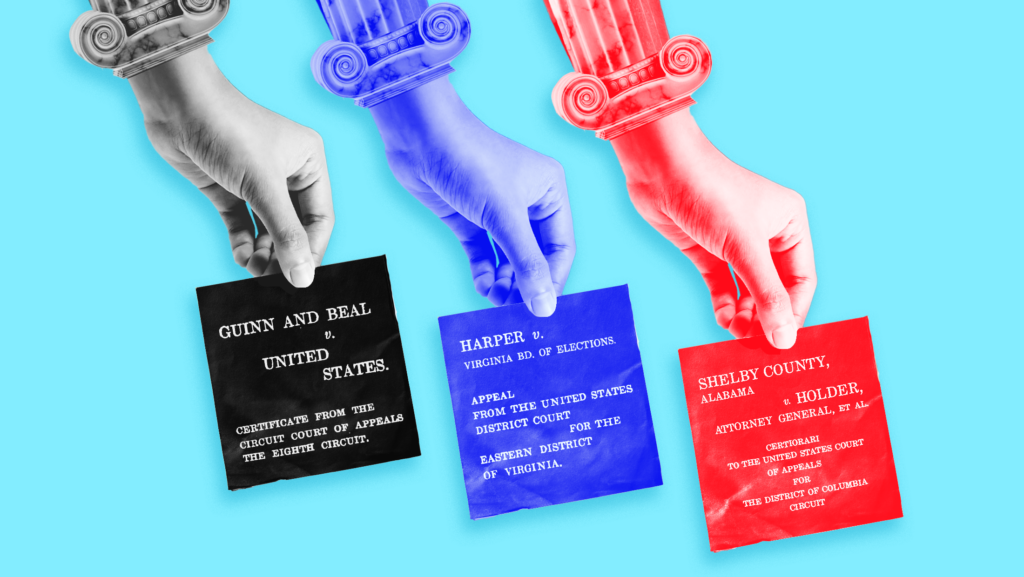

Ten Voting Rights Cases That Shaped History

All eyes are on the U.S. Supreme Court. As we await the confirmation of a new, history-making justice, we’re turning back the clock and reviewing crucial voting rights cases decided by the Supreme Court.

If you missed it, make sure to read “Nine Redistricting Cases That Shaped History” where we cover landmark gerrymandering and vote dilution cases, often challenged under the same Voting Rights Act provisions or constitutional amendments that we see in these cases.

From 1876 to 2021, we saw the rise (and recent decline) in court protection for voting rights — here are 10 cases that shaped history.

1. United States v. Reese (1876)

“The statute contemplates a most important change in the election laws… This is a radical change in the practice, and the statute which creates it should be explicit in its terms. Nothing should be left to construction, if it can be avoided. The law ought not to be in such a condition that the elector may act upon one idea of its meaning, and the inspector upon another.”

The case: In the first voting rights case since the passage of the 15th Amendment, two elections officials in Tennessee refused to allow a Black man to vote. The elections officials were sued for violating the Enforcement Act of 1870 (a federal law which, among other provisions, outlined penalties for interfering with the 15th Amendment’s guarantee of voting rights). The Supreme Court held that the relevant sections of the Enforcement Act were unconstitutional because they were not sufficiently tailored to enforce the 15th Amendment.

The significance: In addition to dismantling a crucial enforcement mechanism for voting rights, the Court held that the 15th Amendment “does not confer the right of suffrage upon any one” but instead prohibits disenfranchisement on account of race. This narrowly construed reading of the 15th Amendment had devastating effects: southern states began passing laws that were facially neutral, but were clearly designed to disenfranchise Black voters. For years after United States v. Reese, poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses and other nefarious voting rules were upheld against legal challenges because they technically applied to all voters.

2. Guinn v. United States (1915)

“It is true it contains no express words of an exclusion from the standard which it establishes of any person on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude prohibited by the Fifteenth Amendment, but the standard itself inherently brings that result into existence, since it is based purely upon a period of time before the enactment of the Fifteenth Amendment, and makes that period the controlling and dominant test of the right of suffrage.”

The case: Oklahoma’s literacy test had an exemption for individuals and their descendants who could vote on Jan. 1, 1866 (prior to the 15th Amendment), were citizens of a foreign nation or had served as soldiers prior to 1866. This exemption, known as the grandfather clause, effectively permitted illiterate white citizens to vote, while continuing to bar Black voters whose parents or grandparents had been enslaved before 1866. The Supreme Court saw through Oklahoma’s scheme and struck down the state’s grandfather clause for violating the 15th Amendment.

The significance: In striking down grandfather clauses (though not literacy tests themselves), this ruling illustrated the potential for courts to stand against racial discrimination. However, most states continued to create disenfranchising laws and tailored them to evade judicial review.

Fun fact: Guinn was the first case where the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) filed a brief, helping to launch the organization into prominence.

3. Smith v. Allwright (1944)

“A right to participate in the choice of elected officials without restriction by any state because of race… is not to be nullified by a state through casting its electoral process in a form which permits a private organization to practice racial discrimination in the election. Constitutional rights would be of little value if they could be thus indirectly denied.”

The case: The Texas Democratic Party prohibited Black individuals from voting in its primaries, and the state of Texas argued that this was permissible because it was not state action. The Supreme Court disagreed, holding that the party’s white-only primaries violated the 14th and 15th Amendments.

The significance: The ruling overruled a decision made nine years prior which permitted white-only primaries on the basis that they were run by private, voluntary organizations. However, the court held in Smith that Texas delegated its authority to the state Democratic Party and thus the unconstitutional discrimination was, by extension, state action. The end to the white-only primary was an important step for building Black political power in the South and the ruling also solidified the idea that public activities, such as elections, can be subject to constitutional review even if they are managed by a private organization.

4. South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966)

“After enduring nearly a century of widespread resistance to the Fifteenth Amendment, Congress has marshalled an array of potent weapons against the evil, with authority in the Attorney General to employ them effectively.”

The case: Section 5 of the recently enacted Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 subjected states or counties with histories of voter suppression to pre-approval before enacting new election law changes. South Carolina challenged the constitutionality of the VRA, arguing that the Section 4 formula (which determined which jurisdictions were covered by Section 5’s pre-approval process) violated the principle of equality between states and denied them due process. The Supreme Court held that the 15th Amendment was a valid constitutional basis for the VRA and the challenged provisions.

The significance: This ruling upheld the heart of the VRA. For decades, the preclearance requirements were an effective tool in proactively preventing states from enacting discriminatory voting laws.

5. Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections (1966)

“Voter qualifications have no relation to wealth nor to paying or not paying this or any other tax.”

The case: A Virginia resident who was unable to pay the $1.50 poll tax to vote challenged the law under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The Supreme Court overruled a 1937 decision to find Virginia’s poll tax unconstitutional.

The significance: The 24th Amendment, adopted in 1964, prohibited poll taxes in federal elections but five states, including Virginia, continued to impose poll taxes to vote in state elections. Consequently, the majority decision was not rooted in any changes in the Constitution’s text (at the critique of Justice Hugo Black in his dissent), but rather a recognition of changing times and a crucial ruling that expounded upon the concept of equal opportunity to vote.

6. Richardson v. Ramierez (1974)

“The understanding of those who adopted the Fourteenth Amendment, as reflected in the express language of § 2 and in the historical and judicial interpretation of the Amendment’s applicability to state laws disenfranchising felons, is of controlling significance in distinguishing such laws from those other state limitations on the franchise.”

The case: Three individuals, all of whom had finished their sentences for felony convictions and still were not allowed to register to vote, challenged California’s felony disenfranchisement provisions under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. In reversing the decision of the California Supreme Court, the U.S. Supreme Court found that California’s felony disenfranchisement laws do not violate the Equal Protection Clause. In support, the Court pointed to Section 2 of the 14th Amendment, which forbids the abridgment of voting rights “except for participation in rebellion, or other crime.”

The significance: The Richardson decision made clear the constitutionality of felony disenfranchisement as an overarching concept, but left open the possibility for certain laws to be challenged on the basis of unequal enforcement or racially discriminatory intent. Since Richardson, advocates have also challenged felony disenfranchisement under Section 2 of the VRA, but the Supreme Court has not taken up these cases. As of 2020, an estimated 5.2 million Americans are stripped of their voting rights because of a current or prior felony conviction.

7. City of Mobile v. Bolden (1980)

“To prove such a purpose, it is not enough to show that the group allegedly discriminated against has not elected representatives in proportion to its numbers… A plaintiff must prove that the disputed plan was ‘conceived or operated as [a] purposeful devic[e] to further racial . . . discrimination.’”

The case: A class action lawsuit on behalf of all Black voters in Mobile, Alabama was brought to challenge the city’s practice of at-large elections of city commissioners. They argued that the at-large elections diluted the voting strength of Black citizens in violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments and Section 2 of the VRA. The Supreme Court rejected this argument, holding that the 15th Amendment did not guarantee the right to elect candidates of choice. The Court also upheld multimember districts as constitutional after holding that facially neutral actions were unconstitutional only if motivated by discriminatory purposes.

The significance: When enacted in 1965, the outer bounds of Section 2 of the VRA were undefined. In Bolden, the plurality opinion held that Section 2 does not afford any additional protections beyond the 15th Amendment. Just two years later, Congress amended the VRA, changing the language in Section 2 to include that it is unlawful for the “results” of a voting process to abridge the right to vote. This created the possibility to challenge laws that had a discriminatory impact, even without proving an intent to discriminate.

8. Crawford v. Marion County Election Board (2008)

“The State has identified several state interests that arguably justify the burdens that [the voter ID law] imposes on voters and potential voters… Each is unquestionably relevant to the State’s interest in protecting the integrity and reliability of the electoral process.”

The case: In 2005, Indiana passed a law requiring citizens voting in person to show government-issued photo ID, the first strict voter ID law in the nation. The law was challenged for unduly burdening the right to vote in violation of the 14th Amendment. In contrast, the defendants argued that the law was necessary to prevent voter impersonation at the polls. The Supreme Court affirmed the decision of the lower courts, voting 6-3 to uphold the voter ID law because the state’s interest in preventing voter fraud justified any burdens placed on voters.

The significance: A year later, the law was actually struck down in state court for violating the Indiana Constitution. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court’s ruling allowed state interests (even those not based on evidence) to outweigh the burdens on voters derived from a universally applicable law. In turn, this paved the way for a proliferation of strict voter ID laws across the country and validated the GOP’s embrace of “voter fraud” to justify new restrictions.

9. Shelby County v. Holder (2013)

“In 1965, the States could be divided into two groups: those with a recent history of voting tests and low voter registration and turnout, and those without those characteristics. Congress based its coverage formula on that distinction. Today the Nation is no longer divided along those lines, yet the Voting Rights Act continues to treat it as if it were.”

The case: Shelby County, Alabama, a jurisdiction covered by Section 5 of the VRA, argued that the Section 4 formula was unconstitutional. When appealed to the Supreme Court, a 5-4 majority ruled that the Section 4 formula was outdated and thus an unconstitutional burden on states, effectively gutting Section 5.

The significance: This ruling struck down one of the VRA’s most powerful tools and states began an almost immediate push for new restrictive voting measures. In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts expressed his expectation for Congress to update the formula, thus reviving the preclearance process. Congress has failed to do so.

Read our previous coverage on Shelby County here.

10. Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee (2021)

“But the mere fact there is some disparity in impact does not necessarily mean that a system is not equally open or that it does not give everyone an equal opportunity to vote.”

The case: Several Democratic groups challenged two Arizona voting laws (one that criminalized ballot collection and another that required ballots cast in the wrong precinct to be rejected) for violating Section 2 of the VRA. The full 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the plaintiffs and struck down both regulations. However, the Supreme Court overturned this decision, finding that the two laws did not violate Section 2.

The significance: For Section 2 claims, a court considers whether a law was enacted with a discriminatory purpose or has a discriminatory impact (also known as the intent test and results test, respectively). In the Brnovich opinion, Justice Samuel Alito declined to establish a formal test, but provided a list of five “guideposts” to help determine if a law has a discriminatory result, thus diminishing the power of the provision and the ability to successfully bring claims of discriminatory voting rules under Section 2.