit.

The number of judges in each circuit ranges from six judges in the 1st Circuit to 29 in the 9th Circuit. However, only three of these judges are randomly selected to form the panel that will decide the appeal. On rare occasions, after the three judge-panel makes a decision, a circuit court can rehear a case “en banc,” with the entire slate of judges reviewing the case.

The U.S. Supreme Court is the highest court and final level of appeal. It chooses which cases it hears.

Parties who disagree with the decision made by a circuit court can petition the U.S. Supreme Court to take the case. Less frequently, parties can petition the Supreme Court to review the decision made by a state Supreme Court if the case deals with a federal question.

Unlike intermediate appellate courts, the U.S. Supreme Court is not required to hear cases. Instead, parties ask the court to grant a writ of certiorari. The Supreme Court hears around 80 cases per year, selected from over 7,000 cases that it is asked to review.

There are no strict requirements for how the court selects its cases. It’s up to the discretion of the Supreme Court justices — four of the nine justices must vote in favor to accept a case. However, the Court typically accepts cases where there are conflicting decisions coming out of different circuits and/or there is a constitutional matter of national importance that needs to be resolved.

The state court system:

The state court system largely mirrors the structure of the federal court system in that it is generally composed of three main levels: trial courts, state appellate courts and a state Supreme Court. On rare occasions, a decision on federal matters made in a state Supreme Court will be petitioned to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Numerous states have separate probate courts focused on specific administrative matters. Each state runs its judicial system in a different way than its neighbor:

- For example, Colorado has subject-specific courts — on water, juvenile affairs in Denver, probate in Denver — as well as lower municipal and county courts.

- Meanwhile, the highest court in New York is called the Court of Appeals and the state’s Supreme Court is a trial-level court.

You can find the individual state courts’ structure and websites here.

While federal judges are nominated by the president, state judges are selected through various methods: governor or legislature appointments or elections. In 2022, there will be hundreds of judicial elections happening across the country where everyday residents can take a direct role in shaping the legal system.

Litigation is only going to ramp up this year. With this renewed understanding of the U.S. legal system, explore Democracy Docket’s Case pages and keep a close eye out for lawsuits that will determine the future of voting, elections and representation in the nation.