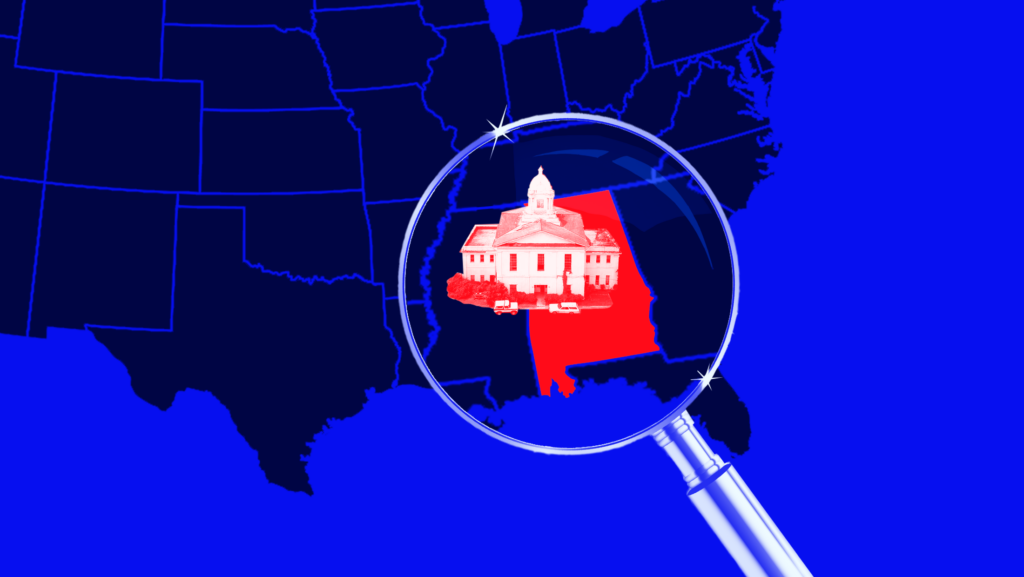

From School Boards to City Councils, Local Redistricting Matters

A 30 minute drive south of Birmingham, Alabama will bring you to Calera, a city with a population currently hovering around 17,000. Fifteen years ago, a decision made by the Calera city government sparked a chain of events that would ultimately alter the landscape of voting rights nationwide.

Calera officials decided to shift city council boundaries, effectively dismantling the city’s only majority-Black district by reducing the percentage of Black registered voters in the district from 70% to 30%. On Aug. 25, 2008, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) objected to this change under its authority from Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). Section 5 required states with a history of discriminatory election laws — a classification that included all of Alabama — to receive federal approval before enacting new voting changes.

It was too late for Calera. An election took place on Aug. 26, 2008 and the sole Black member of the city council was voted out of office under the new district plan. More back and forth with the DOJ ensued until April 2010, when the county in which Calera is located filed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the entire Section 5 scheme.

Calera’s home county, Shelby County, became known for the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case it engendered: Shelby County v. Holder (2013).

The chatter around redistricting often focuses on the partisan breakdown of the U.S. House or hyper-gerrymandered state legislatures across the county. However, almost every jurisdiction — no matter how big or small, from school boards to water districts — undergoes some sort of line drawing process. The fact that a small city’s redistricting skirmish led to the gutting of a central portion of the federal VRA should serve as a reminder to not overlook local redistricting.

Last week, two big cities saw updates in lawsuits challenging local council districts.

The release of 2020 census data has triggered a fresh wave of redistricting lawsuits, including at the county and city level where fights over representation can be hyper localized and especially impactful.

On May 8, 2023, a federal judge ordered the city council in Boston, Massachusetts to draw new districts. The judge found that “race played a predominant role in the City Council’s redrawing” of two of the districts — a phenomenon known as racial gerrymandering — in a likely violation of the 14th Amendment. It was a unique ruling though, as the judge took issue with Boston councilors overemphasizing racial equity, citing quotes that claimed that the council was “making sure that racial minorities have the opportunity to have strong political power.”

“This might be the first racial gerrymandering case where the violation was purely the race-based transfer of white voters from one district to another,” redistricting expert Nicholas Stephanopoulos wrote on Twitter in response to the ruling.

The next day, May 9, 2023, civil rights groups in Jacksonville, Florida witnessed a very different win. After a string of losses in court, the Jacksonville City Council finally agreed to a settlement for city council and county school board districts.

“We had a very strong case of racial gerrymandering that’s been going on in that city for decades,” Nick Warren, a staff attorney with the ACLU Florida who worked on the case, told Democracy Docket. “Losing over and over and over again, the city realized that it was time to come to the table and talk to us about what it would take to end the case.”

The map that the Jacksonville City Council adopted last spring packed Black voters into just four of the 14 council seat districts. “That stripped Black voters from surrounding districts, diminished their influence there and really contributed to a culture of unresponsiveness that crosses party [and racial] lines in the city,” Warren explained. “Challenging this redistricting was an opportunity to try to spur some change in city hall.”

The court-adopted map proposed by plaintiffs — a coalition of community groups that included the Jacksonville Branch of the NAACP and the Northside Coalition of Jacksonville — not only improved representation for Black residents, it kept communities together. Warren emphasized this point: “It didn’t make sense to have these sprawling, tortured districts that snaked from one end of the city to the other because those communities didn’t have anything in common, except for the color of their skin. The court ordered map that we submitted has more compact districts that respect neighborhood boundaries.”

Boston and Jacksonville are just two of many jurisdictions with challenged maps after the 2020 census.

Through the end of 2022, there were 87 total lawsuits that challenged congressional or state legislative maps drawn with 2020 census data. The national media covered these wins and losses in court, keeping close track of the number of seats gained or lost by Democrats and Republicans. A host of other suits flew under the radar, focusing on city or county-level governing bodies.

In addition to Boston and Jacksonville, redistricting lawsuits that made claims under Section 2 of the VRA or the 14th Amendment were filed in Jefferson County, Alabama; Miami, Florida; Baltimore County, Maryland; Thurston County, Nebraska and Galveston County, Texas (even the DOJ got involved here). From New York City to San Luis Obispo County, California, numerous other lawsuits challenged local redistricting for state law or city charter violations.

“This is a 1960s-style fight for democracy,” Galveston County Commissioner Stephen Holmes (D) told The Texas Tribune last year. The Republican majority on the commissioner’s court dismantled Holmes’ district where Black and Latino voters regularly voted together to support candidates like Holmes, the only Democrat and nonwhite member on the commissioner’s court. This action caught the attention of the DOJ, which is now involved in a lawsuit in the coastal county located just southeast of Houston.

Additionally, lawsuits regularly challenge at-large elections, a method where voters cast ballots for all the candidates in a jurisdiction. Following the 2020 census, there were local challenges to at-large districts in Dodge City, Kansas; West Monroe, Louisiana; Benson County, North Dakota; Houston, Texas; Virginia Beach, Virginia and Franklin County, Washington.

In a press release, a plaintiff in the Benson County, North Dakota lawsuit noted: “Native voters now have a meaningful chance to participate in local government in the county, because of the Native people who spoke up to defend our rights as voters.”

“[A] violation is just as important in a small rural area as it would be in a major competitive state or city.”

With the knowledge and comfort that other state and national organizations would focus on congressional and legislative maps, the ACLU of Florida made an intentional choice at the onset of the 2020 redistricting cycle to focus on local redistricting.

Warren explained that the strategy had two prongs: The ACLU of Florida first prioritized organizing and public education to ensure governing bodies passed fair maps. Only after lobbying efforts were exhausted, as they were in Jacksonville and Miami, did the group file lawsuits.

In smaller jurisdictions, the advocacy work was more successful in changing outcomes, Warren added. “We worked really collaboratively with elected officials — county commission, city commission, school board members — throughout North Florida in mostly small counties and small cities to enforce and maintain districts that are mandated by the Voting Rights Act,” he described.

Warren also gave credit to the extensive reporting by Jacksonville’s local newspaper, The Tributary, as another crucial resource.

“A good journalist really can attract a lot of attention to local redistricting, and state and local media often write the best, most detailed stories about redistricting,” explained Jay Fierman, the one man show behind the popular Redistrict Network Twitter account, which provides news updates on the 2020 redistricting cycle. “Local journalists will often go into specifics about metrics and process while it is common for national media to focus on [the] horse-race.”

In a comment to Democracy Docket, Fierman added that he relies on other community partners to stay up-to-date. This includes the New York Census and Redistricting Institute at New York Law School, a program run by redistricting lawyer Jeff Wice.

“It’s important to monitor and track redistricting in as many places as possible,” Wice told Democracy Docket. “[The] Institute was created, in part, to track and monitor redistricting at every level across the state.”

Wice pointed to Baker v. Carr (1962), one of the most consequential Supreme Court redistricting cases of the 20th century, which emerged from Tennessee’s inaction around state legislative lines. “[T]he most important redistricting case can develop in a small town that does not get much media attention,” he continued. “An equal population or Voting Rights Act violation is just as important in a small rural area as it would be in a major competitive state or city.”