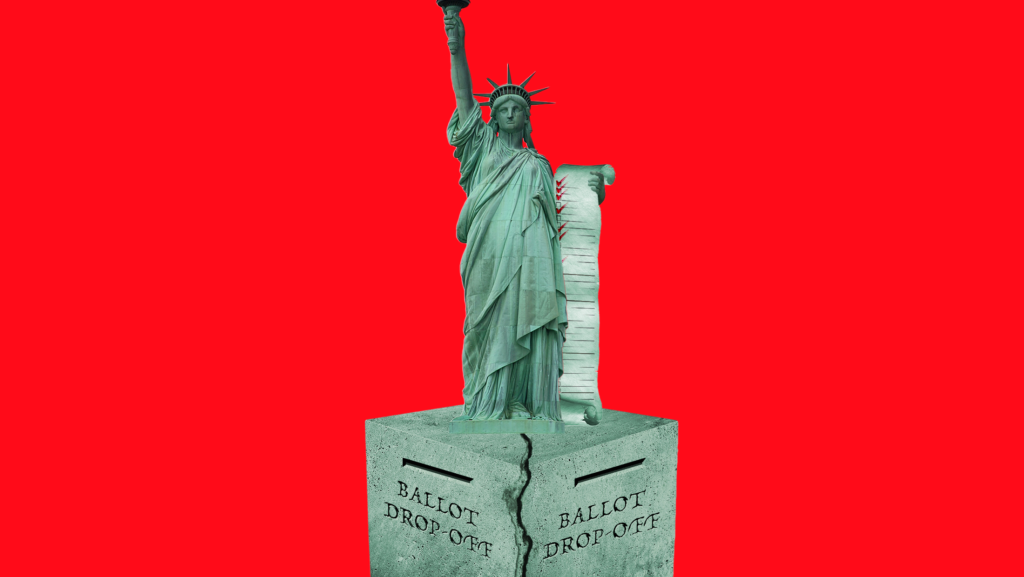

What Barriers to Citizenship Mean for Voting Rights

It’s Fourth of July weekend — a holiday to celebrate our country’s declaration of nationhood and the birth of what would become the United States of America. Central to the founding principles of our nation is the concept of equal, individual rights, including the right to representative government. But, at the time the Declaration of Independence was signed, there was no distinction of “citizenship” that limited those rights. The concept of citizenship as we know it today was not fully formed — and the ways in which citizenship and voting rights interact have gone through significant changes over the last century. As the holiday encourages us to reflect on our freedom, we’re examining how the barriers to becoming a citizen limit who is eligible to vote — and what that means for the democratic process.

The discussion around voting rights and the fight to protect them rests on one foundational truth: In America, (for the most part) only citizens can vote. In a country of immigrants, this is an incredibly important distinction — as of 2020, over 44 million immigrants were living in the U.S., comprising 13.7% of the population. For undocumented immigrants, the path to citizenship can be next to impossible. For documented immigrants and permanent residents, it can be an arduous and incredibly long process — and many simply choose to never attempt it. But for the foreign-born population of the United States, pursuing citizenship spells the difference between being able to vote for their representatives or not — no matter how long they have lived in the country.

As with most things in American life, the history of noncitizen voting rights is a history of state laws, divergent and independent from any federal standard. According to a research paper written by then-American University law professor and now-Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), for the first hundred or so years of our history “alien suffrage figured importantly in America’s nation-building process and in its struggle to define the dimensions and scope of democratic membership.” The United States was figuring out both how to continue to attract new immigrants and how to unify an already hugely diverse population, made up of large numbers of foreign-born immigrants and granting voting rights to new immigrants was an efficient and effective way to increase their sense of belonging and help build a collective American identity. As such, white men, regardless of citizenship status, had the right to vote in over 22 states before World War I.

Raskin credits this expansion of suffrage to a malleable definition of what citizenship was — not as a legal distinction, but as a social concept. “In choosing to confer the rights of political membership on aliens,” Raskin writes, “these states were recognizing meanings of citizenship apart from the notion of mere membership in the nation-state.” Citizens were members of society who were present in the day-to-day life of a state — and extending this definition to include those who joined only recently was important in order to assimilate new immigrants to the cultures and communities of the state. However, the definition of citizen quickly hardened as America entered World War I. Anti-immigrant sentiment and rampant xenophobia led many states to modify their constitutions and exclude noncitizens from suffrage despite expanding ballot access for female citizens across the country. In 1928, the United States held a national election where noncitizens were ineligible to vote at every single level of government. This new standard has more or less remained the same in the decades since.

The United States is not unique in its restrictions on who is eligible to vote: most democracies have different voting laws for citizens and noncitizens. Here, voters in all federal elections must be citizens. If you were born in the U.S., this citizenship requirement may barely cross your mind. You may glance at it as you scan the list of other eligibility requirements when registering to vote, but that’s likely the end of your concerns with proving your citizenship. However, for millions of immigrants who are on the path to citizenship, it can be a much longer process to gain the right to vote.

Unless you have gone through the process of becoming a citizen of the United States, or you know someone who has, it may seem like a simple solution for permanent residents who wish to vote. But the process is long, expensive and prohibitively challenging for many. Permanent residents first must have a green card for at least five years before they are eligible to begin pursuing citizenship. Then they must pass a series of tests to become eligible to apply for naturalization, a process which can take up to two years and cost a significant amount of money: the application fee alone is over $700. Finally, after passing an in-person interview with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, an applicant is eligible to take the oath and become a citizen. Roughly one in 10 people fail the citizenship tests. 40% of applicants must file for a fee waiver because they cannot afford the application costs. And many choose to forgo the process altogether — in 2020, there were 9.1 million green card holders eligible to apply for naturalization, and only 860,000 ended up applying.

These numbers paint a vivid picture: America is a country of immigrants, but significant portions of the population are completely barred from voting for their representatives — no matter how long they live here — unless they become citizens. States across the country have considered new bills over the last decade that would restore some voting rights to noncitizens, mostly at the municipal level or with significant restrictions attached. Cities like San Francisco and Chicago allow noncitizens who have children enrolled in the city’s public schools to vote in school board elections. The largest city to roll out significant noncitizen voting reform was College Park, Maryland in 2017, which voted to allow noncitizens to vote in municipal elections as a response to the Trump administration’s xenophobic and anti-immigrant policies.

Voting rights and access to the ballot are in no way secure for American citizens, either. Republicans across the country are hard at work rolling back access and suppressing the voices of their constituents. But this Fourth of July, take a moment to consider who the debate around voting rights often leaves out: the immigrant members of our communities who too often struggle to gain citizenship, and who are unable to have their voices reflected in their government. 100 years ago, and 100 years before that, Americans considered what it meant to be a citizen of our country, and they arrived at different conclusions. As state governments consider more proposals to extend voting rights to noncitizen residents, that definition could change once more.