11th Circuit Considers Fate of Georgia Maps in High-Stakes Redistricting Case

The 11th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals will hear oral argument Thursday in a case that will determine the fate of Georgia’s congressional and state legislature maps.

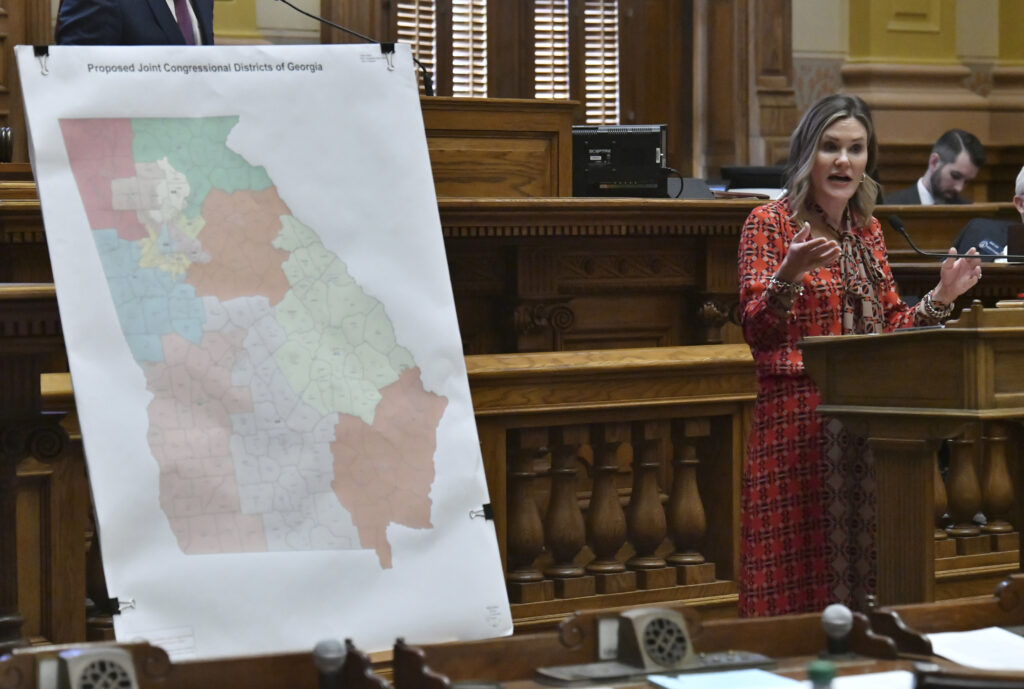

The case stems from maps enacted by the Georgia State Legislature in 2021. Voting rights advocates say the maps unfairly diluted the political power of Black communities, in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA).

Five Georgia voters filed a lawsuit against Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R) and the State Election Board in December 2021 challenging the state’s congressional map. The case was later consolidated with two other lawsuits challenging the state House and Senate maps. The plaintiffs claimed that instead of drawing new majority-Black districts to keep up with a growing Black population, the state packed some Black voters into Atlanta metro districts and cracked others among mostly white districts in more rural areas.

“Faced with Georgia’s changing demographics, the General Assembly has ensured that the growth of the state’s Black population will not translate to increased political influence,” the complaint read.

On Oct. 26, 2023, a federal judge ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and ordered the state to draw a new congressional map with an additional majority-Black district in the western suburbs of Atlanta. Georgia was also ordered to redraw the state legislative maps with seven additional majority-Black districts.

In his opinion, Judge Steve C. Jones rejected the defendants’ argument that Section 2 does not have a private right of action allowing regular citizens to file lawsuits against discriminatory maps. Defendants also unsuccessfully argued that Section 2 is unconstitutional. The judge, referencing the 2022 Allen v. Milligan decision, wrote that the Supreme Court “recently rejected the same argument urged by the State of Alabama.”

Section 2 — the most litigated provision of the VRA — has been a frequent target of the right wing in recent years. In particular, Republicans have advanced the theory that private plaintiffs cannot bring lawsuits under Section 2 in numerous circuit courts across the country. In 2023, the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that private right of action does not exist under Section 2, though the ruling only holds for states within the 8th Circuit. Raffensperger is hoping his appeal of Jones’s opinion will solidify this argument in the 11th Circuit as well.

The U.S. Department of Justice intervened in November 2023 to defend the constitutionality of Section 2 and confirm the existence of a private right of action. However, there is no guarantee that a Trump Justice Department will continue to support this argument. Without a private right of action, only the U.S. attorney general will be able to bring Section 2 cases, effectively gutting the VRA.

Beyond questioning the validity of Section 2, Raffensperger will argue Thursday that the plaintiffs failed to prove a Section 2 violation and that Section 2 is no longer relevant today. According to him, the trial court’s order to draw new majority-Black districts is unnecessary because Black candidates are successfully winning elections in Georgia and elections are driven by partisanship, not race. He denied the allegation that the original map was drawn to disadvantage Black voters, writing, “At most, Georgia enacted maps that were intended to serve various partisan goals. But if black voters suffer electoral losses because their preferred candidates are Democrats, they are in the exact same position as white voters, Asian-American voters, Latino voters, and anyone else who prefers Democrats.”

Furthermore, Raffensperger claimed that because Congress has not updated the VRA in 40 years, Section 2 should no longer be in use. In a legal brief filed with the 11th Circuit, he argued that Section 2 was a “congruent and proportional response” to “intentional discrimination by a State” in 1982. But, since Congress has not updated the law since 1982 to account for changing racial conditions, using it now to force a state to draw a race-based district would be “unconstitutional.” This argument was employed successfully back in 2013 to strike down preclearance requirements in the VRA’s Section 5.

Black voters and the Justice Department stridently defended Section 2 in their response briefs. The Justice Department wrote that “[n]either the passage of time nor the Secretary’s claims about conditions in Georgia renders Section 2 unconstitutional.” Congress is not required to continually update Reconstruction Amendment laws like the VRA. What’s more, unlike the doomed Section 5 that was only implemented in states with a history of racial discrimination, Section 2 applies everywhere. The appellees also reaffirmed the existence of a private right of action under Section 2.

As for the maps in question, they argued that there is no requirement to prove racial animus in vote dilution cases. The appellees expressed bewilderment at Raffensperger’s argument: “He would have plaintiffs prove the content of voters’ character and show, somehow, that the white majority is infected with racial animosity to a degree sufficient to explain the divergence in racial voting patterns. This approach ignores the substance of the Section 2 injury, which is not personal ill-will but structural electoral inequality.”

Each side will have 20 minutes to make their case to a three-judge panel in Atlanta. The panel consists of Clinton, Obama and Trump appointees. Oral argument will take place Jan. 23 beginning around 9:30 a.m EST.