North Carolina Supreme Court To Rehear State-Level Redistricting Case Underlying Moore v. Harper

On Tuesday, March 14, the North Carolina Supreme Court will rehear Harper v. Hall, a previously decided redistricting case out of North Carolina. In its prior decisions in the case, the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down the state’s congressional and legislative maps drawn with 2020 census data for being partisan gerrymanders and later rejected the remedial state Senate map adopted by the Legislature.

Strikingly, the court’s unprecedented decision to rehear this case was not due to any changes in the underlying facts of the lawsuit; instead, it ensued after North Carolina Republican legislators asked for the case to be reheard following the state Supreme Court’s shift from a Democratic to a Republican majority after the 2022 midterm elections.

Importantly, Harper is the precursor to Moore v. Harper, the landmark case currently pending before the U.S. Supreme Court. Moore, while originally about North Carolina redistricting, ultimately seeks review of the radical independent state legislature (ISL) theory. The ISL theory asserts that under the Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution, only state legislatures can enact rules regulating federal elections, including congressional maps, without state-level judicial review. The North Carolina Supreme Court’s decision to rehear Harper, the underlying state-level redistricting case, could have implications for the fate of the ISL theory in Moore as well as for the future of redistricting and partisan gerrymandering in the Tar Heel State.

Below, we explain how the state court case, Harper v. Hall, and U.S. Supreme Court case, Moore v. Harper, are intertwined and what rehearing in Harper could mean for the future of the radical ISL theory currently pending before the nation’s highest court. When we mention Harper, we are referring to the state-level redistricting case. When we mention Moore, we are referring to the U.S. Supreme Court case.

Who is involved in the case?

In November 2021, individual voters, led by Rebecca Harper, and the North Carolina League of Conservation Voters filed two initial lawsuits challenging North Carolina’s legislative and congressional maps. These lawsuits were consolidated and Common Cause, a voting rights group, intervened. These parties oppose the North Carolina Supreme Court’s rehearing of Harper and request that the court affirm its previous decisions in the case. We will refer to these groups as the “pro-voting parties.”

North Carolina Republican legislators defended the legality of the challenged maps and asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review North Carolina state courts’ involvement in congressional redistricting by invoking the ISL theory. These parties also requested that the North Carolina Supreme Court rehear Harper and ask the court to overturn its previous decisions. We’ll refer to this group as the “Republican legislators.”

How did we get here?

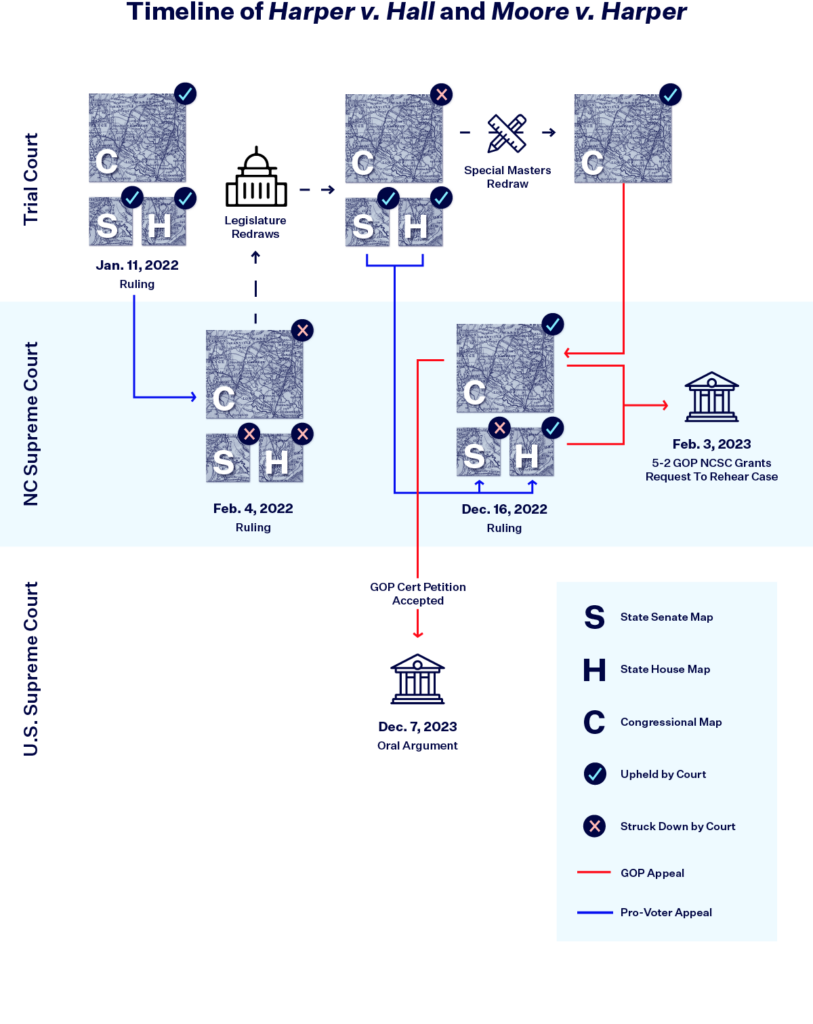

How is the rehearing before the state Supreme Court tomorrow connected to the ISL theory, and how did a typical redistricting lawsuit morph into the vehicle for a radical conservative legal theory that wound up before the U.S. Supreme Court? Harper and Moore have overlapping timelines that bounce between state court and the U.S. Supreme Court, which were further complicated when the North Carolina Supreme Court granted rehearing in Harper in early 2023. A basic timeline of the important points of Harper and Moore’s procedural history is summarized below.

- In November 2021, the pro-voting parties sued over North Carolina’s congressional and legislative maps drawn with 2020 census data for allegedly being partisan gerrymanders that violated the state constitution.

- On Jan. 11, 2022, a North Carolina trial court upheld all three maps, ruling that partisan gerrymandering claims are not justiciable (meaning they are not suitable for courts to rule on). The pro-voting parties then appealed this decision.

- On Feb. 4, 2022, on appeal, the North Carolina Supreme Court held that partisan gerrymandering claims are, in fact, justiciable and ruled 4-3 to strike down the legislative and congressional maps for being partisan gerrymanders that violated the North Carolina Constitution.

- On Feb. 23, 2022, in accordance with the state Supreme Court’s ruling, the trial court adopted new state House and Senate remedial maps passed by the General Assembly and an interim congressional map (for use only in the 2022 midterm elections) drawn by court-appointed special masters after rejecting the congressional map proposed by the General Assembly. We’ll refer to this ruling as the February 2022 decision.

- On Feb. 23, 2022, just hours after the remedial maps were adopted, various sets of parties appealed to the North Carolina Supreme Court. The pro-voting parties appealed the remedial state Senate and House maps enacted by the General Assembly and the Republican legislators appealed the court-drawn interim congressional map. The state’s highest court declined to pause the lower court’s adoption of the remedial maps while the appeal was litigated; this state-level appeal moved forward as the Republican legislators appealed the court-drawn interim congressional map to the U.S. Supreme Court.

- On Feb. 25, 2022, Republicans in the North Carolina Legislature filed an emergency application on the U.S. Supreme Court’s shadow docket invoking the radical ISL theory. The Supreme Court denied the emergency application on March 7, but a few months later in June agreed to hear the case on its full merits docket in order to review the ISL theory.

- On Dec. 7, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in Moore; a decision in the case remains pending.

- On Dec. 16, 2022, the then-Democratic majority of the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled 4-3 to block the remedial state Senate map, uphold the remedial state House map and affirm the trial court’s rejection of the General Assembly’s remedial congressional map. We’ll refer to this ruling as the December 2022 decision. The case then went back to the trial court for the drawing of a new state Senate map.

- On Jan. 1, 2023, two new Republican members of the North Carolina Supreme Court were sworn in. This shifted the majority on the court from Democratic to Republican.

- On Jan. 20, 2023, just 20 days after the court’s newly elected Republican majority was sworn in, the Republican legislators asked the court to reopen the case and overturn its February and December 2022 decisions.

- On Feb. 3, 2023, the North Carolina Supreme Court, in a highly unprecedented move, agreed to rehear the case.

What is each side arguing at tomorrow’s rehearing in Harper?

The Republican legislators who asked the North Carolina Supreme Court to rehear Harper argue that the court should “withdraw” its December 2022 decision. This decision struck down the state’s remedial Senate map for being a partisan gerrymander and affirmed the trial court’s rejection of the General Assembly’s remedial congressional map, which was ultimately replaced by a court-drawn interim map that was only in place for the 2022 elections. Additionally, they ask the court to “overrule” its February 2022 decision striking down the state’s original legislative and congressional maps enacted by the Legislature for being partisan gerrymanders.

The Republican legislators contend that the North Carolina Supreme Court’s February 2022 decision “invalidating the congressional map enacted by the General Assembly…conflicts with the U.S. Constitution’s Elections Clause” and that “[p]olitical gerrymandering claims are non-justiciable,” meaning they are not suitable for review by the state’s judicial branch. In addition to asking the court to eliminate partisan gerrymandering claims from its purview, the legislators ask the court to “permit the General Assembly to exercise its constitutional duties to draw new House, Senate, and congressional redistricting plans [for the next election cycle] free from” judicial interference.

On the other side, the pro-voting parties that oppose rehearing refute the arguments made by the Republican legislators, asserting that the legislators failed to provide the court with a valid basis for overruling its prior decisions regarding partisan gerrymandering. In addition to underscoring that “partisan-gerrymandering claims are justiciable,” the pro-voting parties point out that because the legislators “raise arguments resting on essentially the ‘same line of argument’ and the ‘same authorities’ previously raised in, and rejected by, this Court, they must again be rejected.”

Finally, the pro-voting parties push back against the Republicans’ request to redraw the state House, state Senate and congressional maps, noting that although the legislators are permitted to redraw the congressional and state Senate maps that were previously struck down, they are not permitted to redraw the state House map.

What’s next in the North Carolina Supreme Court following rehearing?

Following rehearing, the North Carolina Supreme Court could either grant, partially grant or deny the Republican legislators’ requested relief seeking to overturn the court’s prior decisions and to redraw the state’s congressional and legislative maps free from judicial review. In practical terms, this means that the North Carolina Supreme Court could affirm its prior decision striking down the challenged maps for being partisan gerrymanders that violated the state constitution and rule that partisan gerrymander claims are justiciable. On the other hand, the state Supreme Court could reverse its prior decisions striking down the challenged maps and instead rule that partisan gerrymander claims are nonjusticiable.

Crucially, if the state Supreme Court decides the latter, there might no longer be an avenue for litigants in North Carolina to bring these types of claims against the state’s electoral maps, with federal court review of partisan gerrymandering claims out of the question following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019). Alternatively, the state court could issue a decision neither wholly reversing nor affirming its prior decisions, but rather adopting some other approach to its rehearing decision.

What’s next in the U.S. Supreme Court following rehearing?

As of now, the effects of the state-level rehearing on the Supreme Court’s pending decision in Moore remain uncertain, but there are a few probable paths forward that the high court could take. Had the North Carolina Supreme Court’s newly elected GOP majority not agreed to rehear Harper, the trajectory of Moore would most likely adhere to a standard course of judicial review: The U.S. Supreme Court would review the constitutionality of the ISL theory stemming from the North Carolina Supreme Court’s final decision on the state’s congressional map. However, because the North Carolina Supreme Court is rehearing Harper, it is possible that its prior decision striking down the state’s congressional map — which served as the vehicle through which the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to review the ISL theory in Moore — is no longer a final decision that is suitable for review by the nation’s highest court.

Under federal law and prior Supreme Court precedent, the Court can only review final decisions from state courts. In light of this, in early March, the Supreme Court issued an order asking the parties in Moore to file additional briefs by March 20 addressing the question whether the Court still retains the legal authority to hear the case, in legal terms known as “jurisdiction.” Accordingly, the Court could issue an order regarding its jurisdiction to decide Moore at any time after March 20. Regardless of what the Court might decide, its recent order indicates that it is at least considering how the rehearing proceedings in state court might affect whether and when it issues a decision in Moore.

Alternatively, the Supreme Court could dismiss Moore as “improvidently granted.” In legal terms, this means that despite previously agreeing to hear the case, the Court could revoke its prior grant of certiorari that put the case on its merits docket and decide that it will not issue a final decision in the case. While the Court does not have to provide its reasoning for dismissing the case as improvidently granted, it could decide, for instance, that the convoluted nature of the proceedings in the North Carolina Supreme Court renders Moore an improper vehicle through which to decide on the merits of the ISL theory. If the Court ultimately decides to dismiss Moore for any number of reasons, it will not necessarily wait for a decision on rehearing from the North Carolina Supreme Court before doing so.

Indeed, if the U.S. Supreme Court dismisses Moore for jurisdictional reasons or as improvidently granted and declines to rule on the merits of the ISL theory, the status quo will remain in place — at least for now — insofar as state courts will still be able to review laws regulating federal elections, including congressional maps, enacted by state legislatures. However, a potential dismissal of Moore will not foreclose future review of the ISL theory by the Supreme Court; in fact, the Court is considering taking a case out of Ohio that raises the ISL theory.

The U.S. Supreme Court could still issue a decision at any time in Moore and rule on the constitutionality of the ISL theory despite the North Carolina Supreme Court’s rehearing of Harper. On the other hand, a majority of the Court could opt for a rarely used route and decide to withhold a decision in Moore until its next term, meaning it might not issue a decision on the ISL theory before the conclusion of its current term in late June or early July.

Whatever the U.S. Supreme Court and the North Carolina Supreme Court decide, the stakes for democracy couldn’t be higher.

The prospect of a U.S. Supreme Court decision in Moore following the North Carolina Supreme Court’s rehearing of Harper remains uncertain. Nevertheless, the fate of the anti-democratic ISL theory and the future of partisan gerrymandering and redistricting in North Carolina hang in the balance as decisions in both of these cases simultaneously remain pending.