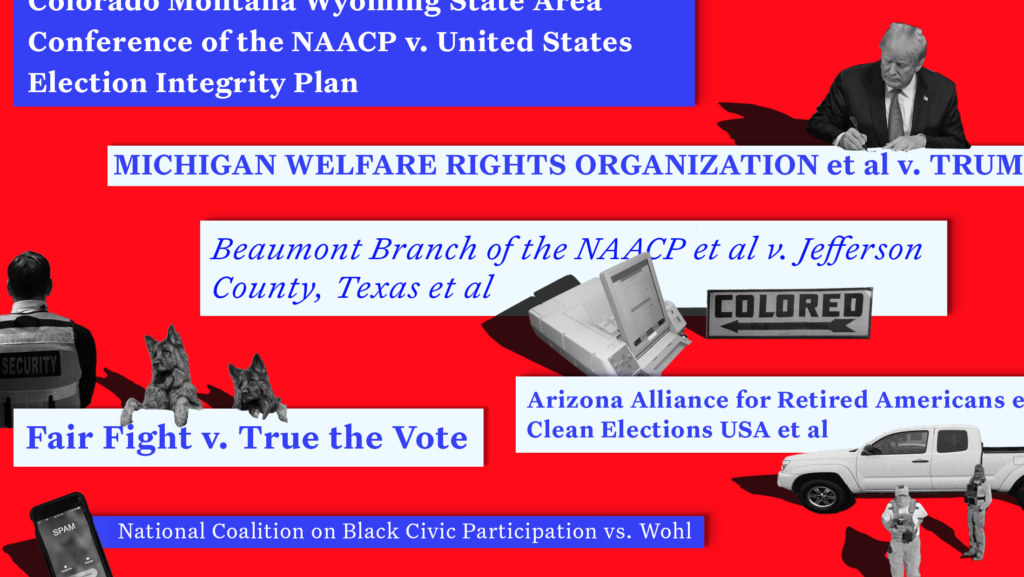

What Voter Intimidation Looks Like Today

The struggle for voting rights in the United States is marred by violence and terror, particularly for Black Americans. Since 1871, Congress has tried to curb this terror through laws safeguarding against voter intimidation and harassment, but it wasn’t until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) that such a federal law was robustly enforced.

“No person, whether acting under color of law or otherwise, shall intimidate, threaten, or coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce any person for voting or attempting to vote,” reads Section 11(b) of the VRA, a powerful legal tool used to protect against voter intimidation. Despite the country’s dark history of both individuals and groups terrorizing voters, it’s not a relic of the past. Since 2020, there have been a few high profile examples of voter intimidation in states like Arizona, Georgia, Texas and more. In each of these instances, pro-voting groups sued under Section 11(b) and litigation is ongoing in many of them.

Two right-wing activists sent 85,000 robocalls to purposefully scare voters in predominantly Black neighborhoods from voting in 2020.

In summer 2020, two right-wing conspiracy theorists, Jacob Wohl and Jack Burkman, created a robocall scheme to discourage voters from voting by mail. The thousands of calls allegedly targeted neighborhoods in Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, New York and Pennsylvania with high percentages of Black voters.

The robocaller claimed to be representing a non-existent civil rights organization called “Project 1599.” According to the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, a legal organization that sued Wohl and Burkman, the robocalls utilized a female speaker who introduced herself with a Black-sounding name. “Did you know that if you vote by mail your personal information will be part of a public database that will be used by police departments to track down old warrants and be used for credit card companies to collect outstanding debts,” the robocall said. To further intimidate Black voters who may be hesitant towards vaccines, the message continues: “The [Center for Disease Control] is even pushing to use records for mail-in voting to track people for mandatory vaccines.”

Both the Michigan and New York attorneys general got involved in lawsuits related to this scheme. Last fall, Wohl and Burkman plead guilty to telecommunications fraud in Ohio while the New York voter intimidation case and Michigan criminal case are ongoing.

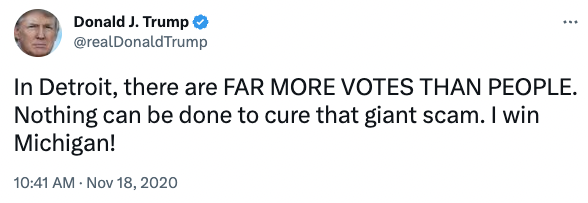

Former President Donald Trump and his campaign aggressively attempted to disqualify votes and undermine the 2020 presidential election results.

Though most Section 11(b) cases challenge behavior that intimidates voters before an election, one groundbreaking case is alleging that former President Donald Trump’s concerted effort to interfere with vote counting in predominantly Black cities after the 2020 election amounts to a Section 11(b) violation.

Two weeks after Election Day in 2020, Trump wrote: “In Detroit, there are FAR MORE VOTES THAN PEOPLE. Nothing can be done to cure that giant scam. I win Michigan!” The Trump campaign and its allies particularly focused on discarding votes in predominantly Black areas such as Atlanta, Detroit, Milwaukee and Philadelphia.

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund is challenging Trump, the Trump campaign and the Republican National Committee for their “aggressive media campaign intended to undermine the validity of the voting process, to disqualify legally cast ballots, and to shake the public’s confidence in the election results.” Aside from a federal judge rejecting Trump’s presidential immunity claims in this case, litigation is ongoing.

True the Vote challenged the eligibility of over 364,000 Georgians in the two months between the 2020 general election and 2021 U.S. Senate runoffs.

True the Vote is a right-wing “election integrity” group with well-documented voter intimidation efforts as early as 2010. The Texas-based organization set its sights on the Peach State in the short time between the 2020 general election and Georgia’s 2021 Senate runoffs.

Utilizing Georgia’s expansive voter challenge statute, True the Vote launched challenges to the eligibility of over 364,000 Georgia voters — the largest mass challenge effort in Georgia history. True the Vote assumed that individuals were unlawfully registered if they had filed a request to forward their mail to a different address in the U.S. Postal Service’s National Change of Address database. But, by using this database alone, it’s impossible to know if someone has moved from Georgia permanently or if they’re still an eligible voter who asked their mail to be forwarded for a myriad of other reasons.

Consequently, numerous eligible voters discovered that their voter registrations were at risk due to these challenges. Voters testified that they felt intimidated by True the Vote, especially when their names and home addresses were published online. One voter said that they “wonder if it is even worth trying to vote again.”

Marc and Paige discuss the major voter intimidation case against True the Vote. They break down how voter challenges work and their impact on voters.

In addition to its voter challenge efforts, True the Vote recruited “citizen watchdogs” to monitor voters and created a monetary fund to encourage vigilantes to find evidence of voter fraud. A voter intimidation lawsuit against the group has been ongoing for over two years; a court is expected to deliver a decision in the near future.

A “door-to-door campaign of voter harassment” took place in Colorado.

In 2021, a local volunteer group calling itself the United States Election Integrity Project, whose members sometimes donned official-looking badges, knocked on nearly 10,000 doors throughout Colorado. The door knockers questioned residents’ voting habits, interrogated them about fraudulent ballots and took pictures of people’s homes. Canvassers were encouraged to carry guns.

“There was no boundaries with their ethics or with civility. They will push until you give an answer. They are very intimidating,” a resident of Pueblo, Colorado told NPR after two men showed up at her door. A group of civil and voting rights organizations sued the canvasser group and litigation is ongoing.

Voter fraud vigilantes staked out Arizona drop boxes in advance of the 2022 midterm elections.

In Maricopa County, Arizona, home to Phoenix, reports of voter intimidation started to emerge soon after early voting began on Oct. 12, 2022. Over the course of a week, the Arizona secretary of state’s office referred over a half dozen instances of potential intimidation to the Arizona attorney general and the U.S. Department of Justice.

In the first reported incident, a voter was followed as they attempted to drop off their ballot at a drop box. Other reports showed vigilantes staking out drop boxes, filming voters and photographing license plates. Two armed individuals were spotted at a drop box in Mesa, Arizona.

In Arizona, these efforts were led by Clean Elections USA (funded in part by True the Vote) and an Arizona spinoff of the extremist Oathkeeper organization. The right-wing groups called upon their supporters to monitor drop boxes for “mules,” a term from the debunked “2000 Mules” propaganda movie to describe a shadowy group of individuals who collect fraudulent mail-in ballots. (In Arizona, the term “mule” also has a particularly racist tone, with the state banning community ballot collection in 2016 after a video showed an apparently Latino man lawfully returning numerous mail-in ballots. The video’s creator said he didn’t know if the man was an “illegal alien” but definitely knew he was “a thug.”)

Two lawsuits sought immediate relief to prevent the drop box vigilantes from continuing their threatening conduct during the 2022 midterm elections; a judge granted that relief.

A court stopped intimidation of Black voters at a Texas voting location a day before the 2022 midterms.

On the Monday before Election Day 2022, a Texas judge had to step in to prevent Black voters from being intimidated at a voting location in Beaumont, Texas, which serves a predominantly Black community.

A lawsuit filed by the Beaumont Chapter of the NAACP and a local voter invoked Section 11(b) and detailed the alleged intimidation: “White poll workers throughout early voting repeatedly asked in aggressive tones only Black voters and not White voters to recite, out loud within the earshot of other[s]…their addresses, even when the voter was already checked in by a poll worker, (ii) White poll workers and White poll watchers followed Black voters and in some cases their Black voter assistants around the polling place…and (iii) White poll workers helped White voters scan their voted ballots into voting machines but did not similarly help Black voters scan their ballots.” The judge prohibited election officials, workers or volunteers from engaging in these actions.

As exemplified by the lawsuit in Beaumont, Texas, federal protections against intimidation are an important tool to protect voters in emergency situations. However, with many cases still ongoing, the outcome of lawsuits challenging long-term efforts that implicate Trump, True the Vote and other right-wing groups remain relatively untested in courts. No matter the result, the 2020 and 2022 elections have proved that voter intimidation is still alive and well across the country.