Jan. 6 Was Not the Beginning or the End

A year ago, our democracy was attacked by insurrectionists seeking to block the peaceful transfer of power through a physical assault on the U.S. Capitol. Like Sept. 11, 2001, what we remember most about that day were the visible images of the attack — the storming of the Capitol, the assaults on police and the hurried evacuation of the House chamber and the Vice President.

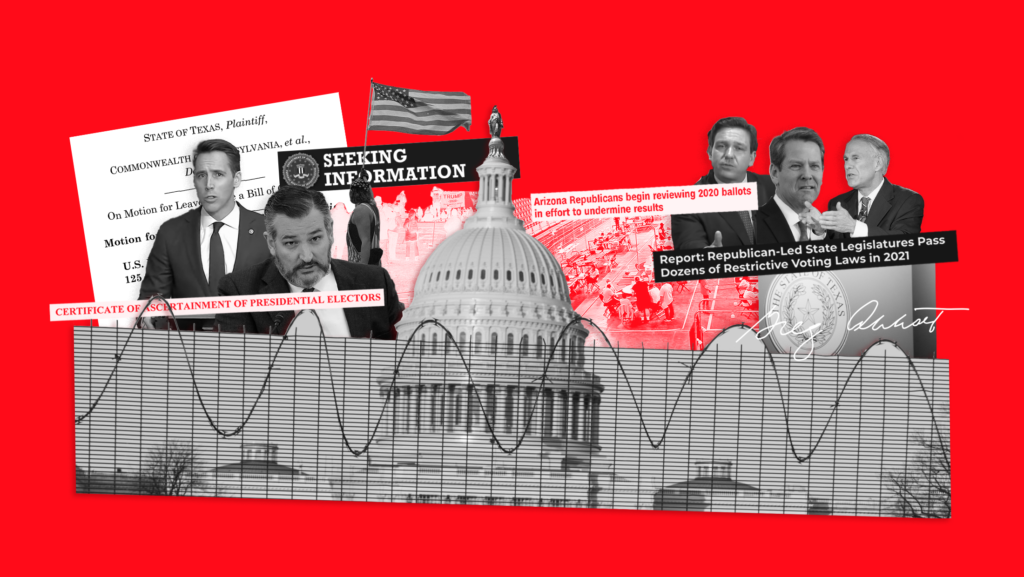

Since then, we have turned our attention to discovering the facts of that day and preventing it from happening again. First came the impeachment of Donald Trump, followed by the establishment of a select committee in Congress. We have also heard calls for tightening Capitol security, increasing the availability of the National Guard in times of crisis and reforming the Electoral Count Act.

Yet, by treating Jan. 6 as a singular event, we miss the throughline that connects this unique day to the broader set of attacks on democracy that we have seen for more than a decade and continue to witness today. If we fail to recognize the interconnection between voter suppression, election subversion and seditious insurrection, we may prevent one of them only to witness democracy’s demise at the hands of the others.

Since the election of President Obama in 2008 — indeed because of that election and the coalition he built — Republicans have been rightfully concerned that if a majority of the eligible electorate voted, the GOP would lose power. While Republicans once argued America was a center-right nation, the country’s electorate has undeniably moved to the left. In the eight presidential elections since 1992, the Republican candidate has only won 50% or more of the electorate one time. In two of the three elections that Republican presidents won since 2000, they lost the popular vote.

To offset their numerical disadvantage, the Republican Party has relied on two tools. First, it has sought to shape the composition of the electorate by making it easier for its supporters to vote, while making it harder for Democratic voters to vote. For example, when public opinion polls showed that Democrats were more concerned about the safety of in-person voting during a pandemic than were Republican voters, the GOP sought to restrict mail-in voting.

This is not new to Trump nor the pandemic. A federal court reviewing a voting law enacted by North Carolina Republicans in 2013 found that it “targeted Black voters with near surgical precision.” The evidence in that case showed that Republican state lawmakers had reviewed a variety of voting changes and then chose to restrict those methods of voting most relied upon by Black voters while leaving untouched those most relied upon by white voters.

Using the rules of voting to limit or discourage voter participation is not novel. It was used in the Jim Crow South to prevent nearly all Black citizens from voting. It was used in the 1960s to prevent young voters and members of the military from voting. And, it is being used today to prevent voters who Republicans view as likely Democratic supporters from exercising the franchise.

But that is not the only way the Republican Party can use its minority to exercise majority power. The second tool is control over what happens after the election — specifically, how votes are counted and results finalized. To use a sports analogy, if the first option is to change the rules of the game, the second is to choose the referees and umpires.

When Georgia allocated its polling places in the 2020 primary, Black voters waited in line to vote for 51 minutes and white voters waited for only six minutes —that was voter suppression. When Donald Trump asked the Georgia secretary of state to “find 11,780 votes,” that was attempted election subversion.

While that phone call may have been the most dramatic instance of election subversion, it was not the most dangerous or most common. Local officials refusing to count valid votes and county officials refusing to certify accurate vote totals are both instances of election subversion that are difficult to detect but can just as easily sway the outcome of an election.

Two aspects of Jan. 6, and the events leading up to it make it seem different — the first was the scale of physical violence at the Capitol. There is no denying the shocking images of insurrectionists as they broke through barriers, assaulted police and took to the floor of the House and Senate. I have written previously about the importance of the criminal justice system treating the people who perpetrated these crimes severely. However, for many Republicans who had been repeatedly told that voter suppression and election subversion were acceptable tactics to gain power, the escalation to violence at the Capitol was just the next step.

Equally striking about the events of Jan. 6 is the role that high-ranking government officials played in its planning. While it was no surprise that Trump led a concerted effort to undermine the 2020 election results, many political observers were shocked that the subversion efforts involved the abuse of official power, frivolous litigation and disinformation purposely spread by lawyers at the Department of Justice, White House staff and members of the Republican establishment.

Yet, the “scholars” and staff telling the vice resident to ignore his constitutional oath of office had been arguing for years that Trump’s executive power was nearly limitless. Many of the same lawyers who advanced crackpot theories in court after the 2020 election had been involved in voter suppression efforts for many years. Notably, virtually all the Republican members of Congress protesting the election results had long track records of opposing voting rights legislation and supporting restrictive voting laws.

For Republican officials panicking about losing all federal power, it was a small leap to pressure state and local election officials to disregard the accurate election results and present false returns. For their grassroots supporters, it was a tragically small step to physical violence.

Since January 2021, state legislative efforts to undermine free and fair elections have accelerated and intensified. So too have measures aimed to make election subversion easier next time.

The events of Jan. 6 were neither the end of the Trump era nor a precursor to 2024. Instead, they were the continuation of a multi-year plan for Republicans to maintain majority power with a shrinking share of popular support. Jan. 6 was neither the beginning of this crisis nor the end: it was the middle.

The best hope we have for preserving our democracy is to meet the fight where it is — in state legislatures, county election offices and in courtrooms around the country. The events of Jan. 6 may have been triggered by the timing requirements of the Electoral Count Act, but fixing one arcane law will not solve the problem we face. To win the battle for democracy, Congress must provide the legislative tools necessary. This includes laws that both prevent rigging the rules of voting and subverting the results.

Congress must pass the Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act and do so now. Otherwise, Republicans’ power-at-all-costs politics will continue and may succeed in the long run.