We Are Not Counting Every Vote

There is a saying among recount lawyers that “every ballot tells a story.” While most voting rights lawyers focus first on voter registration and the voting process, recount lawyers begin their work by looking at the ballots rejected by the vote counting process and try to unravel the stories behind them.

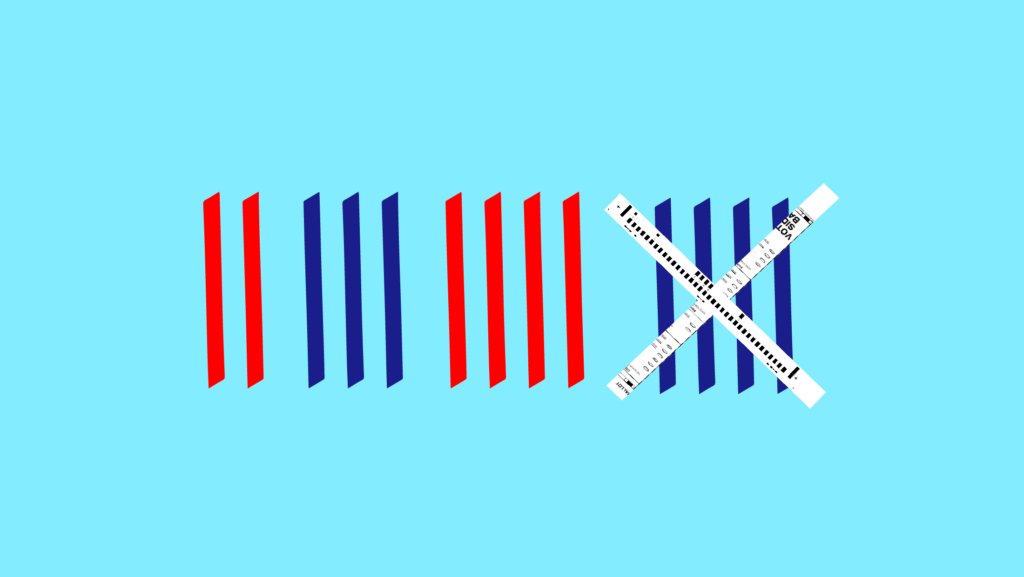

When you approach the voting process in this way — by first looking at what votes are left uncounted — a very different picture emerges of how voters are disenfranchised. Put simply, we have an epidemic of uncounted ballots. In every election, hundreds of thousands of voters nationwide are given the right to vote but not the right to have their vote counted. This creates a dangerous illusion of democracy. Like the crosswalk button a pedestrian presses that doesn’t actually affect the timing of the light changing, our voting laws have created an illusion for many voters that their votes are counting towards the outcome of elections.

In 2018, for example, 68,000 eligible voters nationwide had their mail-in ballots discarded because an election official, likely with no training, concluded that the voter’s signature on the ballot return envelope did not match the voter signature on file. Another 56,000 voters had their votes discarded because they simply forgot to sign the ballot return envelope. Many of these voters were never told that their vote did not count or given an opportunity to dispute the rejection or cure it.

Rejections of mail ballots are not the only way voters are silently disenfranchised. Another is through the use and misuse of provisional ballots. Provisional ballots were put into law as part of the 2002 Help America Vote Act. The idea was to provide a safety net for individuals who show up to vote but do not appear in the poll books. The law mandates that those individuals be given the right to vote a provisional ballot so that election officials can spend the time after election day to determine if the vote should count. In practice, many states have turned this safety net into a trap that results in lawful voters having their ballots discarded.

In 2018, more than 1.8 million voters were told by their election officials to cast a provisional ballot. Of those, nearly 385,000 voters ended up casting a ballot that never counted. The reasons for these rejections can be complex, but one big reason stands out. In 27 states, if an otherwise eligible registered voter shows up at the wrong polling location, she is given a provisional ballot that is then automatically rejected. In 2018, 24% of rejected provisional ballots were cast by voters who were properly registered in the state but attempted to vote in the wrong place. The result is that more than 92,000 otherwise lawful voters were given the illusion of democracy but had their ballots rejected, even for the portion of their ballots cast for statewide offices for which they were unquestionably eligible to vote.

Any election official will tell you that voting is messy. Voters often sign their name differently when they are in a hurry, or their signature changes as they age or their medical condition changes. Sometimes voters get confused and forget that they vote at the local high school and not the closer middle school, or only have time enough on their lunch hour to vote at the polling location near their work rather than the one near their home.

Unlike improper voter registration purges, there is no public outrage for the victims of faulty signature matching or out-of-precinct voters whose ballots are discarded. Yet these are election administration issues that are easily fixed ― if states want to fix them.

After its signature matching and cure process was successfully challenged in court, Florida revamped its law to ensure voters received notice of a problem with their signature by email, text or phone, and then had an extended period during which the voter could cure the ballot flagged for signature mismatch. The state also mandated formal signature matching training for election workers and made clear that all determinations of a signature mismatch be made by majority vote of the canvassing board and must be beyond a reasonable doubt. Though far from perfect, Florida’s new process is a good step in the right direction.

The fix for out-of-precinct voters is even simpler — permit a ballot cast in the wrong precinct to count for any statewide election. A state could permit more — such as allowing the ballot to count for other races for which that voter was eligible to vote — but there is no reason why the ballot should not count for president, U.S. Senate or other statewide offices. This is the rule in many states, but it should be the rule in all states.

These common-sense solutions will enfranchise thousands of lawful voters, improve the accuracy of our elections and reduce the need for costly post-election recounts — because fewer ballots will have a story that needs to be told.