The Racist Roots of Runoffs in the South

On Nov. 3, 2020, voters in Georgia went to the polls and cast their ballots in two separate U.S. Senate races. Once all the votes were counted in both elections, the numbers showed incumbent Sen. David Perdue (R) ahead of now-Sen. Jon Ossoff (D) and Rev. Raphael Warnock (D) ahead of then-Sen. Kelly Loeffler (R). In most states, that would’ve been the end of it, but, as we know, the Senate elections in Georgia didn’t end there. Since neither candidate received a majority of the vote on Election Day, state law required a runoff between the top two candidates. When Georgia held the runoff on Jan. 5, 2021, Sen. Warnock secured a majority of the vote and Sen. Jon Ossoff (D) defeated Perdue, giving Democrats wins in both elections and flipping partisan control of the U.S. Senate.

While all eyes were on the Georgia Senate runoffs early last year, the Peach State’s electoral system is part of a broader trend of runoff elections throughout the South, usually in primary elections. Texas, for instance, held two primary elections this year — a first round on March 1 and a runoff on May 24 for races where no candidate received a majority of the vote. But what may seem like a quirk of election law actually has darker origins. Throughout the South, the use of runoffs in primary elections is a legacy of the Jim Crow era, when white supremacists used every tool they had available — including election rules — to maintain their hold on power.

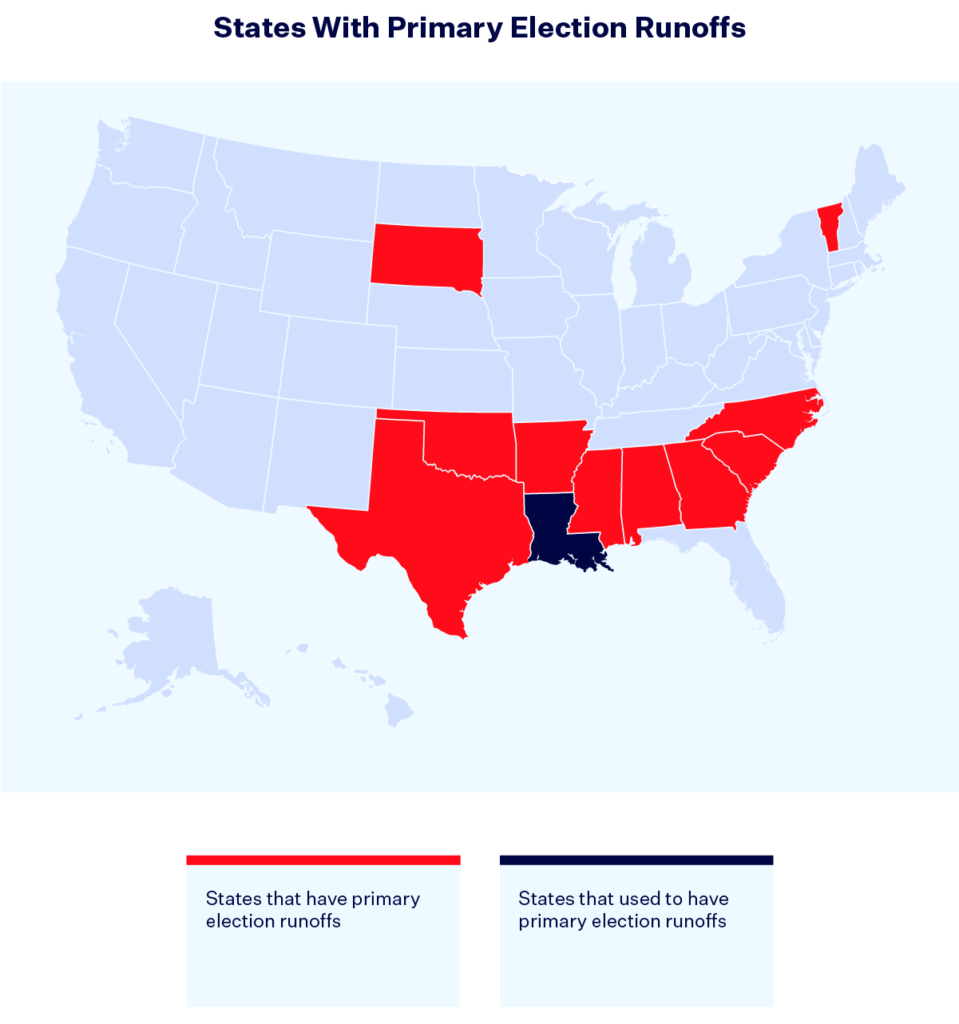

Ten states use runoffs in primary elections.

Besides Georgia and Texas, eight other states — almost all of them in the South — use runoffs in partisan primary elections. Like Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Texas all require candidates to win a majority (meaning over 50%) of the vote. In North Carolina, candidates only need 30% of the vote to avoid a runoff. Louisiana also had primary runoffs until it adopted the unique “jungle primary” system in the 1970s. Of these ten states, Georgia is the only one that also holds runoffs for general elections.

South Dakota and Vermont are the only two non-Southern states to use primary runoffs. In South Dakota, a runoff only occurs if at least three candidates are running and no candidate wins 35% of the vote. In Vermont, a runoff only occurs if there is an exact tie between the candidates. In both of these states, these rules are almost never applied and have a much smaller political effect than they do in their Southern counterparts. Furthermore, the circumstances that led Southern states to adopt runoffs were very different.

Southern states adopted primary runoffs to help maintain white Democratic control of politics.

In the Jim Crow South, white supremacists and segregationists manipulated electoral rules to ensure their continued dominance. Primary runoffs were one part of this. At the time, the Republican Party was virtually nonexistent in the South, so winning the Democratic primary was tantamount to winning the election. Having a runoff during the primary ensured that a candidate supported by the anti-civil rights majority would prevail.

As more and more Black Americans became voters in the South, the runoff system also helped to ensure they were excluded from exercising real political power. Under racially polarized voting — meaning voters of different races largely support different candidates — runoffs gave white voters a chance to defeat candidates supported by Black voters. Under a plurality system — where you just need the most votes to win, not necessarily a majority — candidates supported by Black voters could only win their primaries if the white vote was split between several candidates. By requiring a candidate to win a majority of the vote, however, the runoff system allowed white voters to consolidate around a single candidate to defeat the candidate supported by Black voters. Even as other aspects of Jim Crow were dismantled, the primary runoff system served to maintain the power of white Americans.

Georgia adopted runoffs after a previous electoral system that favored white voters was overturned.

Beginning in 1917, Georgia used something called the county unit system in primary elections, which operated sort of like a state-level electoral college. Under this system, each of Georgia’s 159 counties was classified as urban, town or rural. In statewide primaries, like for governor, urban counties received six “unit votes,” town counties received four and rural counties received two. A candidate who won a plurality of votes in a county received all of that county’s “unit votes.” Since Georgia’s minority communities were concentrated in urban counties, and white voters were spread throughout rural counties, this system allowed rural counties to prevail against their urban counterparts, thereby giving outsize electoral power to white voters in the Peach State.

In 1963, the U.S. Supreme Court declared the county unit system was unconstitutional for violating the “one person, one vote” principle articulated the prior year in Baker v. Carr. In response, Georgia legislators set about devising new ways to maintain white political power. State representative Denmark Groover (D) advocated adopting runoffs for all Georgia elections as a replacement for the county unit system, stating on the Georgia House floor that “we have got to go to the majority vote because all we have to have is a plurality and the Negroes and the pressure groups and special interests are going to manipulate this State and take charge if we don’t go for the majority vote.” His proposal was adopted as part of the state’s election reform package passed in 1964.

In the 1990s, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) filed a lawsuit against Georgia’s primary runoff system, arguing the system violated the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) by diluting the voting strength of Black Georgians. The DOJ identified 35 Georgia elections where Black candidates received a plurality of votes in the first round of a primary but lost their runoffs when white voters coalesced around their opponent. The DOJ’s lawsuit was eventually consolidated with Brooks v. Miller, a challenge brought by a group of Black voters. In 1998, although the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals concluded the runoff system didn’t violate the VRA, it nevertheless agreed that “the virus of race-consciousness was in the air” when it was adopted.

When it comes to elections, context matters.

While it’s clear that the existence of the primary runoff system throughout much of the former confederacy owes its origins to racism, that doesn’t mean that runoff elections themselves — or the similar voting systems used in California, Washington and Maine — are inherently racist. It’s the context of the South at the time — a region dominated by a single political party and characterized by racially polarized voting — that made primary runoffs a tool of white supremacy. Any seemingly neutral election practice can become problematic depending on the real-world circumstances in which it’s used.

That’s why the VRA and other voting laws call for evaluating the “totality of the circumstances” when deciding if an electoral practice has a discriminatory effect or a disparate impact on some group of voters. It’s not enough for a voter ID requirement or the placement of polling locations to appear facially neutral. You have to dig a little deeper and understand how it operates in the real world to really determine if an electoral practice or rule can be used to deny people their right to vote.