Friend or Foe: Analyzing Amicus Briefs in Moore v. Harper

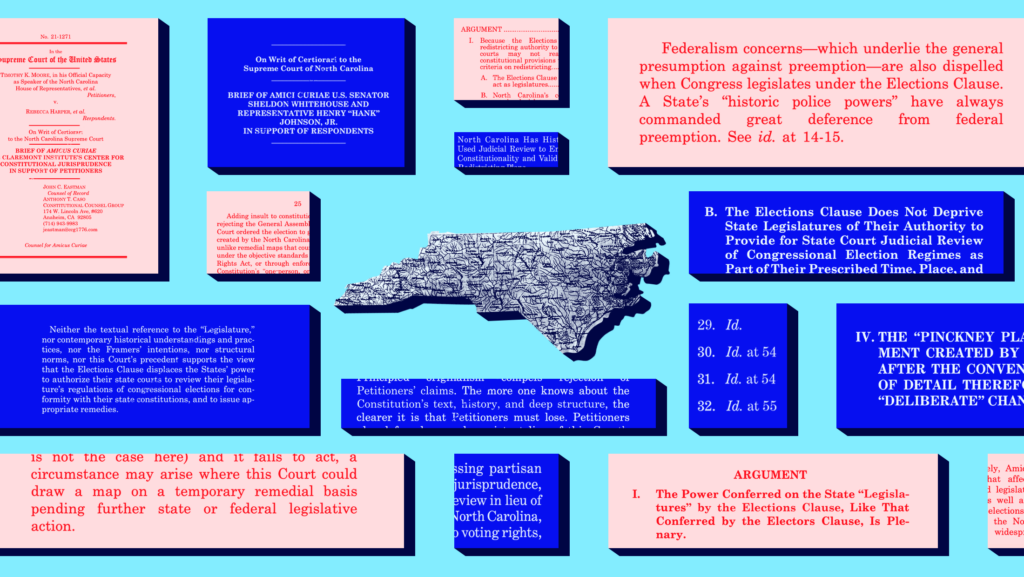

On Dec. 7, the U.S. Supreme Court will hold oral argument for Moore v. Harper, a notable case with high stakes for democracy. The case gives the Supreme Court the opportunity to review the fringe independent state legislature (ISL) theory, which argues that state legislatures have special authority to set federal election rules free from interference from other parts of the state government, specifically state courts. The ISL theory relies on the language in the U.S. Constitution’s Elections Clause, interpreting the word “legislature” to mean state legislatures — and only state legislatures.

Moore v. Harper is the vessel for right-wing organizations and politicians to advance this constitutional theory that has never been embraced — and actually rejected several times — by courts. The case comes out of North Carolina, where the Republican-controlled Legislature drew new congressional and legislative maps after the release of 2020 census data. The North Carolina Supreme Court struck down these maps for being partisan gerrymanders that violated the state constitution. After giving the Legislature the first opportunity at a redraw, a court-appointed redistricting expert then constructed a fairer congressional map. The Moore parties — the North Carolina Republicans who petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to take the case — invoke the ISL theory to argue that the North Carolina Supreme Court improperly limited the Legislature’s redistricting authority. The Harper parties — Common Cause, North Carolina League of Conservation Voters and individual voters — rebuke this argument, including the faulty historical claims put forward by the Moore parties.

Even before the lawyers head to the courtroom on Dec. 7, amicus curiae “friend of the court” briefs reveal the competing priorities of the two sides and expose the high stakes of this case. These briefs come from individuals or organizations that are not parties in the case but have interests in the outcome. The number of amicus briefs and the frequency of U.S. Supreme Court justices citing them in final decisions has increased over the past few decades. In a 2021 law review article, U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) discussed this phenomenon and concluded that the “amicus brief is now a powerful lobbying tool for interest groups.”

A total of 69 amicus briefs were submitted — 16 in support of the Moore parties that embrace the ISL theory, 48 in support of the Harper parties that repudiate the ISL theory and five in support of neither party. After reviewing all 69 amici, we’re highlighting a handful of the most insightful, provocative or compelling briefs.

Here are some briefs in support of the Moore parties and North Carolina Republican lawmakers.

The briefs in support of the Moore parties urge the Court to adopt the ISL theory, to varying degrees of intensity. Some of the notable groups and individuals who submitted briefs in favor of the ISL theory include the America First Legal Foundation (a group founded by Stephen Miller and Mark Meadows, high level staffers of former President Donald Trump), Citizens United, Honest Elections Project (a group linked to Leonard Leo, a longtime Federalist Society leader and right-wing funder) and 13 Republican state attorneys general.

The Republican National Committee (RNC), National Republican Congressional Committee and North Carolina Republican Party

Establishment Republican institutions fall on the side of embracing the ISL theory. However, the RNC’s brief presents itself as a middle ground approach, trying to speak directly to the justices about the “overblown reaction this case has engendered.” The Republican groups argue that federal courts — not state courts — are the appropriate arena to adjudicate cases related to federal election laws and congressional redistricting. Notably, the RNC argues that “the Constitution itself, along with federal statutes, already impose multiple safeguards that would otherwise prevent a state legislature from overturning valid federal election results,” responding to concerns about how bad faith actors could use the ISL theory to subvert elections.

Claremont Institute’s Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence

In contrast, the Claremont Institute, a conservative think tank, takes an extreme position on the ISL theory in its brief. The document was written and submitted by John Eastman, Trump’s legal advisor and a central figure in the attempts to overturn the results of the 2020 election. In fact, Eastman used the most radical version of the ISL theory to advance his argument before Jan. 6, 2021: In a memo, he spelled out a frightening, unconstitutional plan of how then-Vice President Mike Pence could declare Trump the winner of the Electoral College and the presidency.

Unsurprising given its author, Eastman’s amicus brief in support of Moore states that the power conferred to state legislatures by not only the Elections Clause, but also the Presidential Electors Clause, is “plenary,” meaning absolute. The ISL theory is inconsistent with cases from the past century, the brief writes, so the suggested solution is to simply overturn three decisions: Ohio ex rel. Davis v. Hildebrant (a 1916 case about citizen referendum), Smiley v. Holm (a 1932 case about gubernatorial veto power) and Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (a 2015 case about Arizona’s independent redistricting commission). All three cases rejected the idea that the word “legislature” in the Elections Clause precluded lawmaking power vested within other entities when it came to congressional redistricting — citizen ballot measures, governors’ vetoes and independent commissions. Eastman thinks it is incorrect to permit these other lawmaking bodies to have any authority related to federal elections.

Other highlights:

- The Republican caucus of the Pennsylvania Senate submitted a brief that focuses on the “undesirable outcomes” from Pennsylvania state court judges. The brief is particularly resentful of two cases — Carter v. Chapman and League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania v. Pennsylvania — where the state Supreme Court either imposed fair redistricting maps in light of government deadlock or struck down a map for being an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. Not every state court that has been presented questions of partisan gerrymandering has found these questions justiciable and not every state court has interpreted the free and equal elections clause within their state constitution to bar such gerrymandering — but Pennsylvania, like North Carolina, has.

- Arkansas and Arizona led 11 other states in an amicus brief that similarly laments state court judges who take on a “policymaking” role. Yet, at the same time, the group of Republican attorneys general praise the way that the Arkansas Supreme Court has interpreted its state constitutional provision governing free elections, stating that “the Arkansas Supreme Court has read that language to solely prohibit ‘fraud and [voter] intimidation.’”

- The American Legislative Exchange Council — a conservative group that drafts model legislation for state legislators across the country — alleges that, since there’s no objective way for state courts to determine a partisan gerrymander, courts have “usurped the policymaking role and ‘indefinitely retains the redistricting authority, thereby enforcing its policy preferences.’” Notably, the brief equally critiques the Maryland Supreme Court for striking down a Democratic partisan gerrymander earlier this year.

Here are some briefs in support of the Harper parties.

Amicus briefs in favor of the Harper parties were due a few weeks ago and reached a significant high of 48. These briefs argue in favor of upholding the North Carolina Supreme Court’s decisions to strike down and order a redrawing of the state’s gerrymandered congressional map and argue against any embrace of the ISL theory. Some of the notable groups and individuals who submitted amicus briefs include civic and racial justice groups, including the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, LatinoJustice, NAACP and Native American Rights Fund, a group of 20 senators led by U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), 13 Democratic secretaries of state, 22 Democratic state attorneys general, former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger (R), former elected and appointed Republican officials, retired members of the U.S. Armed Forces and numerous historians and legal scholars.

Additionally, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) submitted an amicus brief explaining the position of the United States. The DOJ does not raise any novel points, but gives a full repudiation of the ISL theory. “Text, historical context, longstanding practice, and this Court’s precedent all establish that the Clause does not thereby authorize legislatures to ignore the state constitutions that created them,” the brief emphasizes.

Professors Akhil Reed Amar and Vikram David Amar and Federalist Society Founder Steven Gow Calabresi

In one of the more scathing amicus briefs, constitutional law professors (and brothers) Akhil Reed Amar and Vikram David Amar are joined by Steven Gow Calabresi, an original founder of the Federalist Society, a conservative legal organization that has been instrumental in the judiciary’s rightward turn. The Amars have previously written widely cited research debunking the ISL theory. In this amicus brief, the trio bases their argument against the ISL theory in the preferred method of the conservative members of the Court: originalism. “The more one knows about the Constitution’s text, history, and deep structure, the clearer it is that Petitioners must lose,” the brief reads early on.

As many other amicus briefs in support of the Harper parties also outline, the Amars and Calabresi give evidence to support the idea that the founders viewed state legislatures as a body inherently constrained by state constitutions. “Prominent state judicial review under state constitutions predated the Philadelphia Convention, The Federalist No. 78, and Marbury v. Madison,” the brief says, pointing to sources during the founding era. “Indeed, state constitutions formed the basic template for the federal Constitution.” After describing how the founding generation understood “legislature” to mean a lawmaking system, the brief adds that, in response to the Moore parties’ request, “the Court should remain true to bedrock principles of federalism and institutional modesty.”

Finally, the brief makes the interesting point that if the ISL theory logic were to prevail regarding the Elections Clause in Article I, that would mean it would definitely not apply to the Presidential Electors Clause in Article II. “Unlike Article I, Article II makes each state, not ‘the legislature thereof’ the empowered actor,” the brief reads. “That is, ‘each state’— not each state ‘legislature’ —is authorized and obligated to appoint presidential electors.”

Scholars of the Founding Era

A group of professional historians and law professors explores the historical origins of the Elections Clause. Their amicus brief provides evidence for the assertion that “[h]istorians have many explanations of the origins of the Constitution. Yet nearly every scholar of this subject agrees that disillusionment with the performance of the state legislatures was the dominant concern that led to the Federal Convention.” Consequently, the Founders would not have wanted to give state legislatures unchecked powers. Additionally, the scholars point to the “famously misleading document” that the Moore parties rely on as a central source of historical authority to argue that the Founders considered broader language in the Elections Clause before landing on the word “legislature.” In fact, this document, known as the Pinckney Plan, was “written at least a decade after ratification” of the Constitution, leading the Moore parties to “construct a false narrative and an invented imputed intent.”

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund

In its amicus brief, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund focuses on the impact of partisan gerrymandering on voters of color. “The 2020 census revealed that the nation’s population continues to become increasingly diverse, with immigrant populations and populations of color growing the most rapidly,” the brief reads. “Yet extreme gerrymandering, renders what should be the most democratically responsive branch of government resistant to these changes, insulating legislators from the evolving demographics of their States and the political preferences of their voters. Should the Court adopt Petitioners’ view of the Elections Clause, history teaches that voters of color will inevitably be caught in the crossfire.”

Boston University Center for Antiracist Research and Professor Atiba Ellis

An amicus brief filed by Professor Atiba Ellis similarly argues about the particularly destructive impact of the ISL theory on Black voters and voters of color. “When state legislatures have unchecked power to govern elections with impunity, history tells us that the voting rights of people of color will be undermined,” the brief explains before diving into the “struggle for an inclusive and authentic democracy in North Carolina.” The recent history includes North Carolina courts repeatedly striking down racially gerrymandered maps, partisan gerrymandered maps and racially discriminatory voting restrictions. The brief also makes the important note that it was the North Carolina Legislature itself that, in 2003, created a procedure for redistricting plans to be challenged in court and specifically empowering the courts to remedy any maps.

Current and former election administrators

A group of election administrators wrote an amicus brief that mirrors several other briefs in highlighting the practical implications of the ISL theory on running elections. The administrators warn that embracing the ISL theory would open up numerous state laws, constitutional provisions, administrative rules and ballot measures to new federal litigation. If decisions related to federal elections were constrained to the state legislature only, the brief says it would also severely curtail discretionary orders made by governors, secretaries of state or expert local administrators in case of unforeseen circumstances, such as natural disasters. Finally, the brief stresses that the ISL theory could create two separate sets of rules for state and federal elections. “Conducting concurrent federal and state elections under a common set of rules is vastly more efficient and cost-effective, and far less prone to error and confusion,” the brief writes. In contrast, the “ISL claim would threaten the ability of state and local governments to run concurrent federal-state elections.”

U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) and Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.)

The amicus brief submitted by Whitehouse and Johnson focuses on the dark money funding of amicus briefs and its dangerous impact on democracy and the Court’s legitimacy. Their brief specifically calls out the amici submitted in support of the Moore parties that argue in favor of the ISL theory, adding that the “Court should tread carefully before giving credibility to these theories of election subverters and vote suppressors.” Whitehouse and Johnson connect the thread between the failed lawsuits brought in the aftermath of the 2020 election and the case now before the Supreme Court. They point out that many of the same actors involved in those attempts to subvert the 2020 presidential election are now supporting the ISL theory in Moore v. Harper: “participants in those efforts appear here as amici, unabashed, but also undisclosed.”

Other highlights:

- The Brennan Center for Justice’s amicus brief collates the startling numbers that show the wide, potentially destabilizing reach of the ISL theory. The group writes that if adopted, the ISL theory could impact “hundreds of state constitutional provisions,…hundreds of state court decisions…and over a thousand delegations of authority.” The brief then runs through numerous examples ranging from court decisions on drop box placement in Ohio and ballot counting in Maryland to the eight states that have modified voting methods via ballot measures.

- FairDistricts Now discusses Florida’s Fair Districts Amendment (FFDA), a 2010 citizen initiative that prohibits partisan bias in drawing district lines. The brief points to Rucho v. Common Cause, where the Court praised the FFDA as a constitutional effort to curb partisan gerrymandering through constitutional provisions and state court enforcement. FairDistricts Now argues that there is no reasonable way to allow Florida courts to enforce the FFDA and not allow North Carolina courts to enforce their constitutional provisions. “No valid basis exists to distinguish this case,” the brief notes, adding that the “Petitioners’ proposed dichotomy of ‘openended’ and ‘specific’ constitutional provisions is utterly unworkable.”

- Three law professors — Carolyn Shapiro, Nicholas Stephanopoulos and Daniel Tokaji — argue that despite attempts by Moore parties to distinguish between past precedent and this case, the Court must reject any version of the theory. “Petitioners create their own unmanageable requirement that courts distinguish between vague and non-vague constitutional provisions,” the brief states, going on to explain how unworkable that standard, or any other line the Court may attempt to draw, would be.

Here are some briefs in support of neither party.

Compared to the numerous briefs submitted on behalf of either side, only a few groups submitted briefs in favor of neither party, refusing to weigh in on the specifics of the North Carolina redistricting case and instead commenting on other legal aspects of the ISL theory. For example, one brief makes a novel argument that, under the ISL theory, President Joe Biden’s Executive Order 14019, a pro-voting executive order issued in March 2021, and the Electoral Count Act, an 1887 law that governs the counting of presidential electoral votes in Congress, are potentially unconstitutional. In another brief, Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft (R) argues that redistricting does not fall within the “Manner of holding Elections,” as used in the Elections Clause. A third brief in support of neither party argues for a different standard than what the Moore parties put forward — in effect, creating a middle ground standard where the North Carolina Supreme Court ruling is overturned, but constitutional anti-gerrymandering language, like that in Arizona and New York, is preserved.

The Conference of Chief Justices

A bipartisan group of state Supreme Court justices submitted a brief in support of neither party that flatly rejects the ISL theory’s interpretation of the Elections Clause: “Neither the textual reference to the ‘Legislature,’ nor contemporary historical understandings and practices, nor the Framers’ intentions, nor structural norms, nor this Court’s precedent supports the view that the Elections Clause displaces the States’ power to authorize their state courts to review their legislature’s regulations of congressional elections for conformity with their state constitutions, and to issue appropriate remedies.”

The chief justices emphasize that state court judgments, “while a form of check on the legality of lawmaking, [are] not itself lawmaking” and warn against intruding on state courts’ ability to interpret state law and state constitutions. The brief adds that federal review of state court decisions in this realm should respect state court decisions and defer to those outcomes in all but the most extraordinary circumstances.

Find all of the court documents, including amicus briefs, here. Oral argument will take place before the U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday, Dec. 7 at 10 a.m. EST. We will provide live updates during oral argument.