The For the People Act’s Missing Piece

Georgia has been on the country’s mind lately. And not for a good reason. In March, the state passed one of the most sweeping sets of voting restrictions in recent memory.

Among other things, Senate Bill 202 bars absentee ballot applications from being sent to all voters. It imposes an ID requirement for absentee voting. It slashes the number of ballot drop-off boxes in Georgia’s biggest counties. It forbids mobile voting centers. It stops ballots cast in the wrong precinct from being counted. It criminalizes offering food or water to voters waiting in line. It gives the legislature control over the State Elections Board. It authorizes that Board to suspend county election officials. And so on.

For many voting rights advocates, the solution to laws like Georgia’s is clear: Congress should pass the For the People Act, the omnibus electoral reform bill recently approved by the House. And it’s true, the Act would override several of Georgia’s new limits. For example, the Act would mandate that absentee ballot applications be sent to all eligible voters. The Act would also prohibit ID requirements for absentee voting. And the Act would compel about five times more drop-off boxes than are allowed under Georgia’s law.

But the For the People Act wouldn’t invalidate all of Georgia’s new restrictions. It wouldn’t reach the ban on mobile voting centers. Nor would it reverse the criminalization of helping hungry or thirsty voters. Left standing, too, would be the legislature’s takeover of the elections board. The reason for these omissions is the Act’s underlying strategy. It specifies many steps that states must take to make voting easier, and it outlaws many policies that hinder voting. But it doesn’t include any catch-all provision applicable to all voting limits — including ones Congress hasn’t yet imagined. The Act thus leaves open the door to novel barriers erected by wily vote suppressors.

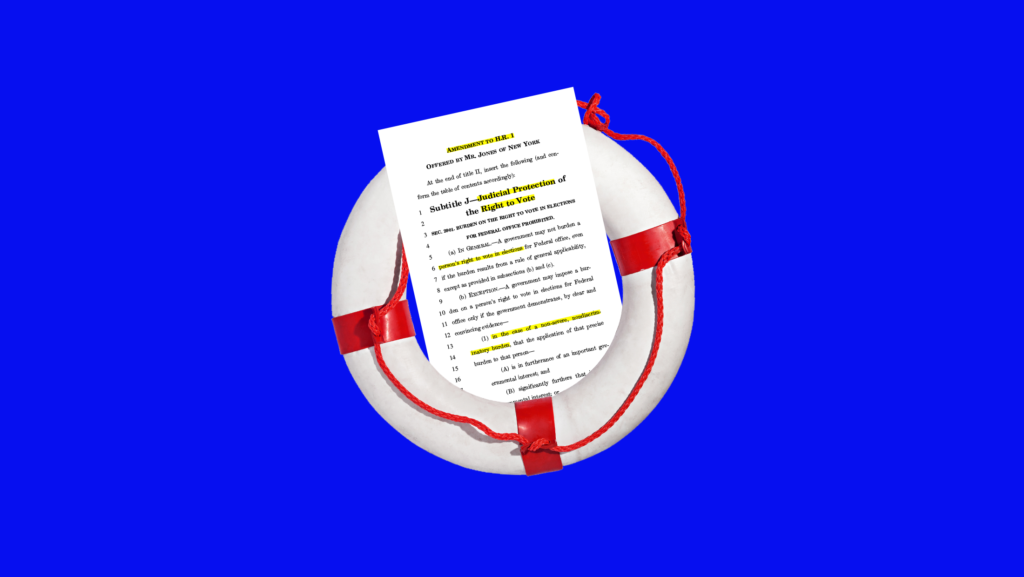

Rep. Jones’s amendment would eliminate the For the People Act’s blind spot with respect to new kinds of voting restrictions.

How could the Act slam this door shut? The most promising proposal is an amendment drafted by Rep. Mondaire Jones (D-NY). Under this amendment, any regulation that imposes a “severe or discriminatory burden” on voting in federal elections would be unlawful unless a jurisdiction could prove that the rule is the least restrictive way to further a compelling state interest. (Lawyers call this strict scrutiny.) Any regulation that imposes a milder voting burden would also be invalid unless it significantly furthers an important state interest. (This is intermediate scrutiny in legalese.)

Rep. Jones’s amendment would eliminate the For the People Act’s blind spot with respect to new kinds of voting restrictions.

Take the elements of Georgia’s law that would be unaffected by the Act as it currently stands. Rep. Jones’s amendment would reach those policies. All of them burden voting to some degree — potentially to an extreme degree if Georgia’s legislature uses its new powers to discard lawfully cast ballots. So the policies would be upheld only if Georgia could convince a court that they’re sufficiently linked to a vital enough interest.

But it’s implausible that Georgia could make this showing. The absence of widespread fraud attenuates the rationale for harsh new anti-fraud measures. There’s also no evidence that banning mobile voting centers, leaving hungry or thirsty voters to their own devices and authorizing the legislature to run elections boost electoral integrity. In fact, these steps probably undermine people’s confidence in the electoral system.

Rep. Jones’s amendment has advantages, too, over another catch-all approach to vote suppression: reviving the portion of the Voting Rights Act nullified by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013. Under that part of the VRA, certain jurisdictions (mostly in the South) had to prove that their electoral changes weren’t racially discriminatory before the changes could go into effect. In contrast, Rep. Jones’s amendment would apply nationwide, not just to a handful of states. It would also extend to all voting burdens, not just those with racial motives or effects. And it would work through ordinary litigation, as opposed to the extraordinary process of federal preclearance. These points could make Rep. Jones’s amendment more effective and less controversial. At the very least, it would nicely complement a VRA reauthorization.

Is it constitutional, though, for Congress to require heightened judicial scrutiny for all burdensome regulations of federal elections? Without a doubt. The Elections Clause grants Congress essentially plenary power over the “Manner of [congressional] elections.” Even the Roberts Court — no friend of expansive congressional authority — has conceded that, under the Clause, Congress could “provide a complete code for congressional elections.” It’s also unremarkable for Congress to use the Clause to create new bases for lawsuits. Earlier electoral statutes in the 1990s and 2000s did exactly that.

Likewise, it’s irrelevant that Rep. Jones’s amendment is more rigorous than the constitutional standard for right-to-vote claims. Under that standard, strict scrutiny is reserved for voting burdens akin to disenfranchisement and courts analyze most policies quite deferentially. Crucially, by relying on the Elections Clause to pass Rep. Jones’s amendment, Congress wouldn’t be trying to change the content of the constitutional doctrine. Instead, Congress would be instituting a new statutory regime grounded in Congress’s supervisory power over congressional elections — not in the constitutional right to vote. The divergence between the statutory and the constitutional rules would thus be immaterial.

That said, dissatisfaction with the constitutional rule is certainly a driver of Rep. Jones’s amendment. In the runup to the 2020 election, the Roberts Court upheld one voting restriction after another. Over its entire history, the Roberts Court has never ruled in favor of a plaintiff alleging an undue burden on her right to vote. Rep. Jones’s amendment is necessary, then, because today’s courts all too often fail to protect the franchise. Their dismal record is the impetus for congressional intervention.

Nicholas Stephanopoulos is a Professor of Law at Harvard Law School.